chaos-rampant

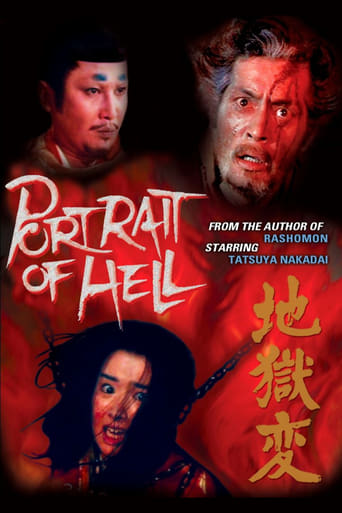

No one does 'descent into madness and despair' better than Tatsuya Nakadai. And when it comes to theatrical lighting, expansive settings, and slow-fi supernatural poetics, no one does them better than the Japanese, who had the benefit of a few centuries of kabuki experience before Mario Bava and Roger Corman got there with their cobwebs and color filters. All the elements are in place then and Shiro Toyoda delivers with utmost impunity. In part a not-so-distant cousin of the kaidan genre of spooky ghost stories that proliferated all through the first half of the 60's in Japan, complete with deformed ghostly apparitions that come and go as they please, yet also a bit of a prestige film that can afford beauty for beauty's sake without having to cram plot points in the short running time of a second-bill film, this reflected in the stars of the film (Tatsuya Nakadai and Kinnosuke Nakamura) and the lush sets Toho Studios put in Toyoda's disposal, the vivid colors and accomplished camera-work that suggest a director more talented than his nonexistent reputation in the West implies, all these elements coming together to create a dramatically unsubtle, not really horrifying but tragic and macabre, parable on the unyielding monomania of a perfectionist. A Korean painter is summoned by his Japanese lord to paint a portrait of Buddhist heaven. The Japanese lord becomes smitten by the painter's daughter and takes her for his concubine. The Korean painter pleads for his daughter, this coming across as more the whim of a possessive father than genuine love. Finally he settles for painting a portrait of hell. You just know Tatsuya Nakadai's face is gonna be a mask of utter despair and torment by the end and it's worth the ride getting there because the conclusion is truly ferocious.

frankgaipa

Though I've seen most of his older stuff, my current impression of Tatsuya Nakadai derives from "Ran," "Kagemusha," and an appearance at Berkeley's PFA. At the latter, he appeared, as Japanese can, stiffly polite, a bit broader of chest than I would have expected, though age brings that, and at least, I think, average height, in an immaculate gray suit. His fluidity of movement in the 1969 "Jigokuhen" startles me even against the early samurai roles. While Kinnosuke Nakamura, playing Lord Hosokawa, embodies in every movement the calm attached to his character's status, Nakadai's never still. Nakamura looms, of course in court, but no less so crouched over Yoshihide's daughter or alone, pacing. Nakadai leans, bobs, treads air, seldom or never freezes. Even in the presence of court women, of anyone but his daughter or her suitor, he seems always the shortest person on screen. Think of Jean-Louis Barrault in Jean Renoir's Jeckle/Hyde film "Le Testament du Docteur Cordelier." As the doctor, Barrault's his true height. As Opale (Hyde) he's a foot shorter. The transformation happens before your eyes, with no special effect, and is absolutely believable. Nakadai here rivals that feat.If "Jigokuhen" were a better film than I think it probably is, I'd elaborate the irony of the Yoshihide's groveling against the Lord's serenity. More startling though, is Yoshihide's lack of humor, against the Lord's embodiment of it. Indeed Lord Hosokawa's the only one in the film to joke, and keeps trying nearly to the end. Yet another case- Milton's Satan certainly wasn't the first-of the bad guy getting most the good lines.

AkuSokuZan

This filmed theatrical performance centers on the tension between a Japanese ruler and a Korean artist. The ruler a Buddhist who considers himself a living Buddha amidst the suffering of his people brought on by his indifference, the artist a Confucian whose pride has been trampled on so many times he comes to hate even his innocent Japanese student who courts his daughter. One of the many themes in this carefully told story includes the idea of individuality portrayed by a political rebel sporting an ogre's mask. The rebel and the Japanese art student, fueled by their individual power, storm the castle of the corrupt lord like demon's of hell. Although the wheel of karma turns, symbolized by the wheels on the lavish royal carriage, their is always personal choice. The artist chose to imprison his daughter,Yoshika, drive away his foreign protege, and dared the lord to burn the carriage holding his girl. The lord chose, to indulge in an egocentric project to have a painting of himself as an enlightened being, verbally and physically abusing the genius painter, ignore the Korean king's call for help during an invasion, hold the innocent daughter of the artist, and ordered the slaughter of Korean immigrant's as they tried to go home. We, the audience hope for a glance at the evolving masterpiece the artist is working on. The painting is at first inspired the the fear of a chained little boy who squirms at the sight of approaching snakes. Finally, the artist (Tatsuya Nakadai) realizes that the torment of damnation is within himself this whole time. The flames in the movie seem to melt the screen and the haunting flute song becomes the soul of this tragedy. All the actors and actresses perform this tale in a very traditional, super dramatic way. Every time the artist begs for the return of his daughter from the lord you can't help but feel heart broken. The film is a real treasure but slightly flawed due to the innapropriate soundtrak which would be more appropriate for a western epic. Masaki Kobayashi's Kwaidan clearly contributed to this film's lush and hyper real colors, textures and images. Do anything you can to view this work.

fuyuno

19 years after Kurosawa's "Rashomon" a very different director took another story by the inimitable writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa and adopted it for a movie. "Jigokuhen" is a more complicated tale than even "Rashomon" and consequently must have been more difficult to film. @Be warned that I am giving away the story.@This is a story of a medieval painter (Nakadai) commissioned to paint the portrait of paradise on the wall of a palace of Lord Hosokawa (Yorozuya) the most powerful aristocrat of the time. (He is powerful enough to name the next emperor.) The nobleman wants the mural to demonstrate the glory of his power. The artist, who unlike the aristocrat sees the squalor of the world just outside of the palace, refuses. He would rather paint a portrait of hell. Confronted by the only man who would dare contradict him, the arrogant nobleman challenges the artist to paint a portrait of hell, on the strength of which he will decide whether paradise or inferno will be painted on his palace walls. The painter is the sort of genius-madman who would cut off his ears to paint a better self-portrait. Obsessed with his art, he goes to great extremes, such as actually torturing his apprentices to capture the expression of agony. In the end, even that is not enough. He wants the nobleman's gold-plated carriage set on fire so he can see what the fate of vanity in hell really looks like. The carriage is a symbol of the nobleman's power and position, but he cannot refuse because he is too proud to backtrack on his promise to provide anything the painter needed. The aristocrat instead puts the painter's daughter (whom he has taken under some pretence as his sex slave) bound in chains inside the vehicle and proceeds to have the carriage dowsed in oil. Then he hands a torch to painter and dares him to set the carriage on fire. The aristocrat is triumphant for only a few seconds. As she burns to her death, the daughter screams "I knew it would end this way!" Some time later, a finished portrait of hell is delivered to the palace. The painter commits suicide the same day and the nobleman, haunted by the ghost of the painter, is driven to madness. Only the brilliant artwork, a picture of hell, remains.This is a treatise on the nature of art and the conflict between the artist and the patron. It is also a story about the pride of an obsessed artist and the hubris of the man who thinks he owns him. A very complicated tale.The movie gets sidetracked by an unnecessary sub-plot involving rebels. Also the prolonged wandering of the painter through famine-ravaged Kyoto could be rather dull if you did not understand that much of the pantomime represent other stories by Akutagawa set in the same period (including Rashomon).Otherwise, this is a great movie and a rich experience to watch.One pet theory of mine is that the garish colors of the films of the 50's and 60's actually helped Japanese cinema. The Caucasian woman is the most beautiful kind of human in a black-and-white movie, which probably helped consolidate their position as the epitome of human beauty. The Japanese, strangely, look very good in the hues of early Technicolor. It may have contributed to the popularity of Japanese films of the era. You will see what I mean when you see this exceptionally beautiful movie.