WILLIAM FLANIGAN

Viewed on DVD. Restoration = ten (10) stars. Unlike most films from Yasujiro Ozu, here is a movie you have NOT mostly seen before you actually see it! This is mainly due to a plot that is uniquely divergent for this director (who is also a co-author of the script). It is a refreshing relief from the usual over-the-top depiction of tragedy in many/most dramatic films of the era. No over-blown emoting (except for the youngest lead actress), extensive distraught hand wringing or scenery eating. On the other hand, the serene depiction of an extended family confronting life-changing misfortunes is unrealistically presented as essentially a "business- as-usual," every-day occurrence. The lectern is disguised, but the viewer can not escape the nuanced feeling of being lectured by the Director on how financially well-off, contemporary Japanese families are supposed to confront and react to tragic events. This is a movie that projects the director's opinion of how Japanese society should be, not how Japanese society necessarily was in the mid 1950's. There is not much in the film that is new at the execution level. As usual, there are no surprises, since the script telegraphs all forthcoming events. Most of the director's filming techniques, trade-mark shots, and artifacts are the same as used ad nausea in other films (except for the absence of clothes lines and the frequent substitution of "side acting" for "back acting" this time). As usual, the film is much too long and dragged out. Pretty much the same (outstanding) leading actors/actresses are in residence. Studio sets have been recycled as usual: this family seems to live in the same house as all the other families seen in all the director's other films (complete with bell-ringing outside sliding doors). All establishing shots are at worm's eye level which usually cuts the actors off at mid torso. The schizophrenic film score is badly in need of a music editor to match music and themes with actors and scenes. Music ranges from rip-offs of contemporary Italian movies (especially during the opening credits) to very light-weight Wagner. To add to this sorry state, happy music often accomplices the depiction of somber screen moments. Cinematography (black and white) consists of static shots using graying filters for real exteriors and an antique, narrow-screen format. Subtitles are just right: they neither lag nor lead the clearly enunciated dialog delivery. So in the final analysis what do we have? A photo play that is definitely worth watching and watching in its entirety, although surviving repeat viewings may prove beyond challenging. WILLIAM FLANIGAN, PhD.

Andres Salama

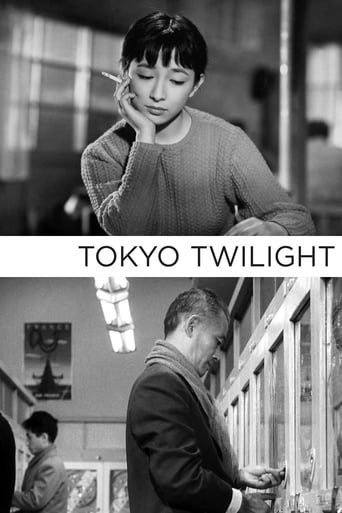

Tokyo in the mid 1950s. In this stereotypical women's picture, a single, middle aged man (Chishu Ryu, an Ozu regular), tries against all odds to raise his two grown troubled daughters. One (the great Setsuko Hara, another Ozu regular) is a single mother who has left her husband and return to his father's home. The younger daughter is even more troubled, is surrounded by bad companies, and has become pregnant by her no good boyfriend. Soon, the two sisters find in a mahjong joint their long lost mother, who seems curiously unmoved at learning that her son has died years ago in a climbing accident. The sloppy plot hurts the movie a lot (only in bad melodramas, one of the characters commits suicide by throwing herself under a train, but doesn't die until she tells her story). To its credit, though, this film tackles the issue of abortion decades before western films did, but this is still minor Ozu, somewhat moving, but done in by its unnecessary melodrama and its barely believable plot points. There are many movies Ozu made during this era - from Tokyo Story, Floating Weeds, Early Summer, Late Spring, Good Morning, End of Summer, etc., that are better than this. Still, worth seeing if you are not expecting a masterpiece.

rschmeec

This is a relatively "dark" film, symbolized by the cold weather outside throughout the film, and the various ways (wearing masks, sitting close to the fire, snuggling up) in which the characters cope with the cold.I cannot agree with the previous review's strictures about the leading male character, that he is paternalistic, passive, and judgmental. What came across to me was that he cared deeply for his children and accepted his responsibility as a parent to address their problems. He has been abandoned by his wife and the mother of his children, he says he has done the best he could to raise them, at the same time acknowledging the need for children to have two parents. The theme of parental responsibility seems a common element in this with the last Ozu film I saw: THERE WAS A FATHER.Although this is a rather "dark" film, the ending, like that of many of Shakespeare's plays, ends in some form of reconciliation: the one daughter wanting to start a new life, the other deciding to return, with her child, to her husband, from whom she has been separated.

alsolikelife

A deeply, uncharacteristically dark film, even among other "dark" Ozu films (i.e. A HEN IN THE WIND, EARLY SPRING) that may require a theatrical setting for the viewer to be fully absorbed in the strange, dark textures of the world Ozu presents. I myself was pretty alienated for the first 1/2 hour or so until the wintry chill of the mise-en-scene (brilliantly suggested in the slightly hunched-over postures of the characters) found its way into me instead of keeping me at arm's length. And from there this story builds in unwavering intensity as it follows a family on a slow slide into dissolution: a passive, judgmental patriarch (played by Chisyu Ryu, subverting his gently accepting persona in a way that is shocking), his elder daughter, a divorcee with a single child (Setsuko Hara, playing brilliantly against type -- who'd have thought the sweetest lady in '50s Japan had such an evil scowl?), and his younger daughter (Ineko Arima, a revelation), secretly pregnant and searching for her boyfriend, get a major shakeup when their absent mother, who the father had told them was long dead, re-enters their lives. Ozu's vision of post-war Japan and how the sins of one generation get passed on to the next, illustrated brilliantly by a series of parallels drawn sensitively between characters, manages to be both compassionate and scathing -- even a seemingly cop-out happy denouement is embedded with a poison pill. A masterpiece, without question, one that throws all of Ozu's depictions of modern society in a beautifully devastating new light.