ElMaruecan82

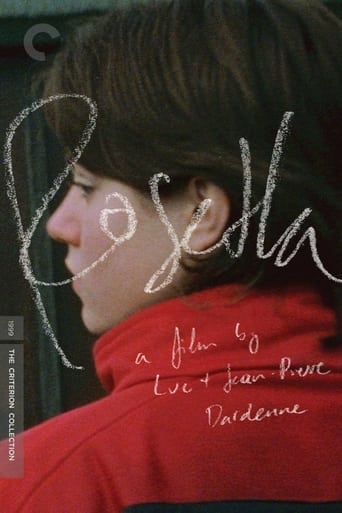

As usual with the Dardenne brothers, there's no time for fancy film-making or cinematic conventions. "Rosetta" opens with the titular 'heroine' walking in her white uniform in some unidentified workplace while the camera follows her, chases her would be most appropriate term as it seems struggling to keep her on frame, while we can hear the loudness of her firm steps indicating that she's either angry or determined. She's both actually.

She's angry to learn that she won't be working anymore, her probationary delay had just ended, angry because she thinks she's been denounced for coming too late by a co-worker (whom she confronts) and determined to keep her job and not let anyone throwing her away. She locks herself in a room but it's only a matter of time before security agents get her out. This is the beginning of "Rosetta", Golden Palm winner of 1999, a unanimous vote, and from the way the first scene plays, we suspect that this ending is only a new beginning.

The Dardennes brothers style of filmmaking is integral to the power of "Rosetta", it can look like pretentious art-house take-the-camera-and-shoot cinema verité but the content is so genuinely powerful that you can't accuse the form. "Rosetta" always walks one step ahead of the camera, we often see her from behind going from one direction to another, this is a young girl struck by poverty and unemployment, living in a trailer park and witnessing the downfall of her mother, prostituting herself for booze. She seems to go in many directions because she can't afford standing still and a job isn't a matter of life and death, but of self-esteem, her mother surrendered, she wouldn't.

But then I make the film sound like delivering an uplifting message about courage and determination, and it would be too misleading. The Dardennes are too aware of the harsh reality of unemployment and poverty to make anything remotely happy emerge from it, perhaps the greatest tragedy of being poor is that it leads to a point where you can't afford even happiness. And Rosetta, played by Emilie Dequenne (she won the Cannes Prize for her performance) rarely smiles, she's suspicious, tacit except when it comes to ask for a job, she's got the will, the determination but Dardennes' movies aren't filmed like melodramas but documentaries, which doesn't diminish their power in terms of pure storytelling.

The film takes off when she finds a job in little Belgian waffle stand, her boss (Olivier Gourmet) warns her about the precariousness of the job, but she learns well and fast. There she meets Riquet (Fabrizio Ringone) who seems genuinely interested in her. Still, if I didn't expect a romance, I didn't expect what would result from their encounter... and what happened was the perfect illustration of the inner ugliness of despair, when you've got nothing to lose and you can drive yourself to any corner. "Rosetta" is a melodrama in the sense that she can't be in love with something, except with the idea of having a job, a steady job and a normal life.

Before sleeping, she recites herself that she finally found a job, this is interesting because we suspect she would never go as far as trading her body, or becoming a criminal. Even the perspective of working illegally doesn't rejoice her, what she wants is to feel normal, like everybody, to be happy, but can she? The extreme where she's driven is perhaps more disturbing than any of these scenarios because it consists of betraying. That's the power of poverty, it can make people act like heroes, victims and sometimes villains. The Dardennes who paint with the brush of truth the uncompromising portrayal of poor people, make us question our own perceptions..

This is not about sentimentalism, this is not about left-wing pathos, Rosetta is pathetic to some aspects, but there's no effort to make her sympathetic, she's just incapable to be happy or give a proper meaning to her life because she's been alienated already, it became symptomatic of her life. The film closes at the moment where we reached that realization and maybe it stops abruptly because it can either take a good or a bad path, but the point is made in this harrowing journey in Belgium, resurrecting the Italian neo-realism. There's something bad Rosetta does in the film but it's as bad what the protagonist does at the end of "Bicycle Thief", we condone it but we understand it.

And I guess the Dardennes don't make film to provide emotional moments but just keep us close enough so we can understand why some people look gloomy, unhappy, suspicious and why they deserve our understanding and ironically enough our distrust. It's sad and cruel, but that's how it is. And again, the directing is part of the film's greatness, it takes us to very uncomfortable and closeted places like the inside of a trailer, a small bathroom, a waffle stands, we all feel like intruders, put in a place that are no cinematically pleasing, but that's the point, the camera goes where Rosetta goes, to places cinema usually ignores.

The Dardennes don't care for the 'look', even if the long take isn't perfect, this isn't Hollywood, within this imperfection, we can sense tension, reality, urgency, despair, struggle and we have a glimpse of these emotions through the documentary style. Conventional filmmaking couldn't have worked for such a story, it had to be as minimalist as if it was embracing the same problems than its character. That's typical of the Dardennes, just like in "The Promise", as if the way they told the story was as inspiring as the story itself or made the same point. Like Italian neo-Realism or like Hitchcock movies, the form sometimes defines the content.

sharky_55

Rosetta, like many of the Dardenne brother's films, opens in medias res, with a young girl confronting an employer about being fired. We are immediately aware of the before and after of these events, and can conclude that this is a regular occurrence for Rosetta, being exploited as cheap labour for a limited period of time, and having to make a loud disgrace of herself when told the unfortunate news. It's impact is so visceral that the film in fact has proved to be the catalyst for reform for youth workers in Belgium.Near home, we see her repeat the same actions over and over; crossing a four laned road, checking the fish traps, refilling her bottle, putting on and taking off her boots and exchanging them for her 'nice' shoes, go all over town in search of a job. These are not exciting in any sense, but you see how it weighs her down, having to return to these tasks over and over to ensure her survival. The Dardennes reused this technique in Two Days One Night, and repeatedly forced Sandra to walk up long pathways, inquire with numerous strangers, and knock and ask the same questions again and again, and build up a sense of dread that came with each refusal. As Rosetta trudges through this day to day cycle, and asks the same questions, we begin to realise that it is not only a matter of financial security, but also her own pride being wounded by every rejection. We see her utter dedication to leave this life even as she is so familiar and efficient in all its facets. Her mother is the opposing force to this; clearly in denial mental issues and whoring herself out for a drink or two. Rosetta hates her, and her mindset that seems so at peace with their destiny of living their lives out in a trailer park, but reacts with the same anger when her mother is clearly being taken advantage of: "My mother's not a whore!" Her last vestiges of pride (throwing food away and refusing to beg or resort to charity) and her tough exterior are eviscerated in one startling scene of vulnerability and emotional distress - while trying to wrestle with her mother and convince her to apply for rehab, she is accidentally pushed into the river. Her mother's immediate reaction is so damning and harsh: she flees like she flees the reality that Rosetta forces her to try and confront. And Rosetta herself, her gruff, defensive voice put on to shield her from any perception of weakness, becomes shrill and desperate as it calls for mommy, to no avail. She meets Riquet, a young waffle worker whom may be the first and only friend in her life. When he rides up to the trailer park, she is supremely embarrassed, but he does not show any signs of ill will or prejudice. He is in fact kind to her, and it is so unexpected for Rosetta that as she lays in his bed at night, she has to repeat to herself or risk falling asleep and never waking up to a 'better life'. She is numb and cold to his open and kind reception; when has this ever lead to something good in her life? And then, as he falls into the water as she once did, she hesitates because it might just open up a spot for her to take. This act is less convincing than revealing his side waffle business to the boss; because we do not see this sort of malice from her at all previously (the fighting at the beginning is more born of desperation), and it feels uncharacteristically cold, even for someone who is looking out for herself. But this lends power to Riquet's final action, because of this hint of hesitation - the Dardennes reverse it and for once in her life she finds a little spot of solace, of compassion, that is so genuinely honest and good, even as Rosetta has done all of those things to him. It is shot in the same way as all of the Dardenne's work, but perhaps because of the subject matter, it is an even more harrowing vision of the neo-realism aesthetic. Long takes and body language are used to depict the heightened senses of Rosetta and how they have been tuned as a result of this lifestyle and to ensure survival; as she picks up on stray dialogue in the background about money being left in a till, as her body stoops in resignation of having to help her drunk mother up again, and in a subtle moment, as she nervously glances off-screen briefly at Riquet, whom has come to the store to survey her in his old position. Sometimes, the physical shaking of the camera does get a bit excessive, and is relied upon rather than the actual desperation of the body and facial expressions. And like always, there is no music to speak of, no sentimental chorus or signalling of moment of change. Just a repeated mantra that is whispered to no one but herself, because if it is not reaffirmed, she may lose hope altogether.

Camoo

Re-watched this film recently out of interest and vague, powerful memories of the lead actress, Emile Dequenne. I was very happy to have revisited it. In the years since seeing it, I have caught up on all the Dardenne brother films, and consider them to be among my favorite directors, observant, gentle, and tuned into a world I personally know very little about. His characters are alien to me - and indeed alienated themselves, though I grew up in Belgium I did not know anybody like Rosetta. The impact of a Dardenne brothers film is very intense, and are often very cathartic. Rosetta is no different. Filmed very sparsely, leaving characters with very little place to hide and ultimately displaying a profound vulnerability. It really belongs among the greatest films.

Tim Kidner

To say that Emilie Dequenne. the young actress playing Rosetta - and who won the Golden Palm at Cannes for her efforts here, is 'plucky', would sound patronising, to say the least.This is structured documentary film-making at its most urgent - and poignant. The premise for most could hardly be less appealing - an independent film, filmed at a moderately sized Belgian industrial town, with an actress who wears no make-up (yes, the odd pimple, too) has an alcoholic mother who gets more booze by offering herself for sex and they both 'inhabit' a tiny, leaky caravan on a caravan park.By plucky, I mean that Rosetta is almost always running - from someone, after someone - including her own mother - to a job, from a job. When not doing that, she gets thrown in a lake (by same person as above), catching fish in said very muddy lake, using a broken glass jar. She is always trying to either get work, keep her job or survive, somehow.This all sounds quite frantic - and it is, when the hand-held camera follows her, is glued to her, almost, as she goes past so close, she briefly goes out of focus. But often, it is meditative, thought- provoking and downright very ordinary. Which, oddly, is extremely compelling, never more so during the gaps in dialogue.Underneath this hardened facade - she only swears and fights when really pressed, then she's like a terrier dog - we hope to see a normal young lady, who can do things that she enjoys. We only see this once, when the young man at the new waffle-van where she finally gets a casual job, takes her after the first day, back to his, for food and playing of some music.If this is SO mundanely glum, why am I watching it for the second time? Well, my Halliwells Film Guide (bible, to me) rated it highly and I got a copy cheap as a Korean import and secondly, you just know that there is a message here. Not necessarily a very important one, but one that we need to reminded of, when we all (and our Governments) continually moan about the youth of today and how they never want to work - and about caring for those unable to care for themselves.It's also very sobering (definitely no pun intended) and one with an ending that you'll remember.