Steve Pulaski

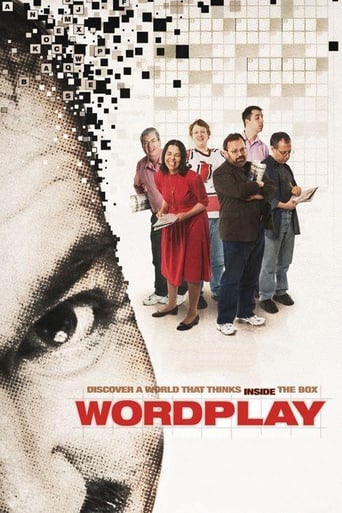

My seventy-six-year-old grandmother has two rituals she's carried with her every day for the past twentysomething years - first thing in the morning, upon walking outside in the bitter cold or the scorching Chicago humidity to get her newspaper, she'll always do the crossword puzzle and she'll always watch the new episode of Jeopardy! in the afternoon. I remember observing her as a young child, staying overnight at her house, wondering how she could fill in the blanks to a complex puzzle so quickly or respond so confidently to nearly every question on the gameshow. To this day, her energy levels and intelligence far surpass mine and I'd be damned if she wasn't one of the wisest people I've come to know.According to Will Shortz, the editor of the crossword puzzles found in The New York Times, she would fall into one of two categories of people who are good at crossword puzzles. Those two kinds of people are musicians and math-minded people, otherwise known as those who excel at actuary sciences, accounting, or problem solving of any kind. These kinds of people are said to process a great deal of coded information in their field, allowing them to have more of an aptitude at trying to decode your average crossword puzzle found in your local newspaper.Wordplay is a documentary about the crossword puzzle, a national passtime of sorts that compliments Sunday morning like a piping hot coffee or a freshly baked doughnut. Throughout the film, we observe a national crossword competition, where dozens of people from around the world gather to solve a series of crossword puzzles in record time, whilst documentarian Patrick Creadon profiles a select few individuals from the competition to give us insight on the difficult nature of crossword puzzle solving and creating.One of the contestants in the the national competition is Trip Payne, a puzzlemaker who has crafted an upwards of 4,000 unique crossword puzzles and frequently competes on a national scale. Armed with the support of his husband and his consistent desire to outdo his previous performance, Payne makes his way through the national competition in order to win the title of the crossword champion.Another individual Creadon profiles is Merl Reagle, a crossword puzzle maker who shares his insights on how to make a fun and challenging puzzle. Reagle, similar to Shortz, always starts with a core idea, for example, "Word Play," where all the subsequent words, be them up, down, or across, will have the word "word" or "play" embedded somewhere in them but not deal directly with either of those words. Reagle sits as his dining-room table for hours, crafting a puzzle, sometimes surprising himself with how many words he knows. These scenes are the most intimate and revealing, mostly because we see how something we either take for granted or don't pay much thought to is structured. Just the thought of trying to create a crossword puzzle, let alone solve one, for me, makes me nauseous; I struggled to make word searches in grade school.Creadon also holds interviews with people like Jon Stewart, a lover - perhaps connoisseur - of Shortz's crossword puzzles and Bill Clinton, all of whom enjoy challenging themselves and testing their verbosity with The New York Times puzzle. A terrific scene comes about halfway through the documentary, where we see Stewart, Clinton, and other celebrities try to solve one of Shortz's crossword puzzles in record time. "I'm so confident in myself," Stewart claims, "I'm going to do it in gluestick." Wordplay, much like toying around with the English language, is a lot of fun. The heart of the documentary is in the characters it profiles, specifically people like Payne and Reagle, who craft these complex crossword puzzles. When the documentary takes the last twenty-five minutes to profile the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, the spark of charisma in the film greatly simmers. The people Creadon focuses on are so filled with insight and ideas that it almost seems criminal to shift focus late in the game when we have a wealth of ideas and language trickery being detailed right before us.Directed by: Patrick Creadon.

evening1

This mildly diverting documentary shows that even bookish people who get their workouts sharpening pencils (with erasers, of course) can participate in a sporting event.It's the annual competition of crossword puzzlers, founded by Will Shortz, puzzle editor of the New York Times and a personality on NPR.Judging by this film, puzzlers tend to be non-flashy, male, articulate, self-deprecating, and just as competitive as your average ball player or hoop dunker.I was surprised to see that puzzling has become a spectator sport. This film proves it by showing a pair of top-ranked, ear-plugged puzzlers battling it out on wall-sized grids as experts broadcast commentary to a hotel ballroom full of onlookers.Though a variety of hip afficionadoes are interviewed on their avocation -- folks like Jon Stewart and Bill Clinton -- it's implied here that most puzzlers are fairly nerdy. One top contender was shown at home with his male lover, but little is said generally about these players' private lives. Which leaves one wondering a bit about the rest of the story, since so many of these enthusiasts are hyper wordy. With this exquisite sensitivity, one wonders if and how they "click" with non-wordsters outside of this rarefied fold.

dmturner

As I watched this movie, I heard all around me little appreciative chuckles from the audience. I like but don't love crossword puzzles (my mother did the double crostics when I was a kid, which were beyond me) and can take them or leave them, but Will Shortz is a gem and the theme of competition is universal. Heck, I don't usually even like documentaries, but I felt as if this funny, courteous, kind, assortment of people was inviting me into a particularly enjoyable party in which nobody was a wallflower. The film-makers deserve credit for the humor and kindness of this film, as well as for the excellent craftsmanship (and their interesting assortment of celebrity interviewees)