theskulI42

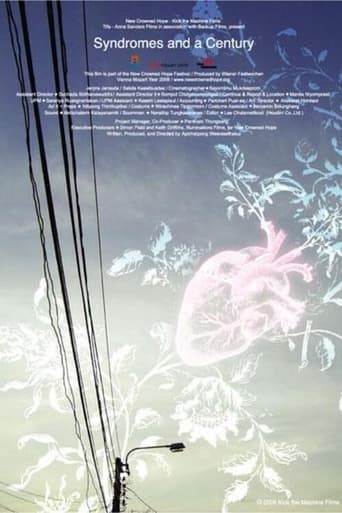

"Normally I sing about teeth and gums, but this album is all love songs" With Syndromes & a Century, Apichatpong Weeresethakul sorta-makes his own version of Tarkovsky's Mirror: a fractured, beautiful, cyclical autobiography in cinema. But Tarkovsky's film was concerned with the whole: inward-facing, but dealing with lost innocence, a desperate search for God and the scope of human existence. Early in on his film, Weeresethakul seems much more interested in the part, the details, the specifics, the ground-level, the things you won't notice unless you stop, look and listen.From the very first shot, the warm, sensual atmosphere present throughout Tropical Malady is all around us again: the weather is impossibly pristine, the sun is shining, the trees are blowing in the breeze, and everyone is speaking in rich, hushed tones. The fact that this section of the film is mined from the mind of the director's childhood at his parents' practice jibes perfectly with what we see on screen: there's a gentle, nostalgic perfection to these scenes; I'm sure this is how every day is when he thinks back, and the camera, like a child, has a tangible presence in the frequent "adult" discussions, but is generally ignored by the subjects of the gaze as a non-entity. It's as if the young Apichatpong had a camera, and now he's looking part at the conversations he witnessed but didn't understand at the time, filtered through the sweet vibe he gets when he looks back.The other unexpected thing apparent right off the bat is how amusing the film is. Weeresethakul is secretly, quite possibly, the most approachable "arthouse" director out there, and one of the initial scenes involves the ostensible lead actress Dr. Toey (Nantarat Sawaddikul) meeting with a chatty monk who relates to her his fear that he has bad chicken-based karma because it comprises a large part of his diet and dreams of breaking chicken's legs, and then tries to hustle her for pain pills. Additionally, the ostensible male lead, Dr. Ple (Arkanae Cherkam) is a dentist-cum-amateur-country-singer, and one of the monks confesses during a cleaning that he once had aspirations to be a DJ and/or comic book store owner (Ple provides the quote at the top) The second half of the film shifts to the present day, transposing the same characters to a stifling, antiseptic modern hospital, and showing the same interactions from a contemporary standpoint: the opening interview between Toey and cheerful medic Dr. Nohng (Jaruchai Iamaram) is much more curt and nitpicky. The monk is advised to cut back on the chicken not because of bad karma, but bad cholesterol, and the brusque doctor immediately attempts to prescribe medication for the monk's "panic disorder". Meanwhile, the dentist and the younger monk's friendly interaction with the sun shining out the window has been replaced by rows of gleaming plastic machinery and absolute silence (to the point that most of the monk's face is covered in an almost-Cronenbergian hood), with the only conversation involved being instructions to open or close the mouth.It becomes quickly apparently that Weeresethakul's picture steers much closer to Tarkovsky than previously anticipated. Drifting into peer Tsai Ming-Liang's wheelhouse, his topic of conversation has become urban alienation; the subsequent loss of spirituality comes a loss of humanity. The key sequence comes around here, when the film cuts between achingly lonesome pans of religious statues neglected in small patches of urban foliage, and Dr. Nohng, on his lunch break, walking with a colleague discussing ringtones and leering at co-eds. The rest of the film runs in this vein: an older female doctor pulls liquor out of a prosthetic leg in preparation for an upcoming television appearance; a chakra healing attempt is angrily swatted away by a young patient who has a large tattoo on his neck and no desire to go to school; an intimate moment between Nohng and his significant other turns into a request for him to move with her to an ugly, high-tech "modern" area of town, and a vulgar gawk at his erection; culminating in a breathtaking sensory overload in the final sequence, wrapping up with a gloriously audacious, discordant series of shots that puts his theme in vivid focus.Social impatience, emotional disconnect, moral malfeasance, all are present in Weeresethakul's view of the present world, but he has done more than scream at the kids to get off his lawn, he's created a treatise on the state of the world: caring is in decline, kindness is in decline, focus is in decline, soul is in decline. I usually roll my eyes when a pundit begins rambling about the "good ol' days", but as a filmmaker, Weeresethakul is tasked with creating his own world, letting us share it, and making us believe it, and with Syndromes & a Century, he's presented us with the trappings of a very familiar modern world, and a hope, a wish, a prayer that maybe, just maybe, by journeying back to his childhood, if not our own, we could carve out a blueprint for how to be a little closer, a little kinder, a little wiser, towards our fellow man.--Grade: 9.5/10 (A)--

johnnyboyz

Thai film Syndromes and a Century manages to come across as an unashamedly routine love story told amongst a palette of long takes, highly ambiguous symbolism, a distinct manipulation of time and space as well as a telling of events from particular perspectives. The film is a high-art piece, with particular avant-garde sensibilities, as it weaves a tale that sways in and out of the past tense, the present tense and distinct and important memories as well as some sort of alternate reality. The film is very spiritual, and it carries that slow and methodical tone that compliments the delicate and somewhat sensitive subject matter of love, rejected love and life. The slow tracking camera as shots of about twenty seconds in length of stone Bhudda statues suggests whatever journeys these characters are on are more spiritual than they are physical.Syndromes and a Century isn't necessarily too concerned with narrative, and whatever development of its characters it does, or connection with them we feel with them, is going to be by way of relating to the fondness they feel for one another more-so the vast and complex changes they undergo. Instead, the film takes a step back; focusing more on camera and atmosphere, in particular, where the camera is situated just as much as it is concerned with where it isn't. There is a scene, very early on, in which the camera stands mere feet off the ground at a door-way and focuses on an individual of medical profession talking to various patients sitting to the side of this person's desk. The placement is pretty clear, and with synopsis in mind that this is a personal piece documenting memories of the director's parents as he spent time in the hospital in which they worked, the shot is quite clearly supposed to resemble a child's point of view; tepid as to whether to come in or not and insignificant enough for the people in the room to pretty much ignore them.But that's not to say the film is entirely told from a child's perspective, just those scenes that director Apichatpong Weerasethakul feels necessary to document in that grounded, lack of cuts and edits manner. Weerasethakul blends a very articulate sense of the observant during most of the internal scenes supposedly revolving around his parents working in respective spaces; shot through a camera that is very much a part of the scenes, but isn't directly involved in the action, with rather routine exchanges and dialogue sequences in which exactly how people feel for one another needs to be laid out and fast-tracked.This romance revolves around a young doctor who happens to be quite fond of what is the closest resemblance in the film of a lead role in a young, female nurse. When this individual eventually confesses his feelings outside in the hospital grounds, there is an entire segment of the film dedicated to a flashback of what I presume to be a prior love in the life of the nurse, a flower salesman by the name of Noom (Pukanok). Given the overall context of the piece and it being a recollection or acknowledgement of past events, the extended break away into the past tense of when the nurse is reminded of prior events fits the overall context of the film; that being as something that is all about delving into the past and remembering important times gone by; times that, indeed, may well have shaped an individual or had such an impact on them that it has made them the way they are.As the film progresses, scenes seem to repeat themselves, but from different angles in the room or at the location. Scenes play out from earlier on but cross the line and have the child-like perspective from a different position in what I can only assume is the director's recollection of the general area he frequented many times but, given how complicated and meaningless everything everybody ever said in these rooms was to a child anyway, a lot of the talk; dialogue and exchanges people engaged in with one another just seemed to blend in with everything else and sound the same. What's important in this regard is remembering how highly the visuals of the piece are emphasised by the director; this is a piece about observing and recalling places and people and how this had an impact on you in your life. What it isn't interested in is any particular aural detail: the dialogue between two people that love one another is deliberately unspectacular and the speech in the hospital comes close to exact repetition.As a piece that evokes a certain emotional response, Syndromes and a Century succeeds. It is a memorable experience about specific memories themselves, while being deliberately ambiguous and hazy in its set time-frame. Even some of the film's more outrageous content feels as if it can carry certain meanings without coming across as too pretentious. Take, for example, the air condition equipment sequence which acts as a visualisation of raw human emotion as the previously seen dust or smoke that had settled in the room is soaked up by a funnel, in a sort of visualisation of the bombshell of a few scenes ago in which a character proposes they move away with their love. The bombshell is dropped; the smoke litters the area but it is then all absorbed as the other individual comes to terms with what positive things that decision may incorporate. The film is stunning at the best of times, which is rather frequently, and doesn't really drop below a level of high, humbling quality.

Cliff Sloane

I have now seen three of Apichatpong's films (Mysterious Objects, Blissfully Yours and now this). It finally occurred to me what is going on and why so many people, already enamored of offbeat, experimental and artsy films, still find his work difficult.I really got into "Mysterious Objects" at first, the "exquisite corpse" method and the way a simple story got embellished as he went along. But Apichatpong seemed to lose interest in the narrative, so the film became a static slide show of his travels, losing all of its narrative energy."Sud Saneha" (Blissfully Yours) never got me engaged. It was an agonizing experience in lost opportunity and self-indulgent amateurism.So now, I can say that "Syndromes and a Century" is by far the best of the three. I gave it 6 out of 10.I finally understood that Apichatpong is an artist of still images. He has no idea what to do with emotions or the people who feel them. He just allows them to populate his canvas, and pays no attention to what they do. In fact, if they do nothing and stay still, that's even better.The camera moves from time to time, but that is clearly just giving better depth to his still images. He has no skills in using images that move, other than to take them in in a decidedly passive way. There are times in this movie when it is effective (the steam entering the pipe, for example), but most of the time, it underscores his discomfort with the moving image.I really want to like his films, mostly because here in Thailand, popular culture is so crushing and stifling, anything artistic is like drops of water in a desert. But I can only cut so much slack.

liehtzu

Pusan Film Festival Reviews 8: Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) Perhaps Apichatpong Weerasethakul's too new to the big leagues to come off as stale, as Tsai Ming-liang does - his films continue to surprise and puzzle. It's hard for me to put my finger on why I didn't like "Syndromes and a Century" as much as I was sure I would, given how enamored I am with "Blissfully Yours" and "Tropical Malady" (the latter is one of the best films of the new century). It probably didn't help that I was running on just a little sleep, the film moved incredibly slowly, and the Korean girl beside me was snoring away by the halfway point. I was expecting more of Weerasethakul's strange, lulling magic, but "Syndromes and a Century" seemed banal compared to the last two films. Still, if there's a film of the festival I'd like to see again immediately - barring Hong Sang-soo's latest - it's this one. From the opening moments you know you're in Weerasethakul territory - a close-up of modest little fellow applying for a rural hospital job as he fields increasingly absurd questions from the female interviewer whose story will be the focus of the film's first half... and after a time a slow camera movement over the balcony to the lush fields and rain forest beyond, and rolling of the credits. The movie's divided into two parts, the first supposedly set in the 1970s and about the director's mother - though you'd glean neither the mother reference or the period setting from watching the film as neither is mentioned, and the setting looks like a rural Thai hospital of the sort you'd find today. A security guard is smitten with the doctor, and she goes on to tell him of a man she may already be in love with, a farmer of rare orchids, and how she met him, in an extended flashback sequence that the director sometimes intentionally confounds with the time period of the telling of the story. The camera drifts around the hospital, where a dentist sings for a monk who at one time wanted to be a disc jockey, and down corridors and along the outside of the hospital, where an ominous low buzzing noise plays over the soundtrack as the camera languidly drifts past outside statues. In the second half the setting changes. We're now in a massive, sterile, big-city hospital, and the the rest of the film is about the man. At the start of the split the same interview from the beginning repeats itself, though the office and clothing worn by the two is different and there are slight but notable changes in the dialogue. Now the camera is pointed at the doctor conducting the interview, and this is the last time she will feature prominently in the film. After the interview the camera follows him as he goes about his duties and tries to find spare time for his beautiful girlfriend. Conversations recur, but again there are differences in the setting and dialogue. The man sneaks into a room in the basement with his girlfriend (a room used to store prosthetic limbs), followed by a very, very long shot of some kind of ventilation tube sucking smoke out of another room, and finally an outdoor dance aerobics sequence with peppy music. What this all means is anyone's guess. Few filmmakers achieve Weerasethakul's mastery of the medium and its possibilities after so few films. He knows how to convey a sense of unease and menace through banal actions or images, and he has a singular way of continuing to fold over what little narrative exists in his films until he has an unusual type of origami, the meaning or possible meanings of which the viewer is left to mull over while scratching his or her head upon exiting the theater. "Syndromes and a Century" seemed a little too plain while I watched it, yet I can't help chuckling now and then or stopping midway through a sentence to contemplate it while writing about it. Ingmar Bergman once made a remarkable comment about Andrei Tarkovsky, that Tarkovsky had opened a door to "a room I had always wanted to enter and where he was moving freely and fully at ease." Apichatpong Weerasethakul isn't a Tarkovsky, but he is opening doors; "Syndromes" sticks to the mind in weird ways.