makotoshintaro

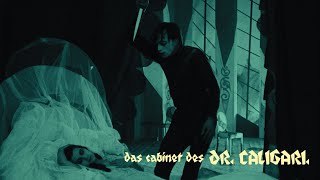

I had tried to watch a silent movie or two before, and didn't actually work out, but this time I think that officially my introduction to silent cinema was more than successful! It is one of the most beautiful depictions of emotional instabilities of human nature. To start with, for me, the Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was one of the most unique films I watched in terms of originality and innovation considering the decade in which it was shot. I can spot a bunch of elements that I've seen in more recent movies, how strongly The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari affected other filmmakers - and not only - around the world. The impact it had upon the goth culture is gigantic. I remember how much I liked the dark, shadowy, oblique landscapes and backgrounds in films such as Coraline or the Nightmare Before Christmas. I was wondering how they came up with it, but it all makes sense now. I could just go on and on praising the light and how those sharp-pointed forms at the back create the best atmosphere ever. The plot twist in the very last 5', something that later directors simply seem to adore, indeed took me by surprise 'cause I was never expecting something like this in a 20's movie. For some reason I had taken for granted that the end would be all sugar coated and rosy but Robert Wiene had something else in mind. By the way, is it just me or has anyone realised that Dr. Caligari wears Mickey Mouse gloves? Or, is actually Mickey Mouse wearing Dr. Caligari gloves...?

JEF7REY HILDNER (StoryArchitect)

I don't like horror, but I show "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" in my film architecture seminar, because the filmmakers hold graphic violence in check, present a good story well told, and conjure a brave visual work of art.Most of all, I like how this silent 1920 surreal thriller illustrates the unity of what I call Form & Story—a concept that helps me design my screenplays and my books, paintings, and buildings.Let me set up my commentary by laying some theoretical groundwork, using terms and concepts I've devised in my practice of architecture.Architecture is a silver coin. Inscribed on one side, FORM: Architecture is the stage set for the drama of life. Inscribed on the other side, STORY: Architecture is a story told through a building. One side emphasizes Aesthetics: architecture as an Abstract Aesthetic System that expresses compositional and physical technique. The other side emphasizes Symbolics: architecture as a Symbolic Image System that expresses intellectual and emotional meaning. Chess offers a helpful analogy. Think of Aesthetics as the system of abstract Moves that chess pieces make when deployed by a chess player, toward the goal of winning the game. Moves like left, right, back, forward, diagonal, slide, jump. Think of Symbolics as the associational Meaning of a set of chess pieces, meaning conveyed mainly by the names of the pieces: a medieval army of warriors (knights and pawns) and counselors (bishops and queen) dedicated to defending the king and to destroying the opposing army and its king. Chess Meaning has nothing to do with the Chess Moves, the strategies and tactics required of a chess player to win the game. So on the one hand, these two systems of chess exist independent of one another. And on the other hand, rather exquisitely, these two systems of chess, Chess Moves (Abstract Aesthetic System: Form) and Chess Meaning (Symbolic Image System: Story), weave together to form a self-referential game, logistical and metaphorical, about war. The complex interplay of the two sides of the Silver Coin of Architecture—the Silver Coin of Art—add up to The Visual: the sum of The Visible + The Invisible . . . stirring within us, ideally, waves of pleasure and insight that reward our twin powers of observation and contemplation. Our desire for beauty and truth.The artistic consciousness that governs Caligari trades in this coin. For example, take the moment at 6:18 into the film, where Alan stands in his attic room, centered in the cinematic frame, pillar-like and pensive, his face the center of visual impact, the book in his hands vying for this honor, our focus then zigzagging (like the zigzag of the room itself) into the picture space, first to the chair and shard of the story-significant bed in the shallow space to Alan's left then to the desk and window in the deep space to his right. Look how the triangle of light on the wall behind Alan diagonals through his left jacket lapel, signaling precisionist control of the architecture of the visual canvas, collapsing character and set into a unified geometric system, integrating figure and field, object and space, man and place, not only spatially and visually, but also emotionally. Alan doesn't stand as an isolated object against a neutral background. He stands enmeshed within the woven fabric of a story-charged background, as much a part of him as his clothes, a man in tension-laced alignment with his well-organized but off-kilter environment, alone in a room that looks physically empty, but feels atmospherically full. Trapped. This introverted book-holding attic dweller, suppressing a recent scare, becomes an extension of the architecture, and the architecture becomes an extension of him. Man and architecture collage together as one. The visible geometry of the Outer Cubism of the Room reflects the invisible anxiety of the Interior Cubism of the Man. The optical architecture of Alan's outer world reflects the emotional architecture of his inner world. And vice versa. Through this device of inner/outer reciprocal reflection, the controlling visual device of director Robert Wiene's suspenseful frame story (written by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, art directed by Herman Warm, Walter Reiman, and Walter Rohrig), architecture is an exterior expression of interior cogitation, a counterpoint to the ordinary take on architecture as "form follows function." The form of Caligari's architecture does follow its function, but this function has less to do with physical construction and more to do with psychological projection. And mood.In Caligari, architecture not only presents the stage set for the drama of life, architecture externalizes the drama of life. On the chess board of Alan's room—within the carefully arranged chess-board space of his weird world of light and dark (and wall with a giant rotated black square)—the White Knight of Aesthetics and the Black Knight of Symbolics assert their coequal presence, blending into a shining Gray Knight of Visual Storytelling: what I dub the Silver Knight of Form & Story. Caligari's unified Abstract Aesthetic System and Symbolic Image System create the Meaningful Form of Alan's eccentric home: a sepia-toned arena of inner and outer conflict, menaced by shadows and foreshadows, contorted by currents and undercurrents that flow from the eerie and mysterious Story in which Alan plays a pawn. What a difference a room makes, jagged, barren, spooky, alive, and dead. Welcome to Caligari's Cubist Knightmares. Where German Expressionism suffuses Cubism with a dark vibe. Welcome to the terribly beautiful architecture of Caligari's Form & Story. A strange, poetic landscape that unspools, ultimately, from the inner movie reel of the story architects' imagination. Enter, if you dare, for 77 minutes, Caligari's spellbinding Cubist Chambers of the Silver Knight.© Copyright 2017 by JEF7REY HILDNER

peytone

As a young adult, most would be surprised that I watch classic films. Since it is October, I decided to check out The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a film I had heard much about while researching classic horror. Many consider this to be the first true horror film, and its influence can be seen in films like Frankenstein (1931).This genre-influencer is about a carnival trickster named Caligari who shows off a somnambulist (sleepwalker) named Cesare at a fair one day, and magically wakes him up. Creepily portrayed by Werner Krauss, the doctor seems to know nothing about a series of murders that suspiciously occur in the town while he is there. Mystery ensues as the protagonists (whose names I can't remember even though I watched this less than 30 min ago) try to figure out who Caligari really is.Being familiar with silent movies, I was prepared for a bit of slowness. This is usually something I can deal with, but I did not like how slowly the intertitles scrolled and how long the takes lasted. The pace was uneven a bit because of this. I found the plot very predictable, especially the fact that Cesare is the murderer, because the shadow in the wall during the murder scene is clearly him. The filmmakers try to fool us by having our heroes arrest an actual murderer, but to me it was an obvious red herring. However, the twist ending (which I will not spoil here) genuinely surprised me and left me glad to have finished watching the film.The sets in this film rely on the German expressionist art movement. They are a bit jarring to look at at first, and are noticeably fake, but I got used to seeing them as the film progressed.The performances by Krauss and a young Conrad Veidt (whom you may remember from Casablanca) are very good. The main character is also good, though I forget his name.Overall, there are better silent horror flicks out there. I would recommend Nosferatu (1922) or The Phantom of the Opera (1925) rather than this film, especially Nosferatu, which is still chilling to watch. Caligari, I feel, has lost a bit of its remarkability in the 96 years since its release, probably because it influenced many other classic horror motifs and tropes which appeared in films like the Universal Monster movies, of which I have been a longtime fan. People who may watch this film will come across elements that are now cliché. Only watch this one if you really want to; the ending makes it worth viewing for horror buffs, but be prepared for a slow ride towards it.

Jamie Ward

Between the varying and conflicting production testimonies of its many players, the endless bizarre legends and anecdotes serving as catalysts for various design and creative choices; between all this there is a small, independent, seminal art-house movie that premiered in 1920 to resounding accolades, praise and most importantly for all involved, money. It was a success that surprised most of the people involved, but looking back at Caligari almost a century forward, it's easy to see how the film was at first universally adopted as revolutionary, and then analysed to death by scholars over the coming decades to the point where the actual film—that is, as a work of interpretive art and not something that desperately requires classification and resolute distinction in terms of motivations, political ideology, historical placement, influence and social stature —is often overshadowed by its lasting legacy as something more than just that.Rather than drive myself to madness attempting to unwrap the mystery of Janowitz, Mayer and Wiene's unending battle of dispute over who did what and why and where, I instead prefer to see Cabinet for what it is; a deceptively straight-forward murder-mystery that exists in a world of irregular angles and avant-garde design. And I'm not just referring to the movie's expressionist scenery which is, of course, what makes the most immediate impression on a first viewing. I'm also alluding to the twisted, dream-like state in which the characters move within their world, almost as if they were one in the same. You could argue, in fact, that they are cut from the same piece of cloth that never wants to settle down in a neat little arrangement until you wish to make use of it. Instead, both the characters and the world in Caligari demand your immediate attention from the very beginning and in a strange way it's hard to draw your attention elsewhere, even if everything does seem a bit otherworldly, strange and abstract.If you're looking for some sort of synopsis from this review, then best leave now. It's a relatively simple affair as I pointed out before, but even then there are many differing interpretations. My own is not in fact my own. Others share it, and it's relevant to us as individuals who see the movie the way we do, but the details of such a view aren't important to you as someone who—potentially—hasn't seen the film yet. Anyone else who has already seen it, more than likely already knows, or doesn't care. What is important, is simply the distinction that exists between Caligari and many films that came before it. It's open-ended, open to debate and, once more, refuses to be consolidated merely to straight, perpendicular angles with only one logical conclusion. This aspect, along with the overall style, atmosphere and artistic merit of the feature is what makes it special. On paper, it's nothing special, and by no means do I loft it as highly as other film historians, scholars or enthusiasts. Let me be clear. I'm not one to automatically prescribe "genius" to trailblazing films ahead of their time for that fact alone. Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a great film, and an extremely important and influential one for sure. But it's not the pinnacle of the movement it begins. It's not perfect, and no, I don't believe it to be a masterpiece. Masterpieces are timeless, and while it's very easy to watch and enjoy Caligari a century on, it's still mostly important because of the time in which it was produced. Again, it's a simple affair. Simple, but extremely effective. So much so that it caused a cinematic revolution, the echoes of which we still hear today.