jamesmartin1995

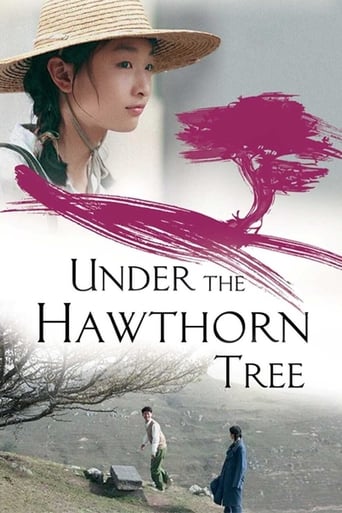

There is a scene, about two thirds of the way through, in which an older woman, mother to three children, sits down with her eldest daughter and the boy she has fallen in love with, and for about five minutes, they speak to each other. These are hard times – all three know it. At the beginning of the scene, the mother is sceptical. She treats the two as children, with their heads in the clouds. But the conversation develops, and gradually, we realise a change in the mother. She cannot back down – in practical, surviving terms, she is in the right. But she softens her approach, and by the end, even has a kind of basic respect for the two, behind her frosty exterior. For she has seen the love that these two have for each other, and recognised it. It was then that I knew I was watching a great movie…If 'Lola' was a disappointment in the Asia Triennial Film Festival this year, Zhang Yimou's new film – a love story set during the Chinese Cultural Revolution – makes up for it tenfold. It's not very often I get the opportunity to rave about a film like this, as they are so rarely done well; cynicism, plot complication and saccharine cliché at turns are what often makes a love story such as this horrifically superficial and painful to watch. But Yimou knows what he is doing. Arguably the finest working Chinese director (with the masterpieces 'Raise The Red Lantern', 'Hero' and 'House of Flying Daggers' to his name), he has succeeded here in making a beautiful, heartfelt film, spilling over with the love and care that has gone into its production. Zhang Jingqiu is a student sent to do research and write a report for her school on a small village in Yichang City. She stays with the head of the village and his family. While there, she meets Sun, a geology student. What follows is inevitable. But how delicately rendered it is: Jing is the most beautiful, innocent young woman Sun has ever seen, and Jing, emotional and vulnerable, is amazed by him. Love at first sight! But this isn't as whimsical as it sounds. Yimou hasn't completely forgotten his political ideals and ability for scathing criticism: with this latest endeavour, he explores just how stifled and suffocating Mao's regime was for everyone under his power, and the emotional deadlock that threaten to destroy his protagonists at every turn. Frolicking, even in the most innocent sense of the work, was risky; Sun and Jing are from different classes, exacerbating the issue. Were they to be found out, her life and ambitions to work as a teacher would be ruined.I was unsure, during the first half of the film, what to think. Yimou makes some interesting structural choices as regarding his narrative – many of the scenes are divided by inter-titles, telling us of an event we are not allowed to see, and then moving on to its aftermath. Most directors would die before doing this – especially in a film requiring the emotional impact this needs – and, I admit, I doubted its benefits at first. But instead of hindering the drive of the plot, Yimou has used it in such a way – not to cut the film into a digestible running length, but simply to avoid over melodramatics, and focus (almost entirely) on the couple in question. Supplementary information is given to us by other means – the filmed scenes are belong exclusively to Yimou's exploration of our two protagonists' relationship. It works perfectly. Of course, we all know the rules. Both lovers are alive at the beginning; the same cannot be said after the end credits begin to roll. What makes this movie so wonderful isn't its startling originality; it isn't going to revolutionise cinema as we know it, or spark off long lasting controversy. Rather, what we are offered is a little less prestigious, but by no means less special. What we find is emotional honesty – when we start to cry at the end, we don't feel cheated; instead, we revel in the director's success. More importantly, though, we have felt for his characters, having engaged with them completely, and have a kind of renewed respect for the kind of pure, unconditional love we have been shown. The film is yet another example of Yimou's mastery of the 'anti-melodrama' – much like his early work, this is incredibly restrained, beautifully measured and patiently observed, shot through with a warmth and tender humanity that shouldn't inspire anything but admiration. Cynics – stay away. But for all the romantics out there (of which I, admittedly, am one), I couldn't recommend this more highly. Simply put, it's exquisite.

Ruben Mooijman

In some restaurants, the chef goes out of his way to create complex dishes, with intricate combinations of tastes, colours and cooking styles. Others specialize in simple dishes, that stand out because of the quality of the ingredients. A simple pasta pesto can be a treat if it's made with the best olive oil, freshly grated parmesan and homegrown basil. Under the Hawthorn Tree is like such a simple, but delicious dish. It's a straightforward story of a forbidden love, told in a basic way, without many frills. But Zhang Yimou is such a craftsman, that he doesn't need much to make a great movie. The story is set during the cultural revolution, a period of ruthless oppression by the communist regime. The young girl Jing is being watched by the authorities because her father was a 'reactionary' and she risks losing her job as a teacher. During a trip to the countryside she falls in love with Sun. Her mother is afraid the affair will harm Jing's future career, and she forbids the two lovers to see each other. Zhang Yimou tells the story in a simple way, focusing on the two lovers. He uses title cards to make the story go forward, a smart move because it prevents the script from having to explain too much. In this way, Zhang concentrates on the story of Jing and her lover Sun, and nothing else. China in the seventies was a country where people led simple lives. Zhang emphasizes this by using simple props, like a goldfish key-chain made of yarn and beads, or a metal bowl with a special decoration. The hawthorn tree from the title also has a symbolic meaning, and in the very last image of the movie, when we see the tree blossoming, Zhang has an unexpected surprise that will make you smile. The acting is wonderful. The two leads tell just as much with their eyes, their laughs and their expressions as with their words. Take for example the scene where Jing gives her goldfish to Sun, and the camera lingers on their faces to show us how they feel. Wonderful film making. With this film, Zhang Yimou returns to his earlier style of film making, telling stories about the daily life in China. Under the Hawthorn Tree has more in common with his lesser-known films like Not One Less or The Road Home, than with his visually more spectacular films like The House of Flying Daggers, or even Raise The Red Lantern. Some people may be disappointed by the slow story, in which nothing spectacular happens. But some of history's greatest film classics are slow and subtle. In a way, Under the Hawthorn Tree made me think of David Lean's classic Brief Encounter, another story about a forbidden love, that stands out because of the impeccable directing and acting.

Jenny Sutton

The harsh realities of the 1970's cultural revolution in China are moved into soft focus by awesome cinematography, slow moving scenes and superb acting.The story is beautifully told, and although the ending is hinted at from an early point in the movie, it is nevertheless sad and moving.The grey and monotone scenery is punctuated with the bright colors of the volleyball uniforms, the red jacket, and of course the hawthorn berries which are all symbols of the couples' evolving romance.The proximity of the town to the village to the hospital, and the ferry versus the bus was a bit hard to understand. And how Sun managed to spend some much time in the Jing's town.

Harry T. Yung

To many who have been director Zhang Yimou's loyal followers for decades, this film must feel like home coming. While I enjoyed and appreciated his earlier films from Red Sorghum (1987) on, I am no loyal follower, and therefore said "to hell with him" when he degenerated to making trash after trash, culminating in "The curse of the golden flower" (2006) in his vain and naïve hope for Oscar fame. On the other hand, I do welcome the return of Zhang in "Under the hawthorn tree", to pre-5th-generation directors' simplicity and honesty.While adapted from a true story, what this movie shows us is certainly not something unique. More likely, there would have been countless such stories (consider the population of China) in the post-Cultural-Revolution era of the 70s, albeit perhaps with variations in details. Billed as "the cleanest romance in history", "Hawthorn" depicts how two "zhiqings" (young city-born "intellectuals") meet in a customary "sent down" (temporary deployment by school and government to the village to learn from peasants). The romance that budded in the idyllic setting continues back in the city. One obstacle is the girl's "rightist" background which means that she must be particularly careful to avoid being expelled from school (and subsequent teaching career) on any smallest excuse. With this the young lovers can cope, as they can afford to wait. But then, not unlike in some of the contrived and formulaic Korean romances in the 80s, terminal illness sets in. This is basically the simply plot.This movie stands out in its refreshingly simple narration, with sequences preceded by quotations from the original book in a fashion similar to the silent movies. The quotations however give you the sense of actually reading the book. It is moving in the most natural way, without any of the sappy tear-jerking devises that swarm the Korean romances. Cinematography is almost mesmerising. Zhou Dongyu, the 17-year old girl who won the part over thousands of contestants, is without question absolutely deserving – fresh, intelligent and innocent both, and unspoilt by professional training. Shawn Dou is also good, but his character is less developed – pure perfection to the extent of being almost angelic.