g0b0

I watched this movie only because David Suchet was in it. I have followed his career for the past 7 years or so. It is frustrating to find anything beyond the 'Poirot' series with his name in the credits. I am not here to analyze the story but David Suchet's contribution to the overall success of the film.According to his website, Sir Laurence Olivier was Sir John Gielgud's mentor in acting. Sir John Gielgud was David Suchet's mentor. That means that from a thespian genealogy, there is a relationship between Olivier and Suchet. In this film, I realized why Suchet's talent for years has mesmerized me. His performance reminded me of Laurence Olivier in his powerful quietness. He evoked such angst and emotion without any outburst, tears or flailing of arms. He said volumes silently through quiet eyes. I simply felt like I was watching Olivier performing in Suchet's skin. I have seen this briefly in other films but never so unleashed as in 'Sunday'. This was the right script and the right director for David Suchet's talents. It was not a perfect script. It may not be the best film but it was a good script and a talented director. I know because I got to see a brilliant actor shine.I found the movie a bit difficult to follow but attributed that to artistic style. Every author and director has their inclination and desire to make their own voice heard. I can accept that and suspend my own sense of disbelief, at least for a couple of hours. After all, it was for the performance of the lead actor I had settled in.

mlraymond

I've seen this movie a number of times, and it still has the ability to raise questions and provoke discussions for me. There are so many possibilities that are never definitively answered. SPOILERS AHEAD: For example, when Madeleine looks at Oliver's wallet, does she find his identification, proving he's not the movie director, and she goes on pretending to believe he is? Why was the supervisor of the homeless shelter so willing to accept the baseless accusations of the others against a man who wasn't there to defend himself? Why does Oliver leave Madeleine looking sad that he's seemingly rejected her, as they were about to make love? Was he just unable to go on with the pretense anymore? And what is the exact relationship between Madeleine and the guy who seems to be her ex-husband? He appears to be living downstairs in the same building, but it wasn't all that clear. The true point is, of course, the fundamental loneliness of human existence, and the need to reach out and make a connection with others, something that Madeleine and Oliver experienced briefly. I feel the seduction scene between the somewhat intoxicated Madeleine, and the slightly less intoxicated Oliver ,is both strange and hilarious. You really don't know where that scene is going for a while. At first, I thought she was being cruel,and really putting him down, as she was obviously taken aback by the true story he told her. But when she leaned into him and touched her forehead to his ,and claimed, in a goofy dramatic voice, that she had drugged his drink with something that would turn him into a potted plant, as she had done with her other victims, and he grabbed her and began kissing her, leading to the staircase seduction, with them mostly dressed ,and she on top, I realized I'd seen something truly original. Recommended for viewers who enjoy a slow, thoughtful kind of movie, that makes you think a lot about apparently small stuff that's actually pretty important in our lives.

bencharif

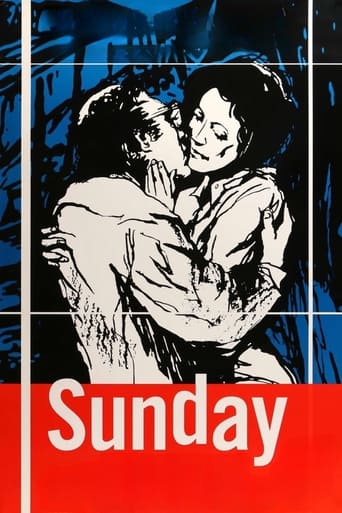

The film's gritty outer-borough images of Queens, familiar to any born and bred New Yorker, got my attention instantly. But it was the film's two principal characters--both middle-aged, both survivors of difficult lives--that sustained it. He, an out-of-work middle management type, is a victim of corporate downsizing now living in a homeless shelter among a multiethnic, multiracial horde of down-and-outers, where he struggles to maintain bare-minimum standards of privacy and personal hygiene--and where remnants of his middle-class life set him apart from his surroundings. She, a faded beauty and still-struggling actress, maintains an oddly genteel life in a rundown two-family house nearby, surrounded by weedy lots and shuttered factories. As they meet and proceed to remove their masks, a kind of love story--brief, impossible, and ultimately doomed, is ignited. This is a beautifully shot and acted film, and a deeply affecting one.

3.141592

If Queens is truly an `un-place,' then 'Sunday' is an `un-film.' That is to say un-believably magnificent! To give this masterpiece a particular label, would rob this wonderfully imaginative film of the root of its quirky charm.I was not familiar with the work of either David Suchet or Lisa Harrow, though I did recognize the name of the director, Jonathan Nossiter.This delightful and honest film rearranges stereotypical categorizations and societal stigmas by transporting us to the `other side of the glass.' While not in great detail, we are acquainted with each member of the men's shelter, which is the location around which 'Sunday' revolves. Some characters are endearing, such as the Vietnamese man who sings opera tunes to canned music in the subway for change, or Ray, the red-haired chain-smoking man who roams the street looking at women's legs and relentlessly searching for the ultimate porn mag.I believe that this again supports the central theme, which discourages as well as discredits the practice of labeling and stigmatizing. The viewer is forced instead, to get to know the men and appreciate each of them on the basis of their individuality.'Sunday' creatively addresses many issues: shame, regret, pride, and deceit. Suchet's character, the protagonist, Oliver Levy-who may or may not be an alias for the famed film director, Matthew de la Corta-is a disillusioned middle-aged fellow who, by way of an unlikely exchange on the streets if Queens, meets Harrow's Madeleine, a woman of similar age and emotional status. The pretense of their meeting is initially awkward and unusual, if not completely bizarre.However, as the film progresses, a most amazing transformation occurs. Within a mere twelve-hour period, amid large amounts of uncertainty, assumption and tactful execution of the imagination, Madeleine and Matthew become tremendously close. By evening, after a few choice run-ins with Madeleine's estranged (as well as strange) husband, Ben, she and Matthew are seen holding hands in a Queens diner, talking intimately like old friends.The point is finally stated-after having been corroborated by the preceding film-that although the world would like to base our worth on `what we do,' in the sense of corporate achievement, the true quality of a person lies, rather, in who we think we are. The way in which we are perceived and subsequently accepted by the people who love us and believe in our potential to succeed, is far more instrumental in our pursuit of fulfillment.Life, inside as well as outside the shelter, is a collection of intricate and unique parts that constitute a whole. Each person has within himself or herself the power to be great, but greatness is subjective. This film proves that love can be found anywhere, whether in a shabby diner over the odd Ozarta, or while walking back from a subway lugging a large house plant.'Sunday' gloriously shows us that whether ones glasses are on or off, it is not with the eyes, but with the heart that we can clearly see the wondrous spectacle of true love.