Dr Jacques COULARDEAU

This is a great play with the full music of Shakespearean language, including the music, loud indeed, of historical semantics. But let me BE more to the point.We have here the story of King Richard II, the son of the Black Prince, born in Bordeaux. In the play he starts with grandeur and grandiose pompousness and that is emphasized by costumes that are heavy and huge. Confronted with Bolingbroke's accusations against Thomas Mowbray, duke of Norfolk, and vice versa in some reciprocal verbal vendetta. They agree on an ordeal, in fact a fight to the death like some feudal tournament, the winner is innocent, the other is dead. The king then appears reasonable, and yet he stops the fight just before it starts and banishes the two young men. Mowbray for life and his cousin Bolingbroke for ten years, reduced to six on the appeal from John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and the father of Bolingbroke. Strangely enough the King has two uncles, Edmund of Langley, duke of York, and John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, but no father of course since he died on 1376. Then the king decides to go to Ireland for some expedition, military tourism of the time. On his way he visits John of Gaunt who is dying and dies in front of him and the king reveals his real nature. We know he is slightly tyrannical, definitely nepotistic and extremely vain in his anti-feudal stance against a fight to deliver justice. But after the death of his uncle John of Gaunt he announces that he will seize the whole assets of the man, castle, money, land, along with the chattel (including the serfs of course). He thus dispossesses his cousin who is not present since he has been banished. The king appears there as someone who should retire from power, but in feudal times that was not the normal procedure, and in fact no one could or should even hint at questioning the authority of the King: that was treason and nothing else, a treason totally enforced by the authority of the church, and that is one stake of this play. The king leaves his other uncle Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, as the regent during his absence. We can see the rivalry between the two houses of York and Lancaster, the famous two roses, getting in place and Richard II is vastly responsible for what was going to happen.Back from Ireland he finds himself in front of a rebellion led by Bolingbroke, the duke of Lancaster, who has come back from exile with no permission and who, though dispossessed, has managed to get the nobles on his side and the king has to resign, or abdicate. Shakespeare insists on this abdication and the subsequent coronation, imprisonment and final assassination. It is important to know that such a procedure is not possible: that's why the church is reluctant and the play insists on the fact that he is not dismissed, but he voluntarily abdicates in favor of his cousin Henry. But in the mean time the son of the Duke of York, the duke of Aumerle has been convicted of treason and condemned to death. He is part of some plot involving the church. His mother and father go plead with the king, the new king, Henry IV who yields on this Duke of Aumerle but on none of the other plotters. At this moment we can see the war of the Roses behind, looming up slowly since the King is now a Lancaster and the plotters are around as well as inside the house of York. The pardon to the son will leave the house of York with a direct heir and that pardon was probably a mistake from the Lancaster the king is, but history is full of mistakes.This play has very lyrical moments that are creative reflections on power, the isolation of power, the sadness of power and yet the responsibility of power. Richard II thinks he is power by essence and thus his abdication should physically destroy him, which is not the case. At the same time the rivalry between the two houses is coming up slowly but it is inflamed by the zeal of some courtiers. In this case the assassination of Richard is a direct provocation against the house of York, and at the same time the pardon to the Duke of Aumerle is an act of weakness that does not improve anything. In spite of the dramatic events, and the tragic though slightly melodramatic end, of this play the historical reflection it contains is probably not that clear, not that fully constructed. I mean it is contradictory. The characters are not always conscious they have to accept power and do what the situation requires. Richard II becomes dictatorial with age, which is abuse of power, though he is rather young when he falls, and Henry IV is rather hesitant and lacks determination at the end of the play, at the beginning of his reign, and Shakespeare shows how the clergy and some nobles are plotting in the wings, behind the back of the king. In feudal times a king could only grant his own abdication and he would do this only if ge felt there was a full alliance of the nobles and the church against him: that's at least what happened with Magna Carta.That's Shakespeare's conception of politics: it is always fishing in dark water, maneuvering with no visibility, speculating with no specular mirror or magnifying glass, hence seeing nothing, neither any reflection nor any enlarged picture. This history though does not have any comical scene or character, apart from the scene in some bathing and massaging hall or cellar, the king is having some fun with his "creatures Bushy, Bagot and Green. [...]Dr Jacques COULARDEAU

clivey6

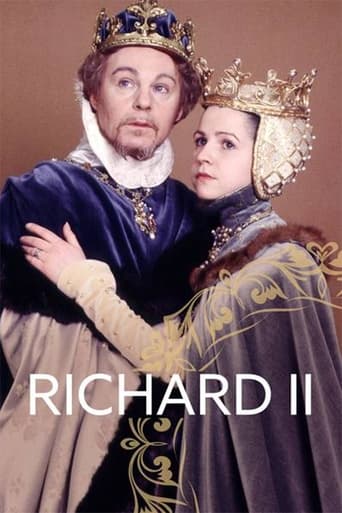

This is great to watch with the subtitles, and it's generally quite comprehensible, whereas reading the Aarden Shakespeare meant I had to consult the notes to figure out what the characters meant.That said, there's more than a touch of camp about Derek Jacobi's titular king, to the point where I wondered if he had a bit of the Edward II about him. Jacobi's effete manner reminded me of another, even earlier king, King John, as played by Claude Rains in The Adventures of Robin Hood. All very good up to a point, but it began to lack a certain range for me. As his self-pitying histrionics rose to a pitch near the end, I began to think of Richard Dreyfus in the 1990s sitcom Gimme Gimme Gimme, and how he might expostulate over some handsome hunk he'd had within his grasp, only to let slip through his fingers like slimy spaghetti in cold water - while an unimpressed, gum-chewing Kathy Burke watches on.It's 2 hrs 40 minutes, btw. Look out for a great supporting cast including Clive Swift (Keeping Up Appearances, Excalibur) among the more obvious names.

tonstant viewer

Richard II is the setup for the cycle of history plays, and as such devotes much time to explication. So it can be a little dry compared with some other Shakespeare, and so it is here.The cast is almost uniformly excellent. Jon Finch is a sturdy Bolingbroke, and Sir John Gielgud is memorable, speaking John of Gaunt's "This England" speech as if no one had ever spoken it before.Charles Gray, usually a "damn-the-torpedos" scene stealer, here defers magnificently to Dame Wendy Hiller. When the two plead on their knees simultaneously for and against a royal pardon of their son, they teeter sublimely on the razor's edge of urgent melodrama and marital farce - an exquisite and very difficult moment.The problem for me is a very intelligent, much praised performer who fails in the title role. Derek Jacobi often makes wise choices as he prepares and analyzes the text. Then he commits the actor's unpardonable sin of monitoring his own performance while delivering it. He winds up admiring his own work while doing it, which in serious drama is disgusting.It is also a truism among actors that either the actor cries or the audience cries, but never both. Unfortunately Mr. Jacobi cries so much there's no reason for us to join in; he sheds enough tears for all of us, and we just sit and stare.The other odd thing about Mr. Jacobi's delivery is his total lack of velocity. It doesn't matter whether he speaks quickly or slowly, loudly or softly, there's no movement, no snap, no impetus, no forward motion. Everything emerges from a thick, suet-y, pudding-like stillness, and he never actually manages to get from point A to point B - compare with Gielgud's performance in the same play, where the older man has lost his long breath, but manages to gallop nonetheless.The BBC videos of Shakespeare's comedies and romances have much more engaging production design than the histories, but what we see here is perfectly adequate, if not arresting.The all-important pacing is uneven, except for the scene of the handing over of the crown, which grinds to a dead halt. This last should have been tightened in the editing. Overall, tedium is not avoided, it's embraced.So if you really think that Derek Jacobi is a great Shakespearian actor, don't mind me, just plunge right in without hesitation.I personally would rather get my hands on a copy of the Shakespeare Recording Society version from the 1960's, starring Sir John Gielgud as Richard II with Michael Hordern, Leo McKern and Keith Michell; this is available on audio cassette in the UK and on CD nowhere, and that's a scandal HarperCollins should address.

frostl

Richard II is one of those plays that hangs almost wholly on the performance of the leading actor. While the action centers on the deposition of a king, the play is not so much a political drama as a psychological one. Shakespeare's interest, and therefore ours, is focused primarily on "unking'd Richard" rather than on his conflict with Henry Bolingbroke, the "silent king." Fortunately, the BBC version gives us a central performance that does the play justice: Derek Jacobi (one of my favorite actors anyway) does a turn here that's nothing short of splendid. Most of Richard's longer speeches have a nearly operatic quality to them, and Jacobi's reading does not disappoint. It's a great portrait of a petulant young king who gains -- if not true wisdom, then magnificent pathos.The deposition scene alone is worth the price of admission. :-)(I now apologize for the pretentious opening. I'm writing a thesis on Richard II at the moment -- indeed, I should be writing it *now* -- so I'm still in literary critic mode... ;-) )Although Jacobi's bravura performance dominates the production, there are a few others that really stand out, chief among them Sir John Gielgud's amazing, intense John of Gaunt (whose last scene is just riveting -- his elegy for England gave me chills), Jon Finch's calculating Bolingbroke, and Charles Gray's York, who fortunately is not played as comic relief.All this praise is not to say there's nothing about the production that doesn't work. For instance, the confusing and allegorical garden scene is rather unimpressive -- it's difficult and stylized anyway, and neither Janet Maw as the Queen nor Jonathan Adams as the head gardener really pulls it off. And the scene where York accuses his son Aumerle of treason while his wife pleads for pardon, rhyming all the while...well, it isn't one of Shakespeare's finest moments, but these actors, to their credit, went a ways toward making it watchable. And then there are the usual quibbles with the BBC production values -- the sets and such are not particularly impressive-looking; it's more like watching a stage production on film. But that doesn't matter if the performances are good -- and for the most part, these are first-rate.