treywillwest

This feels like the last in an unintended "battle of the sexes" trilogy, along with Viridiana and Tristana, by Bunuel in which the female goes from passive victim to victimizer. Interestingly only the middle film, in which the title lady goes from being abused to a kind of empowered martyrdom, manages not to feel a tad misogynistic. If Viridiana is the most cinematically satisfying, and Tristana the most fully formed narrative, this sign-off from the auteur is my personal favorite. Here, the filmmaker seems less driven by ideology or anti-dogma as by sheer misanthropy. No longer trying to dispel the world of its romantic and spiritual delusions, the maestro now just wants to watch humanity blow itself up. But, like the work of great, angry poets and songwriters, Bunuel makes his hatred of life seem empowering, paradoxically enlivening.

Blake Peterson

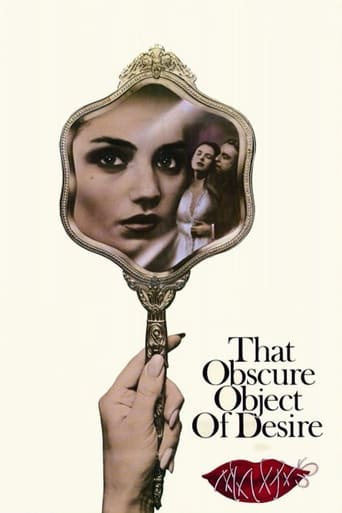

Our obsessions can sometimes get the best of us. Whether it's a piece of art we want to perfect or a person we're dangerously fixated on, as long as you can't grasp your desires with your own two hands, it's as bothersome as a mosquito picking at your arm.Mathieu (Fernando Rey) is having such a dilemma. He is middle-aged, impeccably dressed, and well-mannered. He has been a widower for a few years, and the lifestyle of a lonely, wealthy man has been suiting him well. But that all changes when he meets Conchita, who is hired as a chambermaid. Conchita is 18, sly, and ethereally beautiful; she's played by two different women, Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina. Mathieu wants her, Conchita reciprocates … but she won't sleep with him.When we first catch a glimpse of Mathieu and Conchita's erotic love-hate relationship, they are on the hate side. Mathieu barely misses a train, but once he boards, a young woman chases after him. She dons a black eye, tears awaiting in her eyes. Mathieu tips the conductor, and in return, he receives a bucket, fills it with water, and dumps it onto Conchita's poor, beautiful head. At first, we think she's merely a victim. But there's more than what meets the eye.Once Mathieu finds his seat, the passengers among him stare at him with intense curiosity. After all, the scene they just witnessed was straight out of a telenovela or a Hollywood melodrama. As soon as Mathieu begins to explain himself, we are drifted back into flashbacked storytelling; that's when the film officially begins.That Obscure Object of Desire is Luis Buñuel's final film. Few would choose to explore the themes of sexual frustration as a swan song, but yet again, one of Buñuel's most memorable moments in his long career was when he mock-sliced a woman's eyeball in 1929. Buñuel's odd decision to cast two actresses in the role of Conchita sounds strange in concept but in actuality is a brilliant move. In the more sophisticated, glamorous settings, she is portrayed by Bouquet, who possesses a sort of French New Wave attractiveness that is reminiscent of Catherine Deneuve's famous coldness. In the more hot and heavy, emotionally sarcastic scenes, the buxom Molina takes over, showing Conchita's more fiery, teasing side. But in either situation, Conchita is a both a fixture and a woman of otherworldly dimensions; Bouquet and Molina are superb.Because she is played by two different women, the point Buñuel is trying to make is abundantly clear: Conchita's allure has nothing to do with her looks. Her inaccessibility is what makes her such a catch. Most likely, Mathieu has always gotten everything's he's wanted, from the time he was merely a child. The more he attempts to court Conchita, the stronger his simultaneous hate and passion for her becomes. He buys her expensive gifts. He lets her stay in his luxurious mansion. He pays off her mother's debts. He treats her like a goddess. While she says she loves him and has a clear appreciation of his favors, she simply will not give her body to him. Mathieu doesn't understand. How could he, a man usually treated with such respect, be rejected without any thought? He has bought Conchita everything she could ever want. His torture is both endless and fascinating. He is repulsed but unable to back away; no matter what Conchita does, the fact that Mathieu will never know what's she's like in bed could kill him. It's a shallow thought, yes, but That Obscure Object of Desire provides us with the fact that we don't truly know how much our wants and needs can affect us until it's proved that we can never attain them.Rey gives such a conflicted performance that it's hard not to feel sympathy for him. The premise of the film is so simple, and Rey's dilemma is almost of teenaged ambition; but you can tell that even if his conceptual love of Conchita is stronger than his authentic adoration, the constant rejection is like a slow dosage of poison. She says she loves him, but would someone who loves you really put you through so much pain? Through all of Mathieu's tears, bitterness, and closed off emotions, Rey is a knockout.In one of the final shots of the film, Mathieu and Conchita peer through a shoppe window; inside, a woman is fixing a hole in a piece of bloodied cloth. We take a closer look; the hole has not been formed by an accident — instead, the woman is puncturing a hole, fixing it, puncturing it, fixing it again, and on and on. It mirrors the previous events in That Obscure Object of Desire; the desire grows, is destroyed by Conchita, is renewed, until Conchita destroys it again. Sexual frustration can suck, and That Obscure Object of Desire is a film that tops nearly every final film in any director's filmography.

bobsgrock

The great surrealist director Luis Bunuel's final foray into the exploration of the darkest sides of human desire and will is more straightforward than some of his previous surreal works, especially The Milky Way, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Phantom of Liberty. The other Bunuel film this may most closely resemble is Belle de Jour, which focused on the inner thoughts and obsessions of a bored, frigid Parisian housewife who dabbles in sexual promiscuity. Here, Bunuel dips into literature once again for a tale of obsession told from two, or perhaps three perspectives. The story is fairly simple and straightforward: a wealthy, middle-aged man becomes infatuated with one of his servants, thus beginning a long, torrid relationship between them involving numerous battles of will and determination. The twist Bunuel adds here is the technique of using two actresses to play the same character, the tempestuous Conchita, with each symbolizing her two sides of expression. Angela Molina plays the seductress while Carole Bouquet plays the cold, distant lover. The most interesting aspect of the film from this point is the tug of war these three play. The man wants to fulfill his lust for Conchita in every way, including physical. However, she remains distant, using every opportunity to tease him into submission before harshly rejecting his advances. Her excuse is that she feels going to the next step would lead to him disowning her as he would have done all he could with her. In this way, Bunuel sets up a deliciously comical paradox: both sides have legitimate points to their statements but neither can completely win over the other party.What remains with the audience long after the film is Bunuel's effortless ability to draw in the viewer with tantalizing imagery and ideas. His direction is so subtle, so smooth in its piecing together the story that at times it is hardly noticeable. This was a hallmark of his career, with less emphasis on flashy techniques and more focus on character, story, and thematic development. This final film is no exception and is a wonderful capstone to a memorable career. Bunuel's legacy may be his iconoclastic style, but his insight into humanity's frail holdings on its emotional designs should not, and will not, be overlooked.