WILLIAM FLANIGAN

Viewed on DVD and Streaming. Restoration = ten (10) stars; cinematography = nine (9) stars; score = eight (8) stars. Director Masaki Kobayashi's two-part(complete with scored intermission), moderately-sized, propaganda epoch using coal mining in China as a backdrop. Scenes of high drama are often book ended by heavy-handed scenes that stretch credulity to the point of unintentional humor and self caricature. Four prime flavors of protagonists bounce off one another in the Director's tale: a newly-hired, mine management-team member who is a compassionate liberal; conservative mine managers/labor-enforcers; military mine guards/minders; and ethnic/semi-ethnic "Chinese." Kobayashi seems to be struggling to maximize the inclusion of events depicted in the original source material (a super-sized contemporary novel) that results in loss of dynamics and consistency especially in the second half of the movie (the latter is also too long). The Director provides a number of truly startling and indelible scenes including: half-dead/dead Chinese slave labors being disgorged/pulled from sardine-can military box cars; and the execution (by samurai-style beheading) of slaves who may (or may not) have tried to escape. Exterior scenes shot at an immense open-pit coal mine in China are spectacular (the coal mine is the real star of this film!). Kobayashi also displays many hard-to-swallow oddities starting with his film's central plot point: a conservative mining company hires a left-wing, college student (who thereby avoids military call up) to booster the management team of a brutal and labor-intensive mining operation in far off China. There are many more. Among my favorites: the absence of any freshly mined coal (just pieces of jagged light-colored "ore"); a 3,300-volt electrical fence (to prevent Chinese slaves from escaping) complete with an impressive high-power infrastructure, but no visible means to power it all; labored Chinese dialog phonetically delivered by Japanese actors (ethnic Chinese physical and voice actors seem to be among the missing); and Chinese "comfort women" depicted as seasoned pros who clearly seem to enjoy practicing their profession ("happy hookers") and are never fully booked (about 50 sex workers are supposed to be servicing 10,000 non-slave and 500 slave labors!). Acting is OK but trends toward the histrionic and hammy in the second half of the film. Cinematography (wide screen, black and white) and scene lighting are excellent. Score is very good, but tends to have too many redundant phrases in its orchestration. Subtitles can be a bit long given their rapid flash-by rates. Most signs, armband, etc. are translated. Audio distortion mars the orchestral recording for the opening credits. Restoration is as good as it gets--the film looks like it was just released! Just go with the flow in this partial rewrite of history. WILLIAM FLANIGAN, PhD.

OttoVonB

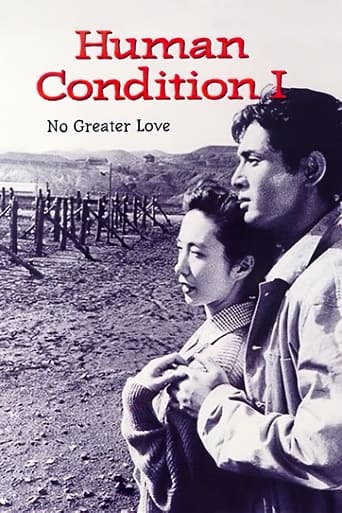

Masaki Kobayashi's reflection on the Japanese experience in occupying Manchuria, fighting World War II, and dealing with defeat is a staggering piece of cinema. Clocking in at just under 10 hours, "The Human Condition" – what a title! – takes us on a journey with Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai) through a POW film, a war film and a survival film, tied together by a loose love story, weaving all these strands together with great care over its epic but impeccably paced run-time.The first part sees Kaji, a young, well-to-do Japanese, begin work as labor supervisor in a POW camp in occupied Manchuria. What could have been an interesting honeymoon with new loving wife Michiko and the start to a promising career slowly devolves into a nightmare: Kaji tries to stay true to his human principles while getting increasingly tangled in a complex web that involves escaping prisoners, abusive guards, and a tyrannical, bullish army that is above the law.As an indictment of the Japanese Imperial Army, it is all the more haunting for coming from one who served under it. And to Kobayashi's credit, never does this come across as a crass moral lecture. It is a stunning, gripping study in mounting desperation, anchored by a powerful turn from the ever-dependable Nakadai.Japanese cinema of this period has its quirks, stylish acting and a tendency to melodrama that can bemuse Western viewers. While I find Kobayashi less impaired by these traits than many of his contemporaries – especially in the cold, restrained anger and sorrow of Harakiri, his masterpiece – he gets heroic support from his star of choice. Far from the histrionics and bravado of a Toshiro Mifune, Japan's other megastar of the 50s and early 60s, Tatsuya Nakadai's magnetic charisma is far more subdued and heartfelt. Though our hero is at times unbelievably decent, perhaps buoyed by his youthful optimism and love for his wife, Nakadai makes every situation and painful decision resonate.The technical credits are the usual for this under-appreciated director's work: arresting visuals, sweeping movement, carefully crafted sets. And the supporting players leave their mark, with a stand-out in each episode. In this instance, particularly Kaji's conflicted assistant, originally mistakable for a simple brute, finds very different ways of dealing with his own crisis of conscience.This is definitely a film you have to see. Just make sure you clear your schedule, as you don't want to spread the viewing chunks too thin if watching in fragments

MartinHafer

This is the first of three very long movies that are based on Jumpei Gomikawa's six-volume series. It is set during WWII and is about a Japanese man named Kaji. Kaji is a very liberal man for the times--something that COULD be very dangerous in the militaristic Japanese society. When he's called up to fight in the war, he's torn. He's basically a pacifist at heart and cannot see himself killing another. Luckily for him, his boss gives him a choice--report for military duty or go off to Japanese occupied territory to be the production head for a forced labor camp. Not surprisingly, he goes to work at the camp--and takes his new wife with him.When he sees the camp, Kaji is angered--the soldiers brutalize the workers and have absolutely no regard for them. The camp is also rife with corruption. He insists that the beatings MUST stop and he is opposed by the staff--but he's not willing to budge and he has the authority to make it stick. Fortunately, when the workers are better few and treated well, production increases dramatically. However, when there are prison escapes, the hardliners press for a return to brutality. After all, they feel, these aren't exactly humans--just Chinese and Korean conscripts and, worse, Japanese political prisoners. What is Kaji to do? As the film progresses, to save himself he may need to forget about his high ideals. But, can he live with himself? And what about his marriage? Because of the job, he's withdrawn and miserable--and a lousy husband. I'd say more, but this would ruin the film.Overall, an excellent film that is worth seeing. I am excited to see what happens in the second film, as at the end of the first there is a BIG twist and Kaji's world has been turned upside down in the process. My only question is could this film STILL be a bit sanitized? From what I've read about these camps, they were MUCH more brutal than even the film portrayed.

MisterWhiplash

Masaki Kobayashi's dream project was the Human Condition adaptation, and he pulled it off as a brilliantly told and filmed epic that tells of a man trying to cling to his humanity in inhuman circumstances. All three films have wonders in various supporting performances and set-pieces that astound with their moments of poetic realism, and the sum of it all makes Lord of the Rings look like kid's stuff. In the case of the first feature on the trilogy, No Greater Love, we're introduced to and see the young, idealistic and essentially good-hearted Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai) as he gets a job as a labor supervisor at a POW camp in Manchuria following an impressive paper presentation. He wants to do his best, but the 'powers-that-be', which include the stalwart boss and particularly the fascistic Kempeitai (army personnel on site), keep things always on edge with tension, and as new Chinese POW's roll in and he finds himself torn: how to keep production up of the ore while also not becoming a monster just like the other "Japanese devils" to the POW's.While the story has an immediate appeal (or rather connection-to) the Japanese public as a piece of modern history- the occupation/decimation of Manchuria and its people- none of its dramatic or emotional power is lost on me. Kobayashi is personally tied to the material very much (he himself fought in the war and immediately bought the rights to the 6-volume series when first released), but he doesn't ever get in the way of the story. Matter of fact, he's a truly amazing storyteller first and foremost; dazzlingly he interweaves the conflicts of the prisoners (i.e. Chen, the prostitutes, Kao) with Kaji's first big hurdle of conscience at the labor camp as he sees prisoners treated in horrible conditions, beaten, abused, and eventually brought to senseless deaths thanks to Furyua and his ilk, and finds himself brought to an ultimate question: can he be a human being, as opposed to another mindless monster? Kobayashi creates scenes and moments that are in the grand and epic tradition of movies, sometimes in beautiful effect and other times showing for the sake of the horrors of wartime (for example, there will never be as harrowing an exodus from a half-dozen cattle cars as seen when the Chinese POW's exit from there to the food sacks), and is able with his wonderful DP to make intimately acted scenes in the midst of wide scapes like the outside ore mines and the cramped living quarters or caves. And damn it all if we don't get one of the great scenes in the history of movies, which is when the six "escapees" are put to execution with the prisoners, and horrified Kaji, watching in stark, gruesome detail. Everything about that one scene is just about perfect.But as the anchor of the piece (and unlike the other two films, he's not even in every scene of this part), Tatsuya Nakadai delivers on his breakthrough performance. Kobayashi needed a bridge between pre and post-war Japan, and Nakadai is that kind of presence. But aside from being an appealing star- the kind you don't want to avert your eyes from- he's mind-blowingly talented be it in subtle bits of business or when he has to go to town in explosive emotional scenes (or, also, just a twitch under his eye in a super-tense exchange). This goes without saying other actors right alongside him- Aratama, Yamamura, Manbara- are perfectly cast as supervisor, prisoner, prostitute, wife alike to Kaji. And yet, for all the praise worth giving to the film, one that gets even better in its second half than its first, this is only the first part!