JohnHowardReid

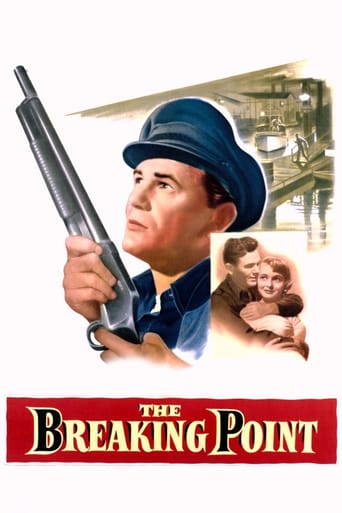

Copyright 15 September 1950 by Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc. A Warner Bros.—First National picture. New York release at the Strand: 6 October 1950. U.S. release: 30 September 1950. U.K release: December 1950. Australian release: 6 June 1952. 8,789 feet. 97½ minutes.SYNOPSIS: An ex-G.I. attempts to make a living by chartering his fishing boat. NOTES: Domestic gross: approximately $1,100,000.COMMENT: Previously filmed as "To Have and Have Not: by Howard Hawks in 1945, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall; and the climax was used by John Huston in "Key Largo" (1948) also starring Bogart. The novel was remade in 1958 by Don Siegel with Audio Murphy in the Garfield part and Eddie Albert as Hannagan under the title, "The Gun Runners".Garfield's second-last film was one of the most memorable roles of his career. Comparisons with the Bogart interpretation in both To Have and Have Not and Key Largo are inevitable, but Garfield's embattled, realistic performance stays with the viewer long after the Bogart charisma is forgotten. Julie can hold his own even against Pat Neal, who is given all the sharp, caustic lines, all the make-up, glances and nuances of the glamorous femme fatale. Such is the power of his performance, he can even make his rejection of Pat in favor of plain Phyllis sympathetic and believable.The support cast is likewise excellent, Neal has a field day with the siren role, Thaxter is not afraid to look plain, even ugly as the harassed wife. Even the two kids quarrelsome and demanding, are far from the usual Hollywood butter-and-spice stereotypes. Wallace Ford turns in one of the most showy of his greasy performances as a shady lawyer, while Hernandez plays Garfield's too-loyal mate with his usual dignity."The Breaking Point" re-unites Ranald MacDougall, one of the scriptwriters of Mildred Pierce, with the producer of that film, Jerry Wald, and its director, Michael Curtiz. The taut, realistic dialogue and violent action are in expert hands — realized against stunningly-photographed locations and atmospherically-lit studio interiors. Curtiz's mastery of the film medium — his tight, deep-focus compositions re-enforce the drama and the feeling of the central character's inner torment and sense of persecution; his insistence on realism makes the explosive climax even more horrible and terrifying; while his ability to draw strong performances is self- evident — allied with an expansive budget and a tight, sharp script — is chiefly responsible for The Breaking Point's deserved reputation as the best screen version of Hemingway. In all, a totally entertaining film, with riveting performances, crackling dialogue, a powerful climax and a memorable conclusion as the crowd is cleared away from the wharf, and Joseph (Hernandez's real- life son) stands, puzzled and bewildered, alone!

SGT Lee Bartoletti

SPOILERS-- Based on Hemingway's To Have and Have Not, the story was first brought to the screen in 1944 starring Bogart and Bacall, and was partially adapted for Key Largo (1948), again with Bogart and Bacall. This version has not been as available as other Garfield films, but finally has re-surfaced. It is much closer to the novel, than the '44 version, although the latter is an excellent film, largely due to the two leads. In this version, Garfield plays a WWII Navy vet who only knows how to do one thing well, and that is be a skipper. He desperately loves his plain, but faithful wife, and adores his two small girls, but is frustrated with his inability to provide for them adequately chartering his boat to tourists. He sort of gets involved with "good-time girl" Neal, and additionally, through the machinations of crooked attorney Ford, with transporting some illegal Chinese immigrants (resulting in Garfield killing a middle man who pulls a gun on him), as well as some gangsters who rob a race track and need someone's boat to help them escape. Caught in a moral dilemma, Garfield's character attempts to redeem himself by overpowering the gangsters and receiving the reward money, but it doesn't quite end like he planned. (The scene where Garfield's shipmate, Juano Hernandez, in a very smooth performance, gets gunned down by a gangster, is sudden and vicious enough to jolt one's nerves.) The second-to-last scene with Garfield and Thaxton, as the latter tries to convince her husband that his shot-up arm needs to be amputated or he will die, is a high point in both of their careers. (A shame that Garfield would be pass away in less than two years after the film's release, the victim of blacklisting.) And in an unusual ending motif, the last we see is a slow tracking shot of Hernandez' little boy, waiting at the docks for the father who will never come back...8 out of 10*s.

kenkopp

Having just seen the Scorsese-restored print of this film at Noir City 10 in San Francisco, I was struck by several things; Garfield's portrayal of a veteran caught up in a terminally narrow view of his own masculinity, Patricia Neal's over the top sensuality contrasted to Thaxter's mousy but devoted wife; and the unbelievably poignant ending along with the unusual treatment of race throughout.The relationship between Juano Hernandez' Wesley and Garfield's Harry is about as race neutral as it could be. Yes, the white guy is the "boss", but he IS the boss, and the fact that his subordinate is black is not at all made into an explicit comment beyond the fact that the reverse would, of course, have been unthinkable in a movie of this time (or even, for the most part, in our own time.) But the fact is they are partners - and they seem truly friends beyond their business relationship. All seems quite "natural". There is an odd scene when Wesley brings his son (apparently Hernandez' real son) along to Harry's house one morning and Harry's two daughters take him off to school with them where it certainly seems that the kids have never met each other before although their fathers have worked together for (we find out later) is 12 years - indeed since before any of the kids were born. Perhaps Joseph (the little boy) is just shy and although he has met the girls before he is reluctant to say hi to them; perhaps this is indeed a reflection of a race-relation-induced reticence on his part, which would not at all be unreasonable.In any case (and here come the spoilers), when Wesley is ultimately shot and then unceremoniously tossed overboard near the film's violent climax we see that Harry is completely devastated; so much so that he hatches an even more desperate reckoning with the "men from St Louis" than he had already been anticipating. Indeed, he seems at that point to be content to die if that is what it takes to avenge his friend; he simply had not considered that this might be the cost of his scheme to get out from under his financial troubles – that someone else would have to pay a price for his problems. Harry dispatches all the bad guys, and is shot up so badly he must be carried off the boat once it is towed back to port by the Coast Guard. This is where the surprising role of race comes in. We see Joseph, Wesley's son, in the crowd at the dock as Harry's wife and daughters are standing in tears, distraught at the prospect of Harry's demise or at the very least the loss of a limb, are shown huddled together, being solicitously taken care of the by the authorities. Harry is put into the ambulance, and the girls and his wife go off to the hospital, too. We see Patricia Neal (with yet another new "captain") and she is allowed to comment on the proceedings. And then we see a shot from above, showing the dock as the police clear the crowd away and tell everyone to go home until the only person left is little Joseph, whom no one paid any attention to, and who is looking forlornly at the boat, waiting for his father to come ashore. The camera holds this shot, and then the film closes.Here we were just seconds away from being allowed to imagine the ending being about Harry's becoming reconciled to a different version of his own masculinity, one in which is not a tower of independent strength and violent self-sufficiency, even so much as to declare, in a rather different tone than he had earlier, that one is "nothing when you're alone" and telling his wife he needs her and will do whatever she says (when earlier this dialogue had been completely reversed), and even to the extent to letting the docs remove his shattered arm. And then Michael Curtiz makes the focus of all the emotion built up over the last hour and a half not Harry and his problems, but the fate of this little boy, completely neglected by those around him, both those who knew him and the officials who might at least be expected to ask why he is still hanging around. We know that HE is going to have to go home to tell his mother (who we know exists from an earlier interchange between Harry and Wesley) that Wesley is nowhere to be found…I don't think I have seen a more astonishing, and humanely interesting ending to a film of this type and period. This film bears re-watching and much thought; certainly a lot of thought (and collaboration between Curtiz, Garfield, and Neal) went into it.(It should be noted that there is a fairly rare treatment of Chinese people in this movie as well, both as criminals (human trafficker) and victims (those trafficked) and that this element, too, bears some further consideration; certainly the portrayal of Chinese in the picture is resolutely unsympathetic (and not just in comparison to the treatment of the few black characters) and this is rather surprising given that other films of the period portray them sympathetically as wartime allies and as American citizens and the "Red Chinese" only intervened in the Korean War as the film was being released so that could not have figured into the portrayal of Chinese when the film was actually being shot.)

Neil Doyle

Ernest Hemingway is said to have liked THE BREAKING POINT more than any other film made from one of his stories and it's easy to see why--especially if you compare this to the earlier version, TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. While that film sizzled with their chemistry in the leading roles, the story here is much more compelling and has much more urgency in the telling.Of course, it's always a shame that Hemingway's anti-heroes fail to understand that playing around with crooked gangsters can be detrimental to the health of all concerned, but THE BREAKING POINT makes you sympathize with the character of Harry Morgan that Garfield plays so well. The shady lady in this case is smoothly played by PATRICIA NEAL, whose patrician presence made Garfield inform her (or so we're told by Miss Neal herself): "You know, don't you, you're playing a whore." She tells this amusing anecdote in a documentary called THE JOHN GARFIELD STORY.PHYLLIS THAXTER is the plain wife of boat captain Garfield, who lightens her hair when she gets a load of the woman (Patricia Neal) she suspects her husband is having an affair with. Thaxter gives one of her best performances as the loyal wife struggling to keep her husband straight, away from the gangsters she knows will ruin the lives of their small family. WALLACE FORD is excellent as the shady lawyer willing to take abusive treatment from Garfield as long as he goes along with the crooked schemes he has in mind.The film has a stark film noir quality to the excellent B&W photography and builds to a quietly effective ending after the long shootout that ends the story, an ending that makes the viewer more aware of the consequences of Garfield's stupid decision to conspire with gangsters who shoot his best friend. Michael Curtiz does a superior job of directing.