mark.waltz

Not one man, not even one group or organization, should have access to so much power that could destroy an entire city. That is the plot of this early cold war thriller of nuclear power threatened to blow up London by a disillusioned professor. This intense nail-biting clock ticker is just what the doctor ordered to warn audiences of what could happen, and ironically is what has happened. This is terrorism at its scariest before the word "terrorist" was a frequently used word in our vocabulary, because the culprit is threatening to destroy their own countrymen. Sound familiar?Real time photography of Londoners going about their daily tasks is interspersed with the filmed drama, adding much tension to the already frightening theme. The story intersperses the quest to find the bomb and defuse it before its too late, evacuate the entire city (an empty London is a scary looking London!), and the personal dramas of those involved, including the professor's own family.The dramatic structure is aided by an excellent screenplay, crisp photography and an appropriately tense musical score. The cast of excellent British actors seem so natural in their performances that they seem not to be acting, but reacting to the horrors of the story which they are dramatizing. Particularly excellent are Barry Jones as the nervous professor and Joan Hickson as the flirtatious landlady who rents a room to him and becomes an unwilling participant in his quest for mass destruction.

Roger Burke

I could be wrong but I think this movie, which I saw when it appeared at local cinemas in 1951, was the very first serious production about the possibility of lone-wolf nuclear terrorism. These days, we probably get a new spin on that concept almost every year at the cinema.So, this film is distinctive for that and many other reasons, not the least of which is the semi-documentary style of the narrative which shows, in exquisite detail, the preparations required to evacuate a modern metropolis in the face of nuclear threat. Obviously, the co-operation of the entire city of London was needed to put it all on film.The title, moreover, is distinctive in that it reverses the biblical myth of the creation of the world in seven days. In this story, the antagonist – an emotionally disturbed nuclear scientist – is dead set upon destroying his world in seven days.It's distinctive also in that it takes us into the mind of the said deranged scientist, Professor Willingdon (Barry Jones), showing how he thinks and how he cleverly evades detection from authorities by his local knowledge, his demeanor with people he meets and by taking advantage of opportunities as they arise. So, it's a lesson in the art of remaining on the run to do your worst.The Boulting brothers use all the best tricks of shadow, low lighting, narrow streets and darkness to great effect. Incidentally, not only are some of the Boulting camera techniques up and down staircases vaguely reminiscent of how Hitchcock used the Bate's staircase in Psycho (1960), but also the introductory, frenetically paced sound track at the start of SDTN certainly caused me an "Ah-ha!" moment when I recalled the opening sound track of Psycho. There is, after all, no greater flattery than copying...Finally, the movie is well-paced over all, with just the appropriate amount of light relief occasionally; most of the time, though, the plot proceeds at a relentless pace as befits an excellent thriller, keeping the viewer glued to the screen. However, it's all done with superb British aplomb and without the need for car chases, crashes, shootings (there is only one shooting) and such like. Along the way, of course, we are given the benefit of the writer's opinions – through the script of course – about nuclear war, nuclear proliferation, the Cold War, national security and so forth; one must expect it, given the times when the film was made.The cast is uniformly good, even excellent, especially Barry Jones. Not to be ignored is Andre Morrell as Special Branch Supt. Folland, a cool, perfect foil to the emotionally troubled Willingdon. Watch for a young – and thin – Geoffrey Keen as a patron in a pub. Special mention goes to Olive Sloane as Goldie who unwittingly becomes Willingdon's companion during his efforts to evade capture. Significantly, and appropriately, Goldie has the last line of the story when – while sitting on her suitcase in the middle of Westminster Bridge and as the All Clear wails across London – she asks her little dog: "What will we do now?"She, of course, decides to walk back home. Today, we, of course, are still wondering what to do about the twin curses of nuclear bombs and nuclear proliferation.Give this ground-breaking, timeless story eight out of ten. Highly recommended.February 18, 2012.

blanche-2

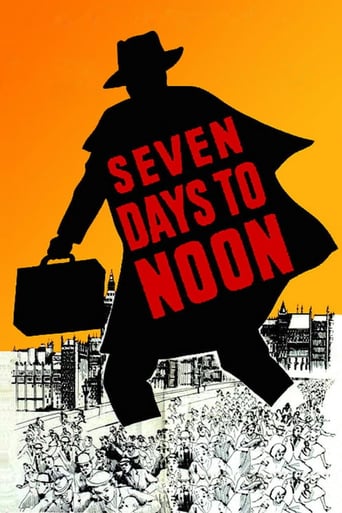

London has "Seven Days to Noon" before it faces destruction in this 1950 cold war film starring Barry Jones, Hugh Lane, Olive Sloane, and Joan Hickson. Jones plays Professor Willingdon, an overwrought scientist whose work in the atomic field has gotten to him; he feels his life's work is being used for evil rather for good. He sends a letter to the Prime Minister warning that if the government doesn't stop making nuclear weapons, he is going to blow up London the following Sunday. Willingdon then disappears from his job and family and hides out in London with an atom bomb in a suitcase.Stories about the possible destruction of humanity are never out of style, and, though low-budget, "Seven Days to Noon" is no exception. Though the end (at least for this viewer) was never in doubt, the film holds interest, with good acting, good pacing, and suspense.Two character actresses are standouts: Olive Sloane as a woman taken hostage by the scientist, and Joan Hickson, known today for playing Miss Marple on Masterpiece Theatre, as a landlady who is suspicious of him. Jones is very good as the disturbed Willingdon.Very good, recommended.

Critical Eye UK

Gawd knows what planet some reviewers here are living on if they think this movie belongs to the sci-fi genre.Of course it doesn't.It's in a league of its own, a 'protest' movie made before CND was thought of and a film with a social conscience long before other UK film-makers had awakened to the realities of the new world (i.e., nuclear era).There's nothing 'sci-fi' in 'Seven Days To Noon' other than the fact that the writers fictionalised the ease with which a nuclear device could be carried around the streets of a city back in 1950. The issues broached by the movie are all too real, and given the way that at this particular moment in history, when the populace at large was still woefully ignorant of nuclear war (remember, both the US and UK Governments consistently denied that anyone ever died of radiation at Hiroshima; it was the blast-effect wot did it, guv) the movie must rank as one of the bravest made by any British studio.Obviously, it has dated. Obviously, the characterisation and dialogue is out of the Ark. But in 1950, we really weren't that long out of the Ark anyway, our collective simplicities pretty well mirrored in the Cockney stereotypes which people the film.Verdict: a lost gem of British film-making -- but never, ever, an example of science fiction.