Framescourer

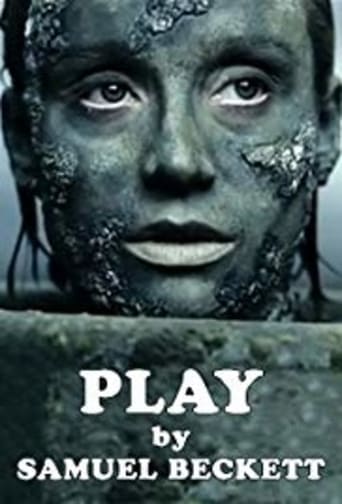

This is a filmed play; one must judge it as such. Minghella's rapid reaction camera takes the place of stage direction for a spotlight. But that's about it. The full 16 minutes (8 mins of script with the instruction to repeat) are played out with little intervention from the director, save cutting or inter-focusing between the three talking heads and mixing head-shot with super-closeup.The three characters live out a collapsing love-triangle. Is it happening now? Are they living over what has already happened? Is this a dramatised overview of what always happens? These are all valid questions as the script is delivered, overlapping, at barely digestible speed. Juliet Stevenson (the mistress) is the most interesting, allowed a full expressive range throughout her role, including a flash-dispatched orgasm. Most hilarious is Rickman's man-at-the-centre (literally as well) who retreats into talk of tea when he's not got the hiccups - an important element, this impediment, as it has the same worth of content given the monotone delivery. Kristin Scott-Thomas' trademark 'disinterest' makes up the trio.I like Minghella's top-n-tail affectation of the rushes cards, which brings into relief the 'play' suggestion of the title. Is this a record of the consequential comeuppance coming for the characters? Or is it simply as valid a circumstance as the next for working out the old rite of cheating relations? 6/10

mcellis-1

This is a brilliant work, and for me the highlight of the Becket on Film Series. "Play" tells of the horror, the purgatory of broken human relationships. Yes it is banal, yes it is repetitive, but that is precisely the point. The menage a trois depicted has trapped each of the three characters in an endless hell, the same thoughts over and over, the same self-justifications, the same loss. No one can hear the others. Mingella brilliantly shows us in cinema what could never be shown on stage, that this pain goes on forever, to the end of life and even into death. In showing the three urns surrounded by hundreds of others, we see everyone else trapped hopelessly within the tyranny of their private griefs. The most challenging, the most arresting short film i have ever seen. Highly recommended.

Matthew Tantony

This, being cutting-edge modern drama, I approached with not a little trepidation when Channel Four started its "Becket on Film" season. I'd already watched the five-minute short "Catastrophe" with John Gielgud and I didn't know what the hell that was on about.For the newcomer, "Play" is bizarre and difficult to get to grips with. Three disembodied heads gabble away incessantly in monotone voices, each relating their own versions of a love triangle while a frantic CCTV camera cuts between them. I applaud Becket's decision to play the story twice, as otherwise I would not have fully appreciated this complex tale.Essentially, "Play" is "Rashomon" at Warp 9. The shaky, noisy camera cuts between the three heads (Kristin Scott Thomas, Alan Rickman and Juliet Stevenson) as they fulfill their punishment to talk about their sins for eternity. It gets more and more frantic,cutting away first in mid-speech, then in mid-sentence, then in mid-word. Then Stevenson starts laughing hysterically. At times the film itself breaks down, as if it has been retrieved from hell itself.At the end of 15 frantic minutes I was left a little confused by the three-layer dialogue. I shall need to watch this a few times, preferably with a script, to pick out the separate narrative strands. However, Minghella's direction was nothing short of sensational. He may have taken liberties with Becket's original text, but the rapid cross-cutting, repetition and the intrusive whir or the camera as it selected its target, made for one of the most breathtaking fifteen minutes of film I have ever had the privilege to see. This will not appeal to everyone, but I recommend it to the more adventurous viewer.

Alice Liddel

'Play' is one of Beckett's most delightful confections, a farce, a vision of hell, a discordant fugue, a logorrheic din: as much a parody of Sartre's 'Huis Clos' as Sunday supplement suburban entanglements.Three heads - a man, wife, and mistress - look out from urns, and relate the story of the man's affair and the wife's reaction to it, in a rhythmic, overlapping gabble, repeated twice to convey the idea of eternity. These lives, brought to crisis point by a very physical interruption - adultery -are condemned to a disembodied, inhuman, mechanical repetition of a previous existence.Here, Beckett's interest in memory is at its most alienated - recalling the past is not an act of retrieval, an attempt to piece fragments of a shattered identity as in, for example 'Krapp's Last Tape'. It is a punishment, devoid of poetry, oppressively banal. Worse, the reminiscences are prompted by an unseen lighting man, like a Gestapo interrogator, switching speedily between characters, creating the play's rhythm, forcing them into 'life'. Much as they might like to, they cannot hide, they are at this man's mercy.You can imagine the effect in the theatre: not only is the mundanity of everyday life shown to be mechanical, barren, dead, with the urns and the repetition not a metaphor for hell or limbo, but for life; but the way these insignificant lives are interrogated, as by the Gestapo, or God, or their own conscience, or paralysed desires, or us, or SOMEBODY, forces us to admit that we don't live very well.Minghella, unlike his 'Beckett on film' collaborators, eschews over-fidelity. He keeps Beckett's words, but is radically unfaithful (a compliment!) to the play, liberated from theatrical constraints. His bombardment of montage; his intrusive use of colour, sound, camera angles; his turning Beckett's lighting man into the camera, with its clicks and whirrs and zooms; all fundamentally destroy Beckett's theatrical space.A condition where hell mirrors suburban life, where immobility , darkness, emptiness, inertia are the tenets, is given an incongruous energy, a visual excitement. Beckett's verbal and lighting rhythms are transformed into those of editing. Life in hell no longer seems that dull and repetitive; neither, by extension, do our own lives. The intrusive, oppressive interrogation of the light becomes the more distanced voyeurism of the camera - it is not this latter that breaks the space but the editing.This is an excellent example of an artist freeing himself from constraints, undermining his text, while remaining superficially faithful. Surely the appropriate response to 'Play' is to play. A very brave adaptation.