maurice yacowar

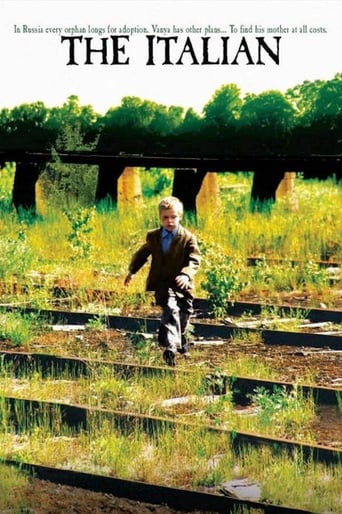

Andrey Kravchuk uses a six-year-old orphan's quest to find his mother to project a corrupted, predatory and deracinated Russia. Little Vanya resists adoption by an Italian couple because he wants his mother to be able to find him. Against all odds he finds her. In an improbable happy ending, she takes him in and his friend Anton from the orphanage is sent to the Italian couple in his stead. Unlike his other friend's desperate prostitute mother, who ends up a drunken suicide, Vanya's mother has a home and a job as nurse, so she can now take care of him.The film's key theme is the predatory nature of everyone around Vanya. As an orphanage staff member reads from Kipling's Jungle Book, Vanya is the Mowgli figure raised amid wolves with an occasional kindness to remind him of what humanity should be.In the orphanage the older boys have institutionalized their predation, with vicious beatings and the exploitation of the vulnerable. The girls are sent out as prostitutes and the young boys have to turn in their meagre carwash earnings. It's a parody of the socialist community, as the girl who helps Vanya escape says the pooled money belongs to all of them so she could take it. It's the empty form of socialism without the generous spirit. Though she virtuously teaches Vanya to read and tries to rescue him, her instincts are also predatory as she seeks to exploit anyone else she can.The toughs who rob and beat Vanya at the train tracks are an outlaw version of the orphanage's young exploiters. They won't give him any break but in the bones. The teenage gang that saves Vanya from the orphanage's manager are a third group of semi- organized violence, hanging out bored, eager for a fight. The three groups of young people form an aimless, spiritless and needy generation with no values or purpose. They provide a bleak vision of Russia's future. The orphanage administration comprises three adults. Madam is a corrupt capitalist, obsessed with profiteering from the adoptions, happy to spread bribe money around to get her way. One colleague is a beaten man, rueful of his failed chance to have been a pilot. The other is a more aggressive brute, with a sexual interest in Madam, but Vanya wins him over by slashing open his own arm in desperation. His beating by the gang may have eased his brutality towards Vanya. The title — Vanya's new nickname at the orphanage — is ironic because the boy doesn't want to leave cold wet Russia for the warmth of Italy. He wants his mother, who ultimately provides a warmth deeper than the climate.The closing closeup on Vanya evokes the famous last shot in Truffaut's The 400 Blows. Where Jean Pierre Leaud stares out on an empty sea, uncertain, here Vanya beams at his beautiful blonde mother and spells out the happy ending in a voice-over letter to friend Anton. Against the bleak social landscape the film finds a surprising hope in the young star's performance. His face and body provide emotional animation and he proves of increasing resourcefulness in making his way back through enemies and abusers to his maternal roots. In finding his mother he finds the old Mother Russia, an ideal lost amid the current corruption.

manjits

"The Italian", a debut film by Andrei Kravchuk, is an outstanding film by any standard; and yet the film failed to win any major awards – not even the consolation of a Best Foreign Film Oscar. It won the minor category of Children's film award created for the purpose at Venice, but nowhere else, as if a film about children automatically becomes a children's film.Three reasons spring to mind; it was a commercial dud possibly due to lack of commercial skills of the makers; contrary to public perception, shock value and financial success rules the fate of a movie even at the top festivals where the judges are mostly the mega-stars from Hollywood and around the world; and the debut production of a young person from a poor country still on the other side of the divide stood as little chance of an award as of Castro winning a Nobel Peace Prize.So what did I find exceptional in the movie? To start with the least important, the cinematography was par excellence. The depiction of desolate, gloomy environment of Russian winter, with telephoto shots of barbed wires quivering as if in the cold air; the claustrophobic shots of vast landscape (even if done through back projection) from the inside of cars and train were awesome.The second most outstanding quality of the film was the acting, particularly by all the child actors. It wasn't just great; it was breathtaking in its realism, as if the kids were chosen from an actual asylum which they weren't. The adults had no chance to compete against such talent, but managed to perform professionally.The most outstanding characteristic of the film got to be the director, whose command in every field – music; editing; locations; camera angles; choice of lenses and suppression of any tinge of sentimentality – was evident.I don't accept it's a rehash of Dickens's Oliver Twist suggested by some commentators. The harsh brutality of criminal gangs of 18th century Britain in Oliver Twist has nothing in common with the sad declension of Russian society and morale since the glasnost. If anything, the story has more in common with the magical realism of Garcia Marquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude.That's why the unsentimental ending gels with the mood of the movie.

sergepesic

One of the reviewers was trying to convince us that this movie is nationalist, because it portrays orphanages and their staff in negative light. I have to strongly disagree. The bleakness of day to day life in Russia in transition, that this film vividly brings to life, can hardly be a fodder for any nationalist propaganda. Most of Hollywood movies are way more nationalist and self-deluding than anything we saw in this powerful little movie. Director Andrei Kravchuk tells this tragic, but ultimately uplifting story with just the right amount of sentiment.It ends with a slight touch of fairytale. After all, most of the time, life is a mix of tragedy and endless hope.

Chris Knipp

The Italian/Italianetz is a good use of neorealistic effects almost worthy of Zavattini and De Sica to tell the story of a Russian orphan at the present time, a boy of six who's set up for adoption by an Italian couple and then determines to sneak off and see if he can find his own mother instead. Arranging adoptions on a freelance basis, apparently, outside the chaotic social system of present-day Russia, is a lady they call Madam (Mariya Koznetsova), plump, bossy, slick, followed around by a glum factotum, Grisha (Nikolai Reutov), who's her chauffeur, toady, and sometime lover. She makes a bundle out of each successful adoption by foreigners and makes free with bribes and threats to be sure her deals go through. A product of modern Russian capitalism, the money-mad Madam is more villain than fairy godmother.Using a photo followed up by an on-site interview at the detsky dom (children's home), Madam has arranged with an Italian couple, Roberto and Claudia, to adopt young Vanya Sonetsiv (Kolya Spridonov). But then when Vanya meets up with a remorseful drunken mom who apparently commits suicide after learning her child has been adopted and taken to Ialy, he gets the urge to investigate his own record. Everybody acts like he's such a lucky guy. But supposing he goes off with Roberto and Claudia? Mightn't he miss out on a chance to be reunited with his own mother, should she have a change of heart and want him back? Is there such a chance, though? And where is his mother? To find out, first Vanya has to learn to read – a detail the orphanage has neglected – and find a way to get a look at his file.The detsky dom's administration is not exactly on the up-and-up. The wild looking director (Yuri Itskov) is drinking up all the funds, and to fill in the vacuum this leaves a small clique of older boys to pretty much run the place and its finances, like a rawly capitalistic petty mafia, sporting scars, tattoos and muscles and throwing around words like "cosa nostra." Led by a boy named Kolyan (Denis Moiseenko), they have their own little systems of businesses and payoffs. And this shadow regime, up to a point anyway, really seems to work. The kids' beds are clean, and the girls mend their clothes and read them fairy tales at bedtime. But it's clear there's no pathway to a better future in the life here. Vanya, whom everybody now calls "the Italian" because of the good fortune they feel he's destined for when the papers go through in a month or so, now wangles his way in with the older boys, and they help him out. Among these undergrown mafiosi is a girl named Irka (Olga Shuvalova) who they pimp out to truck drivers. It's she who teaches Vanya to read. The big boys help Vanya break into the room where the records are kept and he gets the address of the maternal home where he came from, and Irka takes Vanya to the railway station, having robbed the boys' current till and intending to run off with him. Madam immediately finds out that Vanya has disappeared and, standing to lose her payoff if she can't deliver him to the Italian couple, she sets off in hot pursuit with Grisha.What follows is a wild chase in which Vanya shows what he's made of. Nothing, and that includes some pretty rough scrapes, can stop him from his relentless flight and quest. The Italian never loses its authentic flavor either as it moves toward an emotionally satisfying if somewhat hasty finish Still, it's obviously in the first half of the film that we get our best look at this world and its people and the Russian orphan problem. It might even have been a better treatment of that issue if some of the earlier scenes had been allowed to play out a bit longer.The San Francisco Chronicle's venerable Ruthe Stein called this the best "naturalistic performance by a Russian child actor since Kolya a decade ago." Spiridonov is very effective and appealing in his role, and perhaps The Italian has some links with that somewhat saccharine earlier film. But The Italian is more chastening than Kolya. A more appropriate recent comparison (and another great youth performance in Russian) is the picaresque, unpredictable Schizo (2004), directed by Guldchat Omarova with the 15-year-old Oldzhas Nusupbayev. The Italian isn't saccharine, but it's also not as grim a view of the plight of lost Russian children as Lukas Moodysson's deeply depressing 2002 film Lilja 4-Ever. See all four and decide for yourself which feels like the most convincing and cinematic story of Russian childhood. You'll have to consider whether Kravchuk undercuts or strengthens his material by turning it into a fairy tale. It was the urge to depict a growing social problem and at the same time tell an engaging story that must have drown a documentarian like Kravchuk to this subject. He has worked well with his non-actors and his writer Andrei Romanov, and Aleksandr Burov has provided a misty, subtly colored cinematography.