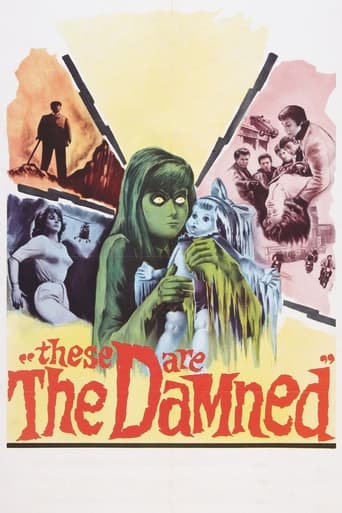

bkoganbing

You know the most frightening thing to me about These Are The Damned is had this film been done by some private mad scientist it might have qualified as one of those old PRC or Lippert films. But as the experiments were done apparently with the sanction of the British government and their best scientists you can gasp at the sheer inhumanity involved. MacDonald Carey is an American tourist who gets picked up by Shirley Anne Field, but she's a shill for her brother Oliver Reed's leather clad Teddy boy gang who mug Carey. But when her brother who shows the most obsessive incestuous interest since Paul Muni had for Karen Morley in Scarface she flees with Carey on his boat to a mysterious island which is in reality a government facility where Dr. Alexander Knox is conducting some frightening experiments with children. Children by the way who think they're on a spaceship. He's injecting them with radiation and looking for ways they can survive with radioactive bodies in a post atomic war world. Interesting also that only white kids are chosen. An interesting commentary in that while kids are experimented no one seems to care if other races survive.I agree with one other reviewer in that MacDonald Carey is too old for the part. Still he gives it his best shot as he and Field and Reed all trapped on the island.These Are The Damned is one far out, freaky, frightening film.

utgard14

Hammer sci-fi drama is something of a Village of the Damned knock-off that takes awhile to get going. First half is devoted to drama of American Macdonald Carey romancing British Shirley Anne Field, who is the sister of a biker gang leader (Oliver Reed). This is all fairly tedious with only a hint or two of the sci-fi elements coming later in the film. So make sure you sit with it through all this. Also be prepared for a very annoying song to get stuck in your head. "Black leather black leather smash smash smash" repeats over and over. Anyway, Carey and Field go to a clifftop house to get away from her psycho brother. But Reed and gang show up and chase them. The two eventually find themselves among a group of weird children who are part of some kind of government experiment. It's here where the movie gets interesting.Macdonald Carey always seemed like a weak leading man to me and I'm not surprised his movie career never took off. He would find his biggest success on TV soap opera Days of Our Lives for decades. Oliver Reed is fine, though his biker gang seems a somewhat laughable threat today. Shirley Anne Field is alright for a rather flimsy part. Veteran actor Alexander Knox brings some class to the film. Viveca Lindfors offers a strange performance where she seems oddly flirtatious with every male she shares a scene with, though nothing ever really comes of this. I don't even think it was part of the script. It just seemed to be something Lindfors threw in there. A decent drama with sci-fi themes and a powerful ending. Worth a look but requires effort.

Bribaba

The seaside resort of Weymouth is the unlikely setting for this 1963 Joseph Losey film. It also happens to be the home of a biker gang who act tough by strutting around town in black leather jackets and… whistling. The leader of the gang (Oliver Reed) is unhealthily protective of his sister's chastity (Shirley Anne Field), though he's not above using her to lure men into honey traps. She, in turn, gets involved with an American yachtsman (McDonald Carey), much to her brother's rage. Meanwhile, there's a parallel scenario involving an eccentric sculptress (Viveca Lindfors) and a mysterious military base on the cliffs where a group of children are held captive in a secret bunker, a lair not too dissimilar to the one Kubrick used in Dr Strangelove a year later. The two narratives merge when the quarrelling trio from the first scenario invade the base via a secret entrance and discover that the abducted kids harbour a terrible secret; one that involves a dead rabbit, the black death and their permanently freezing temperatures.Losey's direction gives the film a lot of credibility while Hammer regular DOP Arthur Grant makes everything look shadowy and sinister. The big let-down is the script, especially the embarrassing incidental dialogue. The 'dammed' of the title and the presence of the children suggest the work of John Wyndham, however, the story is based on the novel Children of the Light by H L Lawrence. Rumour has it that Losey completely rewrote the script (unaccredited) in his determination to make a 'moral' statement following his Hollywood blacklisting. This is very strange if true, for the core narrative is so entertainingly mad that it's hard to see where any such statement would make an impact. A moral maze this film isn't. The recent anamorphic transfer features the uncut version of the film, In the original print the US distributors snipped out some of the social comment, unwittingly providing an example of the prevailing paranoia of the period.

agreaves-8-151592

That the very mention of the word 'Hammer' brings to mind the Gothic settings, garish colours and tightly corseted maidens of British horror films of the 1950s and 1960s might explain why Joseph Losey's The Damned is something of an oddity. That Hammer is often seen as British cinema's only viable claim to an indigenous phenomenon gives a further indication, because The Damned is transnational; directed by an American filmmaker, with an American distributor (Columbia) and, it could be argued, rife with American themes - specifically the connection of rock n' roll culture to violence and the threat of atomic science on mankind. The setting here is not a fog filled stage set masquerading as period London or Eastern Europe but a post-war seaside town (Weymouth) terrorised by a gang of recalcitrant teddy- boys led by Oliver Reed's menacing hoodlum. The scientists are not camp, eccentric, wild- eyed mad men creating monsters and surrogate families in outrageous laboratories using vague and nonsensical science but are government men experimenting on children with atomic power. The solid and steady British directors employed by Hammer make way for an American 'auteur' who, stigmatised by the House Un-American Activities Committee, had been forced to move to Britain and adopt a pseudonym. Instead of Cushing and Lee doing battle as literary man-and-monster we have a dandy and violent youth in a tweed jacket fighting patriarchal threats and his own repression, while the victims here are not the aforementioned tightly corseted maidens at the mercy of a lustful monster but a group of precocious, emotionally starved children living in a bunker. Finally, the good-defeats-evil ending seen in Hammer's more popular stock has here been subverted to something far more bleak and nihilistic in keeping with the zeitgeist (though it should be pointed out that by the time The Damned was finally released, such concerns had to some degree become nugatory.) That The Damned recapitulates concerns of the 1950s and 1960s at all is down to Losey's political astuteness and penchant for social commentary. Cold War paranoia, the Cuban Missile Crisis, clandestine governments experimenting with nuclear power and disaffected youth are all touched on here just as Losey had touched on the increasingly diffuse class system of the 1960s in The Servant (1963) and capital punishment in Time Without Pity (1957). While in his first British film, The Sleeping Tiger (1954), a young thug is experimented on by a psychiatrist who attempts to 'cure' him of his violent ways; a progenitor of sorts to A Clockwork Orange's Alex. Troubled youth is encapsulated in one line in particular as one of the military men barks to young gang member Ted "Your sort don't have any rights," reflecting the stifling patriarchal rule and lack of freedom of the 1950s and early 1960s that would give rise to the angry- young-men of the same period, and it is perhaps no coincidence that Hammer were keen to make a more contemporary film grounded in realism at this time. Violent, youthful rebellion is the first thing the camera shows us where The Damned begins in Losey's typical style of exposition (sound and action with no dialogue) as the teddy boys orchestrate with military precision the mugging and gang-beating of Simon Wells, a middle-aged American tourist, by using a honey-trap in the form of gang leader King's sensual but subjugated sister, Joanie. Recovering in a hotel lobby a battered and bruised Simon prophetically remarks that he did not expect such senseless and asinine violence to be present England; an issue that should resonate today with socially conscious audiences and those with an interest in the 'hoodie-horror' sub-genre.