grayson-135-156418

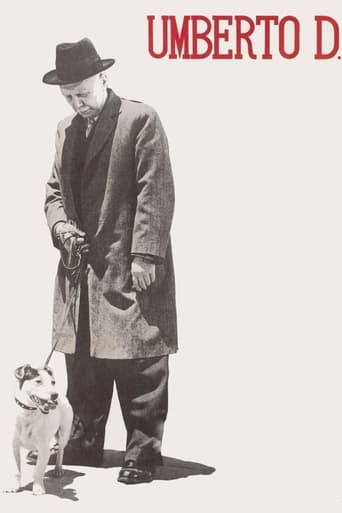

Labeled by some as the "epitome of world cinema", Neorealism is perhaps tautologically represented by its appeal to genuineness - a call to realism, a display of actual life. Italian Neorealist films like De Sica's Umberto D. embody this overarching value, made apparent by many deliberate choices in production. Top-billed actors in this film are truly not actors at all, but brought to the screen on appearance alone. They live out their own stories, as true to the self as they possibly can be, realizing this powerful authenticity. Antagonists, interestingly, are professional actors cast opposite their usual roles, allowing a small inconsistency with this effort that, to a knowledgeable audience, would provide a short, yet sharp, dose of excitement.

The most notable Neorealist pillar shown in Umberto D., however (aside from its setting at the Pantheon, of course), is its use of plot that is not exactly extravagant. The film is about a government retiree, and his loyal, canine companion, who struggle to make ends meet on his pension. A brief side plot exists as he interacts with his building's maid, and these are, more or less, the only large-scale stories told. To borrow from the television series Seinfeld, it's a film "about nothing" - but by telling this seemingly commonplace tale, De Sica opens this life and setting up to something beautiful. The simple story is mirrored by simple shots that other films, including those that came after this movement, would not dare. In one scene, the maid grinds coffee grounds - a task that would, in other films, take seconds - but in Umberto D., it is drawn out to its appropriate, real-life length. Seemingly banal details, like the building's ants, are shown with great intricacy. By placing emphasis on the minutia of day-to-day life, De Sica embodies us in the story, and it overflows with authenticity, making it seem as though the audience could jump through the screen and truly live these moments with the characters.

classicsoncall

Just recently I posted a couple of critical reviews here on IMDb about films that primarily deal with teenagers and young adults, stating how their appeal seemed to be somewhat limited to a target audience and not particularly popular for folks like me, a seasoned citizen already retired. So now as I contemplate on what I've just watched in "Umberto D.", I realize the shoe is on the other foot. Here's a film I can relate to from having lived a productive life, with an understanding of what the title character is going through in a desperate attempt to keep his apartment and ownership of his pet dog intact. Someone much younger will see the film as slow moving and boring and have an inability to relate. With that little preface out of the way, I'll get to the picture itself.A handful of reviewers describe the picture as neo-realist without explaining what that is. Very simply, director Vittorio De Sica uses real people, not actors, to tell his story, and uses real locations instead of filming on a set. It's a style that's been very successful for him, as anyone who's seen this picture or "Bicycle Thieves" will attest. The two movies are quite similar, as they both deal with impoverished citizens trying to make ends meet, living their daily lives in quiet desperation and not knowing what their situations will lead to. De Sica effectively balances this desperation with moments of subtle humor that diffuses some of the bleakness of the story being told. In this one, Umberto's pet dog Flike provides some of those moments, a memorable one was when Umberto had him panhandle with his hat because he couldn't force himself to do it on his own. There comes a point in the story when Umberto becomes particularly despondent, and he's asked by maid servant Maria (Maria Pia Casilio) at his boarding house what's bothering him. By this time he's been told he will be evicted, he's had a momentary respite at a hospital type clinic for an illness, and his dog was picked up by the city pound while he was absent from home. He's even unsuccessfully attempted to get acquaintances to lend him some money. For Umberto, the frustrations amount to "... a little bit of everything", as he even contemplates suicide as a final answer, though he has neither the will or the stomach for it. The story comes to a close on an ambiguously positive note, since we know as the viewers that Umberto's situation will not change as he playfully skips out of the picture with Flike at his heels. It's the type of ending that requires some contemplation, even though like Umberto, there's nothing we can do to help his circumstance, so all we can do is commiserate and feel compassion for the lonely old gent. Defining what will happen to Umberto rests with the imagination of the viewer.

George Wright

This movie from director Vittoria de Sica is a heartbreaking story of a destitute pensioner named Umberto Ferrari and his pet dog. The pensioner cannot bring himself to tell anyone of his difficult existence or to ask for help. Set in post-war Italy of the 1940's and 50's, the neo-realist movies of this period with their on-location shooting show the grinding poverty of many people at the time. With this vivid background, we see some very tender moments in the story that illustrate the bond between the man and his dog. We also get a sense of the mood in Rome at the start as police break up a protest by pensioners fighting for a decent income. Other scenes take the viewer into a hospital where patients recite the Rosary from their beds, have lunch at a pasta diner and go home to a walk-up apartment. With Umberto pitted against his cold-hearted landlady, we see how his life is made almost unbearable. In fact, the movie is very sensitive in its depiction of this man, one of many elderly people who were by themselves with little money. In this case, the elderly man, played by Carlo Battista, has a reason for living because of his canine companion. De Sica used amateur actors and Battista was a university professor in Florence who has captured the essence of his character. De Sica made his mark as the foremost director of the neo-realist school of cinema and as an accomplished character actor in his own right. I noticed the dedication to Umberto DeSica, who was apparently his father. In this film, DeSica has certainly produced an outstanding work of art about the plight of one aged citizen in a particular time and place. Thanks to TCM for its recent showing this neo-realist classic.

tieman64

"It (my film) is the tragedy of those who find themselves cut off from a world they helped to build, a tragedy hidden by resignation and silence, but one that occasionally explodes into loud demonstrations or is pushed into appalling suicides. A young man's decision to kill himself is taken seriously, but what does one say of the suicide of an old man already close to death? It's terrible. A society that allows such things is a lost society." - Vittorio De Sica Vittorio De Sica's "Umberto D" opens on a group of street demonstrators. They're an orderly mass of retirees, all demanding a pension rise. De Sica then focuses on one particular protester: Umberto Domenico Ferrari, a retired civil servant. He shares the name of De Sica's own father, a retried bank clerk, to whom the film is dedicated. Of all his works, De Sica would regard "Umberto D" as his personal favourite. In the West, it is regarded as one of cinema's seminal neorealist works. Upon release (and still in many places today) the film was harshly criticised for its saccharine and sentimental qualities. In truth, the whole neorealist movement tends toward contrived manipulation and sentimentality, often romanticising suffering and sanctifying the impoverished. De Sica would be ignored when he "left" the neorealist movement (in the mid 50s), but some of his best films were made in the 1960s and 70s.After hitting us with a flurry of billboards and angry chants, De Sica has the police arrive and the protests quickly squelched. White handkerchiefs wipe sweaty brows, subtle hints at white-flag surrenders. Men, organisers and union heads then squabble. We learn that the protesters were denied demonstration permits, the state planning in advance its motive for disbanding the crowds. The point is clear: in post-fascist Italy, fascism is far subtler. Cunning and manipulative, the authorities "contain protesters" under the guise of "restoring order" for the majority of the citizenry. What's staggering is the ordered, well behaved methods of both the protesters, the public and the police force. De Sica stresses obedience, professionalism, calm. Throughout the ordeal, traffic flows incessantly, the pensioner's cause invisible.The film then nosedives into its central plot, De Sica watching as Ferrari - who we learn has little money and was depending upon a pension rise - struggles to survive from one day to the next. And so we watch as friends and officials feign deafness when Ferrari asks for help, as landlords turn blind eyes to his plights, and as he pretends to have an illness so as to get admitted into a hospital which offers better accommodation than the outside world.Several scenes follow which resemble De Sica's earlier "Bicycle Thieves", Ferrari selling watches and items in an attempt to generate cash. Much of the film then revolves around Ferrari's attempts to locate his pet dog, which is lost on the streets and being hunted by a municipal pound responsible for capturing and exterminating stray animals. The dog's plight, of course, echoes Ferrari's. Neither seems to have a right to live, both are overlooked, both seem unworthy of care, and both are categorised by a bureaucratic state as being part of a social strata which it deems "necessary", "logical" even, to allow to wither and pass away. All Ferrari's struggles thus have a larger weight behind them, the audience always aware of the political forces obstructing the remedies to the problems encounters. The film then enters Visconti territory, in the way it shows various generations subtly pitted against one another. The postwar economic recovery benefits some, but others have been left behind as the nation moves forward. To the new, remobilized Italy, they are not essential. Ferrari thus exists in a kind of stasis, consigned to anonymity. People see him, but he is too distasteful a reminder, a totem of political memories which post-war Italy seeks to discard. The film ends with hints of suicide and shots of the old, feeble Ferrari inter-cut with happy, playing children; Italy's past and future, old and young. The film as a whole, and its climax, strongly resembles Kurosawa's "Ikiru", released the very same year as "Umberto D".The film boasts clear, crisp black and white cinematography by Aldo Graziati and continues De Sica's use of nonprofessional actors. Ferrari is himself played by Carlo Battisti, a former university professor. Ironcally, De Sica's film found itself, like Ferrari, battered upon release, the state and various film boards ashamed of both its subject matter and style. Indeed, the whole neorealist movement, with its socially investigative qualities, progressive voice and often Marxist overtones, proved worrisome for the Catholic Church and various Italian arms of power. There are even documented cases of Hollywood producers, distributors, studios and financiers pushing for the movement to be squelched (after the US conquered Italy, it extorted many favours from the new governments), as it was cutting into Western profits.Modern viewers unimpressed with "Umberto D" (it's a bit schmaltzy), may want to check out two excellent, similar recent films: "Wendy and Lucy" by Kelly Reichardt (obvious De Sica influences) and "Land of Plenty" by Wim Wenders. De Sica's last masterpiece was the overlooked "Garden of the Finzi Continis".8/10 - Worth one viewing.