catsklgd1

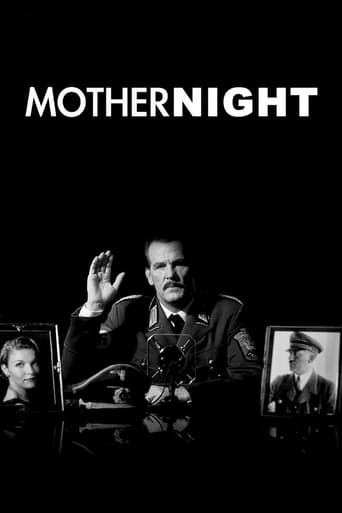

While always a fan of Nick Nolte's, I have been frustrated at times by his choice of roles. However, in his portrayal of Howard W. Campbell, Jr., Mr. Nolte has achieved, perhaps, his finest hour. This adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut's brilliant novel shines the light upon an age-old question: just how responsible for their actions are those who are "only following orders?" I believe Vonnegut supplies the answer in this story. If you're looking for a movie to really sink your teeth into, this is the one. At the time I saw it, I had remarked to my wife that I was tired of the garbage coming out of Hollywood; I'm glad I salvaged this one off the top of the pile - it deserved rescuing.

edwagreen

Screenwriter Howard Campbell is recruited to serve in counter-espionage during World War 11. He moves to Nazi Germany and marries an actress whose family is faithful to their Fatherland. Campbell, portrayed well, by Nick Nolte broadcasts vitriolic propaganda for the Nazi Regime. Truth is that few people really know what Campbell is up to.The war ends and Campbell, with his wife presumed dead, heads to N.Y. for a new unassumed life. Here is where the picture falls apart. After several years, without anyone knowing him, Campbell assumes his real name.At this point, as stated, the film deteriorates into a series of unlikely events. A neighbor turns out to be a Communist spy. who notifies an Aryan supremacy group of Campbell's existence. The latter's dead wife suddenly shows up only to reveal later on that she is the sister of his dead wife. Still later, she is revealed to be a Communist as well. Too much is going on.Campbell eventually gives himself up and in flashbacks, sits in a cell and talks to Adolph Eichmann.We even have a suicide at the very end. I think this might have been to take the audience out of its agony from viewing all this.The picture really had a lot of emotionally sick people in it. At times, Campbell was so viciously good at reciting his anti-Jewish denunciations, you'd really begin to wonder if he meant it.

enoughtoil

In order to enjoy Mother Night, I recommend that you have a lobotomy first. This has to be one of the most unpleasant and unbelievable movies ever concocted. More is required of the viewer than the usual suspension of disbelief: hence my recommendation of a lobotomy. But don't do it; you probably would not understand the movie afterwards, only now the reason would be having too low an IQ, whereas the previous reason was having one that was too high. To focus on just one of the many implausible, indeed absurd, features of the movie, the chief character, played by Nick Nolte, is a German-speaking American asked by the American government to pose as a Nazi in Nazi Germany; via his hate-filled radio speeches, he transmits surreptitious messages to the Allies that help us win the war. He is married to the daughter of a vicious Nazi policeman, who really believes in Der Fuehrer and Nazi ideology. We are given no reason to doubt that the daughter was successfully indoctrinated in the Nazi hatred of non-Aryans. So we have to wonder about this couple presented as being very much in love: what do they talk about? How does Nolte manage to love his Nazi wife?To focus on just one of the many unpleasant features of the movie, at the end Nolte is given the opportunity to prove to the world that he was indeed a double-agent. To say the least, he squanders this opportunity. I guess we are supposed to believe that he does so for a noble reason - to keep his spy activity a secret, so that prospective future American spies can engage in the same work - but to me this rationale doesn't make much sense and it is painful to watch the Nolte character accept it, if that indeed is what he does. You would think, after all he has been through, that he would want to educate the world as to just how painful the life of a spy is, so that prospective future spies would appreciate in advance what they were signing up for. Before signing up, these potential spies could apply moral pressure to the governments of the world that seek to recruit them: they could demand that these governments support them when the mission is complete, instead of abandoning and renouncing them.

Jonny_Numb

American playwright Howard W. Campbell, Jr. (played with a musty obsolescence by Nick Nolte) lives happily in Germany with his actress wife, Helga Noth (Sheryl Lee) before the beginning of World War II. At the peak of his life, Howard is drafted by an American agent (John Goodman) to become a spy on behalf of the Allies; forewarned of the risks the job holds, Howard has everything to lose, but finds the offer irresistible. Following the death of his wife and the end of the war, Campbell camouflages himself with the anonymity of a solitary life in New York City, which muddies his neuroses even further. The central question (indeed, a question that has frustrated many critics) of the movie and Kurt Vonnegut's source novel is, "is Campbell a hero or a traitor?" Director Keith Gordon and screenwriter Robert B. Weide offer us clues, but no answer, and this ambiguity–this NOT knowing–is what keeps "Mother Night" fresh and interesting throughout. At the beginning of the film, Nolte portrays Campbell as intelligent and confident; by the end, he's either scared and uncertain, or scared and COMPLETELY certain of his contribution/debt to humanity for the role he played in the war. Gordon applies a certain icy sheen to the images of the film's first half, which complement his portrait of the Nazi bourgeoisie and captures Vonnegut's dramatic side. On the flip side, when Campbell is confined to his lonely New York apartment (which he affectionately calls "purgatory") only to be discovered by a group of Nazis, the humor produced also is purely distinctive of the author, and provides a temporary respite from the dramatic tension that unfolds. The moral (even spiritual) paradox "Mother Night" presents doesn't lend itself to simple resolution, and to a degree, should be left ambiguous–the black-and-white scenes of Campbell staring wearily into space as he is imprisoned in Israel suggest an unspoken contemplation we are not made privy to–as Campbell is a character whose inner workings we wind up knowing very little about; the war changes him, coming back to America changes him, and meeting up with the Nazis in New York compels him to prolong the facade of his "act" even further, to the point where he can only stare wearily at an image of himself projected on a wall, spewing anti-Semitic bile. Perhaps that's the best reaction we could hope for.