jacobs-greenwood

Its most basic flaws are its awkward, clumsy attempts to make a social statements - about race and humanity - which are unearned by the depth of its exploration. However, given the fact that the movie was released years before the Civil Rights Act was signed by President Johnson in 1964, we should probably cut the film-makers some slack for their early effort. It is a shame though that such a tantalizing subject - being the last person(s) on the planet, and the root causes of such a predicament - is so muddled.Though it was clearly intended, the story doesn't quite succeed in communicating its forewarning message(s) to/about mankind because it's too narrowly and inadequately (per the censors and/or fears of audience reaction?) focused on racism.The film's strengths are its depictions of a post apocalyptic world and some of its character's actions that follow, but the producers' (Harry Belafonte among them) tunnel vision caused them to give short shrift to the other 'big picture' issues.This movie has to have been one of the first 'last man on earth' sci-fi dramas. It precedes the three movies based on Richard Matheson's novel I Am Legend, and was obviously a model for them since many of the scenes and props are so similar. Mannequins as companions and the use of a short wave radio to contact other survivors are among the staples not previously listed.After being trapped underground for nearly a week, a miner (Belafonte) emerges to find that he's seemingly the only person left alive on the planet. From Pennsylvania, he makes his way to Manhattan where he finds deserted streets, except for the exit routes - which are clogged with empty automobiles - on the edges of the city. No bodies are to be found anywhere. He enters a radio station which is still running on backup power and learns about the fate of civilization via an audiotape recording: nuclear isotopes were released in the atmosphere, the resulting clouds circled the globe killing everyone within five days but then disappeared without leaving any residual radioactive danger. After expressing some grief and anger, this 'last man' busies himself by outfitting a penthouse apartment with various amenities including generator electricity while he rescues various cultural valuables from deteriorating libraries and museums.Enter a woman (Inger Stevens). She has been watching him without revealing herself until he, frustrated by his loneliness, throws an ever smiling mannequin out of his apartment's window and she screams, assuming that he's just committed suicide. Hearing her shriek, he rushes to meet her and they have a rather unbelievable conversation. Initially, she is credibly frightened of him, but then both are rather standoffish given their situation. Over the passage of some time during which he provides her apartment with electricity and installs a telephone between them, they become platonic friends.Then it is her - not him - that mentions the possibility of a closer (e.g. sexual) relationship, but it's him - not her - that declines, citing their differences in race. In a role similar to those that were or would be played by Sidney Poitier, Belafonte plays the noble chaste black man; it is he that enforces the separation between himself and the white woman. This conflict causes their separation. Weeks pass until their reconciliation - a birthday celebration for her - but it's filled with contradictions: he gives her a gigantic diamond, creates a romantic candle-lit dinner environment complete with a custom record he'd made that includes his singing a love song but then, despite her invitation, he refuses to join her and instead insists on assuming a stereotypical waiter role.The third act in the drama involves the discovery of another male survivor (Mel Ferrer), who'd been boating for six months presumably in search of others; it's never explained how he managed to survive the holocaust. The boatman collapses from exhaustion, so Ralph (Belafonte) and Sarah (Stevens) work together to nurse him back to health.Once on his feet, Ben (Ferrer) is direct and unapologetic about his sexual desire for Sarah; he also senses her love for Ralph. But even though Ralph intentionally stays out of the way, doing his best to facilitate the other two's relationship, Ben comes to view the presence of the all too perfect handyman as a threat.Viewing Ralph as an 'opponent' that needs to go away, Ben tries to force a showdown. From here, the drama gets even sillier: a chase that beckons The Most Dangerous Game (1932) etc. is on - with Ben claiming the high ground, shooting his rifle from atop the skyscrapers, while a reluctant (though now armed) Ralph runs below among the streets. An aimless Ralph comes to the United Nations where he reads this inscribed passage:THEY SHALL BEAT THEIR SWORDS INTO PLOWSHARES. AND THEIR SPEARS INTO PRUNING HOOKS, NATION SHALL NOT LIFT UP SWORD AGAINST NATION. NEITHER SHALL THEY LEARN WAR ANY MOREHe then throws down his weapon and confronts Ben, telling him to drop his weapon and saying that "it's all over". After a brief scuffle, Ben asks why Ralph won't fight and prepares to shoot him at point blank range but can't saying "if you were afraid, I could do it" before walking away. Seeing this, Sarah approaches Ralph and finally gets him to take her hand. She then calls to Ben "wait for us" and, after the camera angle changes to a birds-eye view, the (Miklos Rozsa) score's volume rises as the words THE BEGINNING appear on screen.

A.N.

This is not a dull movie but when you really examine the plot it makes little sense.What happened to all the people killed by radiation? They wouldn't just vanish. Evacuating everyone from a huge city like New York seems impractical. Where would they all travel to?Why would a guy who's got experience with mines and power supplies not even think to try the tap water in an apartment vs. lugging water upstairs? People would automatically at least turn a spigot once.Why are so many guns tossed away in temporary fits of disgust? In a future like that, people would horde guns for self defense against the dark forces. Or at least hunting, if any animals survived.Last but not least, why would that same (black) guy, in proximity to an extremely shapely white woman, make race such an issue with almost nobody else around to care? Good grief, man, just go for it!I found this film too tunnel-visioned to be realistic, given the circumstances of its setting. It forced a narrow, racial concern into a world where it no longer applied. But it's well made enough to be worth watching. The ambiguous ending is also interesting, though its practical implications are risqué.

Robert J. Maxwell

It resembles closely the pilot episode of "The Twilight Zone," called "Where Is Everybody?", only this time it's not a dream. Harry Belafonte is trapped in a caved-in mine and survives an attack of radioactive something or other, the kind that kills everybody without leaving any untidy corpses around.Belafonte digs his way out, discovers what happened, and makes his way to Manhattan, where he finds nothing but emptiness. He fixes up a block of New York with a generator and lights but is despondent and lonely -- until blond, sexy Inger Stevens shows up. They're both delighted. He fixes her a flat in the same building as his and they get to know one another, well enough so that Belfonte, a black man, confesses that he loves her but, what with his race, they live in two different worlds. She says nothing about love but, just as he's good with things, she's practical about relationships. "We're the only two people left alive." Not quite true. Mel Ferrer stumbles into their little nest. They nurse him back to health and it complicates the tentative arrangement. He's not a bad guy, but as Stevens describes it, Belafonte can't make up his mind about what he wants, while Ferrer knows exactly what he wants and will stop at almost nothing to get it.It's all believable enough. There are three people left alive on earth. The woman worries about which man she should marry, and the two men plan to murder each other.Belafonte, although confused and embittered, is clearly the more noble of the two. He puts an end to the shooting match by throwing away his rifle and announcing that he's leaving for parts unknown. Stevens talks him out of it and her pale white hand takes his strong dark hand. Then they hurry to catch up with Ferrer and he takes Stevens' other hand.What -- asks the discerning viewer -- is going to happen next? Don't ask. Why SHOULD you ask? The writers certainly didn't. Maybe polyandry.It's an interesting movie until the appearance of Mel Ferrer, who is a nuisance. Inger Stevens is visibly horny and at one point, when Ferrer forces her into a dark niche in the row of skyscrapers, she says, "Do you want to kiss me? Make love to me? Go ahead." Until then we've seen nothing but her growing affection for Belafonte.It must have been a shocker in 1959. The South still had "white" and "colored" drinking fountains and johns. If you wanted a hamburger you didn't sit at the counter; you waited at the take-out window. This was considered normal.There are some effective scenes, such as Belafonte first wandering the deserted streets of the city and shouting up at the stone cliffs that hover over him, the thousand windows like dead eyes, and Belafonte screaming, "I know you're there! I can feel you watching me!" And again, when Stevens gaily asks Belafonte to cut her wavy blond hair. He doesn't look forward to the intimacy of the act and begins cutting carelessly, increasingly angry, blowing the fluffs of severed golden hair from the back of his hand. She finally tells him he's hurting her and he throws the scissors down and walks off.But the musical score is by Miklos Rozsa and practically duplicates all his other scores. His work was dramatic but dull. The performances are alright. Belafonte is handsome and convincing, and Ferrer is an effective catalyst. Inger Stevens does fine in the role of a woman whose part is full of blanks. It's the script that's the problem. I understood what Belafonte was about, and I had a general idea of what Ferrer was up to, but Stevens was impossible to figure out, aside from her terrifying thought that she might never be married. (Is that from the 1950s or what?) The climax is a cop out. Nothing is resolved. All such endings -- in which the writers have entirely run out of ideas except "let's not offend anyone who might buy a ticket to the movie" -- should be abjured, banished from the screen, sent to the lesser moons of Jupiter.

peterpants66

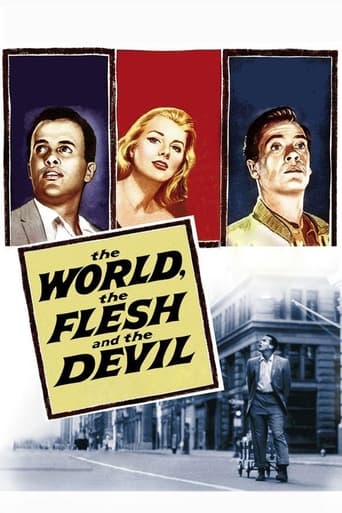

Don't judge a book by it's cover, right? Wrong, at least in this case. I picked it up recently with no cover, just a homemade sticker with this weird title, probably one of the best titles ever. I had no idea what this movie was about, the guy at the checkout looked at the title and then me with some disdain. I thought it was going to be a movie about religion, which in some ways i guess it was. The movie concerns the interaction between three people who survive a nuke-attack and end up in NY of all places. So it was kind of a nice surprise, and a premise that doesn't get looked at very much. Sure people and zombies can survive a nuke, but this movie is just THREE people, one of them being Harry Belafonte. This is an old flick, a bit talky, the title might be the only memorable thing about it. Blargen.