flavia_r_ida

I'm a white European-American female. The closest thing I have to compare to the Koori of Australia are Native Americans. In "The Last of the Mohicans", the male protagonist dies because he falls in love with a white female. In this movie, the Koori boy dies because he falls in love with a white female. I find this disturbing, on more levels than one. The girl in this movie doesn't understand the Koori boy is courting her, and that frightens her, and that dismays the boy. So far understandable. But you want me to believe that a Koori male of that caliber would kill himself because some white female doesn't want him? What a waste of a great character.

frankwiener

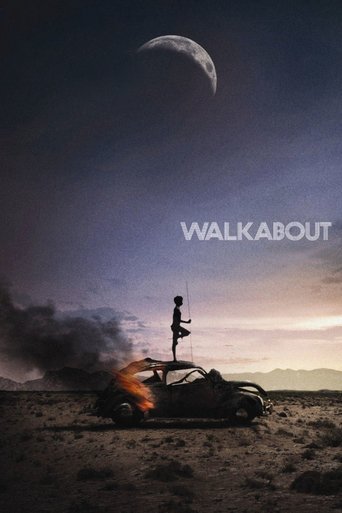

Although this film is often visually beautiful, it also depicts a very bleak world in which the thin mask of "civilization" fails to disguise our most fundamental roots in the raw, natural world that exists beyond the skyscrapers and modern conveniences of urban life. It is a world filled with devouring insects, menacing reptiles, foreboding skeletons, and, perhaps worst of all, the mental fragility of humans that can so easily create horrific outcomes.Aside from its broader, more universal theme, the film also reveals the stark contrast between the cities of Australia, where the overwhelming majority of people live, and the vast, enormous wilderness that covers most of that magnificent nation and continent.This is a very important film that has managed to overcome its undeniable 1970's cultural attributes. To me those aspects of the film's era are superficial in comparison to its profound message concerning our very existence as a species that happens to control this planet, a tiny speck within an endless universe that is far beyond our control.The names of the three main characters are never revealed, as if they have no personal identity as individuals. While their different races and ethnocultural backgrounds are essential on one level, the specific details of their individual lives are insignificant on another, higher level. They are human beings. Beyond that, they are just another species, granted a very influential species within its limited realm, in a universe that is much more powerful and that renders all of the particular aspects of their lives, including their names, meaningless.I am surprised that some other reviewers had problems with Jennie Agutter's nude scenes as they include no sexual activity whatsoever. In my view, the appearance of a beautiful young woman in her natural state is deliberately used to offset all of the ugly aspects of the world that exist around her and that threatened her physical loveliness from every direction. Even her own father, of all people, came very close to eliminating her forever. For me, her natural beauty serves as a triumph over the hideousness, even horror, that prevails around us and that threatens us every day. She is beautiful. The scenes are exhilarating as art. Regardless of how old her character is supposed to be, she looks like a fully grown woman to me.I don't know if animals were actually killed as a result of the production only because the standard US disclaimer from an American animal welfare organization does not appear among the final credits. If animals were killed only for the making of a movie, I would be very disappointed, especially since the killing would have been completely unnecessary.In spite of the sometimes disturbing nature of our world, the three young people at the center of the film do manage to achieve, under very difficult circumstances, an idyllic paradise, even if it is of very brief duration. As the film reminds its viewers again and again, our individual lives in the general scheme are a mere flash in time, whether we choose to accept this reality or not.The final quote from A.E. Housman's nostalgic poem "A Shropshire Lad" illuminates the situation best: "That is the land of lost content, I see it shining plain, the happy highways where I went, And cannot come again." Tragically, the central characters cannot return to those fleeting moments of heavenly bliss that they shared in the wilderness. In this imperfect world, we must seize perfection as it occurs because we may never live to experience it again.

sharky_55

If a nature documentary Attenborough style chooses the choicest shots, the majestic voice-over and score to elicit maximum excitement and wonder, Roeg's Walkabout does the opposite. It does not seek to amaze, but present an unflinching look at the Australian outback, where at any time you could be hundreds of kilometres from the nearest petrol station. Roeg shoots with a tenacity for the fauna and flora; horny lizards bathe in the ember sun, wombats prod at sleeping children, ant and flies are ever constant. The temptation to err and fleetingly capture Uluru in all its size and iconicity is rejected. He will zoom into a random incident of an animal devouring another, giving it no symbolic power but simply showcasing the harshness for what it is. And then he will zoom out from our characters, contextualising them and making them tiny amongst the crimson red hills of sand. Barry's score, with its cacophony of bleeps, high pitched shrieks, radio static and echidna paws trampling up dust, adds a hallucinogenic mood and makes the great stretches of land vast and infused with a haunting beauty. The trees respond to this and seem to shiver in the hot wind. Sometimes, he will forgo hard cuts and dissolve cliffs and mountains and other scenery against each other, as if to represent passing of time. But he never puts a definite marker on these periods; a crucial element of the story is the vagueness of this perception, as the pair wander confused, lost and desperate. Prior to this wandering, there is a wordless intro of sorts, where we survey the image of modernity in 70s Adelaide, but against the backing of a didgeridoo. Roeg is selective about inserting hints of this world with our main narrative. As our nameless Aboriginal boy on his walkabout hunts and skins a kangaroo, we crosscut over to a butcher who mimics the same actions; who tears at tendons with his hands rather than his teeth, but the intent is the same. Dangling and playing around trees is compared to a group of Indigenous women having their fun in the now burnt husk of the car. And in one moment where the two collide, and Barry's score kicks into a haunting gear, and we freeze-frame on animals escaping and reverse this again and again. But I do think in this instance it is a tiny bit over dramatic - it may be in little Luc's perspective, but is the objective of hunting quite so different? And then there is something which they both share, because it is the inescapable nature of humans. Jenny Agutter was 17 by the time that filming began and it was even more appropriate, as she neared adulthood. She has to continually reign in his younger brother, whom is oblivious to the situation, as well as deal with her developing sexuality. The sensual glances from the Aboriginal boy (and I think from the father too at the beginning, very subtly, who has recognised her physical growth) mirror those of the weather scientists towards their female colleague. Two teenagers will share glances at sensually formed branches in the dark, and as she explores the ruins of an old shack and the burial mounds of the inhabitants, he ha a wide grin on his face as he looks over. Roeg intercuts this with a extreme closeup of a termite burrowing its way out of the dirt ground, as if trying to form a conscious connection between the two worlds, but it is in vain. Likewise, when he performs a ritualistic mating dance, with clay smeared body paints, she shys away because she does not understand. But in some ways, in the stripped dialogue between the siblings, she does know a little. She is embarrassed of her nudity and hurries to clothe herself as he dances to the didgeridoo, but earlier, she is much more at ease twisting and sliding her way through the crystal clear pool, and there is almost a conscious sense of display at work. She understands a little then, but does not fully grasp this experience, even as Roeg fast forwards and presents us again with the image of modernity, inside that identical dainty little kitchen for the housewife. And we dissolve again, and she flashes back to that idyllic time in the pools. It is a remarkable achievement to make a film so balanced, so unbiased, so thoughtful of both sides - Roeg does not attempt to fetishsize the mystic power and authentic natural living of the Aboriginals in the outback, and there is no reward for the pursuit of it after throwing away the cityscape life. The boy is resourceful, but not in a wondrous way. The modern citizens are not caricatures for the way of harsh contrast (except perhaps for one fleeting moment at a plantation). And Roeg, having done this in 1971, as a British director, has a remarkable sensibility for the cultures involved, even as Aboriginal racial tensions waver today. The final scene is poetic powerful and completely devoid of any cultural, racial or sexual prejudice. But it becomes lost in time and memory. It is a dream, after all.

knucklebreather

Much has been written about the cinematography of "Walkabout" and it's certainly a beautiful film, with amazing visuals of nature in the Australian outback, but also contrasting shots of the built environment of modern civilization. Certainly anyone interested in a visually stunning film should check this out and few will be disappointed.Looking at it as a broader film, it's still very interesting. The story of a brother and sister abandoned in the Australian outback and surviving with the help of an Aboriginal teenager, it feels like an experimental film at times but has a coherent and easy to follow story at its heart. I chose to interpret it as a pretty straightforward story about humans rejecting their simple roots as hunter/gatherers to live in the built, civilized world where meat comes from the butcher, and the regret at having made that trade off, at having given up Eden to live tediously in the city. The film certainly lays on this sort of symbolism heavily. This sort of story might be enlightening if I hadn't seen and read it so many times before, but nevertheless it was done powerfully here and provided me with something to think about.