jrd_73

The Color of Pomegranates looks great. Director Sergei Parajanov films textures so they pop out of the screen as much as two dimensional images can. This film's strengths are first and foremost visual. There is not much of a story in a traditional sense, nor is Parajanov interested in providing one. Whether this is a problem depends on whether the individual viewer is receptive to Parajanov's intent. The film follows the life of one man. We begin with this boy as a curious, young man in an Armenian village whose primary business involves mats (dyeing, washing, and hanging them). From there, the boy becomes a young man and joins a group of performers. The young man mimes his roles for an unseen audience. Next, our protagonist is older, in his thirties, and living in a monastery. He does much of the physical work at the monastery, but this viewer remained uncertain if the character was actually a priest. Finally, the man is older still (in his fifties), still residing at the monastery yet remaining distant from the other residents. He mostly wonders around outside, much as he did as an imaginative boy in the film's first section. This man is supposed to be an Armenian poet, but he is never shown writing. However, the film often transitions between sequences with a few poetic lines, which one assumes belong to the protagonist, it is not always clear how the verse applies to the images. That brings up back to the images. The film contains some eye popping ones. My personal favorite is in the first section, when as a boy, the protagonist climbs up to a roof to read a large book. On the roof and the adjourning slanted roofs are dozens of open books apparently drying. The image conjures up something magical about the printed word, books as sacred items.

I have watched The Color of Pomegranates twice over a period of seventeen years. I have admired, and liked, it both times, yet I am still not quite converted to its greatness. I don't understand much of the film. This might be on account of my utter ignorance of Armenian history and folklore. Also, I tend to prefer my images in the context of a film with more of a narrative (Eraserhead, Orpheus, Stalker). This second reason may be why I prefer Sergei Parajanov's earlier film Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors to this one. Regardless, every film fan should watch The Color of Pomegranates once. I will probably return to the film again at some point. Maybe then I will find the film to be the masterpiece of cinema that I have read.

Eumenides_0

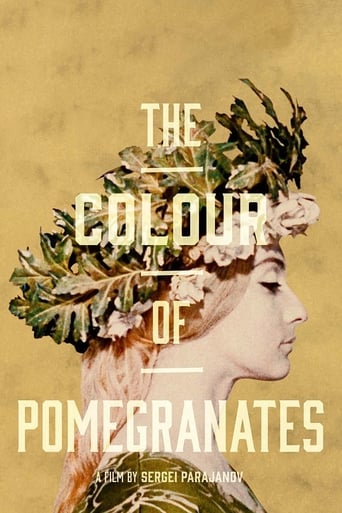

How to portray the life of a poet on film without using traditional cinematic language? Armenian director Sergei Parajanov must have posed this question when he set out to adapt to the big screen the life of poet, national hero and martyr Sayat Nova. To say that The Colour of Pomegranates rejects linear storytelling would be an understatement. To say that it employs non-linear storytelling would be a compliment. I think it is more accurate to say this movie doesn't care about storytelling at all. Finding inspiration in the language of painting, Parajanov turns the life of one man into a series of tableaux vivants.The movie covers the life of the poet from childhood to death in a monastery, but biographical information is irrelevant. This abstract movie shows his life through the things that surround him - clothes and rituals, the religion, the art, the literature of his country, his family, his poetic muse; the objects and colours and people that left an impression on his imagination. There is no conflict, no goal, no moral, just a life illustrated by symbolic living pictures, each one shot by a static camera.Many good movies enthral audiences with greater-than-life characters, byzantine plots or catchy, quotable dialogues. But what is the beauty of The Colour of Pomegranates? The beauty of the movie lies in watching a boy lying surrounded by wet books as they dry on the sun, their pages fluttering with the wind. It's the beauty of highly-stylised human figures performing repetitive and hypnotic movements in strange rituals. It's the scenic beauty of how objects are placed in a landscape or in a room, how they move, how they interact with human figures; of how a costume looks on a human body or how colours are distributed across the screen to achieve harmony.Movies like The Colour of Pomegranates are the reason mass audiences despise art movies: cryptic, frustrating, slow paced, boring. Why would anyone want to watch a movie that requires a reasonable knowledge of Armenian history to merely understand its basic premise? And why would anyone then care to enjoy what they've understood from it? And yet it is movies like this that push forward the art of cinema. Many movies exist that make little use of the possibilities of the film medium. So many use the same medium shots, the same dramatic use of music at the right moment, and nowadays the same teal and orange colours. Most movies at the end of the day aren't more than 19th century novels with movement (most are even adaptations). When cinema language, the language that makes cinema distinct from other art forms, is used, when long takes, wide takes or extreme close-ups are used, filmmakers are accused of pretentiousness. But why bother making a movie that doesn't do what only a movie can do? Well, The Colour of Pomegranates does what only a movie can do. It couldn't exist outside cinema. Released in 1968, in the same year 2001: A Space Odyssey blew the minds of mainstream audiences, Parajanov makes Kubrick's masterpiece look conventional. This movie should be studied the way Eisenstein and Hitchcock's movies are today. It should have changed cinema. Unfortunately, whereas Kubrick had the freedom to distribute his movie, Parajanov's movie was being re-cut, censored and banned by Soviet authorities, which contributed to making it practically unknown to many viewers who'd love watching it. Although an integral version has been available for some decades now, this movie is still looking for an audience. And when it finds one, cinema may change forever.

Barbara

I now know what it feels like being insane. If my life and perceptions were close to this, I would wish for death. I like surrealism, but could not stomach this. It was pure torture and grief and by the end I was weary. If the purpose of cinema was to bore, torture and wear you out, this would be the king of films. If there are people coming over who you want to get rid of, I guarantee the effectiveness of this movie. Why the nails-on-a-chalkboard music alone made me want to poke out my ears. My only consolation was that odor has not been built into movies.Like beating you head against a wall, it is so wonderful when it is over.Enjoy Chis

shusei

Almost everybody talks about the film's beauty and the difficulty of its understanding. It's true. But the difficulty is not from the director's pretension or other shortcomings. When this film was first released in Soviet Union, it was shown in third-rated theaters and with limited number of prints. It was not an original version of Sergo Parajanov, because it was re-edited by another director(director's version is said to have been lost for ever, after frequent showing in professionals' circle). The film's title was also changed--"The Color of Pomegranates" was the title which the administrators of USSR's cinema policy selected to deny "biographical" character of the film. In fact, we can see at the very first title that says "This film is not a biographical film about Sayat Nova...". In short, they didn't admit such an extraordinary approach in making a film about historical important persons. Parajanov's artistic intention apparently went too far, ahead of his time. He wanted to identify the classic poet with himself through the magical play of cinematography, multi-layered mirror-like structure made of image and sound. "Sayat Nova"--it's me", wrote the director in his screenplay by his own hand. Soviet censorship may have cut some shots or shortened some episodes, to make meanings and intention,which originally were clear,remain ambiguous. For example, Sayat Nova's anxiety for his Christian homeland threatened by Islamic enemies(this theme is clearly developed in the film's scenario recently published in Russian).Parajanv, an artist indifferent to politic issues, didn't think that religious theme, as well as aesthetic "anomaly", might be very dangerous for Soviet directors after the end of "time of thaw". Thus the film could'n be a full realization of authors's original scenario.Nevertheless,the difficult situation didn't distort the film's concept and vision as a whole. "Sayat Nova" is still brilliant art of work,and, as many masterpieces of Cinema, will overcome Time by its beauty.