kickboyface-1

I'm a fairly avid film guy -- especially when it comes to the avant garde and silent tributaries of cinema. (I mean, come on, I took film classes from Stan Brakhage for cryin' out loud.)Maybe I'm the stupidest kid on my block, but I'd never even HEARD of L'Humaine until it played at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival's "Day of Silents" last week at the Castro Theatre.It is absolutely stunning.You could get all snooty and long-winded about this film, but in my mind it all boils down to this: Metropolis meets Frankenstein in geometry class.I'd even go so far as to say this movie is better than Metropolis ... But I'm the first to admit that my thinking may have more to do with the fact that I've seen that film a couple dozen times (ie. I know what to expect when I see it) and I'd never seen this movie at all.When I first started this review, I gave it a 9 thinking nothing's perfect. But honestly, I can't think of something "wrong" with it. Viewing L'inhumaine for the first time was one of the most moving and significant viewings of film in my life. Right up there with 2001 in a Cinerama theater in 1968.Georgette Leblanc stands out well above an otherwise truly great cast showing a remarkable amount of breadth in her role. What starts out looking like a 2D character becomes someone much much bigger (with a surprising amount of subtlety considering the acting standards of both the French as well as silent film of the time).When I saw it, the movie was accompanied by the incredible Alloy Orchestra playing live (which kind of adds a very appropriate Devo overtone to it all). It's worth taking a look at their Website to see if/when they're playing with the film. If you've read this far in my review, it'd definitely be worth making a trip to see the whole spectacle. (I have very little doubt that they'll probably eventually release a version of the film with their soundtrack affixed. Get it if they do.)Thanks for reading.

chaos-rampant

The eye in motion, usually emblematic as a subjective shot from a speeding car; this has been at the center of this first great French tradition in film. Which is to say, a fleeting glimpse, the opening-up of the point of view from its fixed, static place in history and time to encompass a new, exciting view of life hitherto impossible; a mobility on the whole in all directions of perception, with finally the visibility of soul as the utmost aim.Two scenes here really take the breath away, both pertaining to the distinctions, and ultimately the inseparability, of reality and art, performance and life, external and internal image.The first takes place on the stage. The theater at Champs Elysee is packed full with an audience who have gathered to satisfy their morbid curiosity at the scandalous woman - a singer - who is about to appear; so everyone in the auditorium is at the grip of paroxysm not at the prospect of the anticipated performance, the stylized image, the evocative art, but the flesh and blood woman, the reality behind - again though a reality rumored from mouth to mouth, or read from the gossip column of a newspaper. So even before she has had the chance to sing, at the mere sight of her, the place is already in chaotic uproar - everyone wildly gesticulating, booing, others clapping and cheering on - already deeply affected, but unwittingly by another image - the immoral, scandalous woman - which they have projected upon her. And then she sings, and everyone pipes down.(a prelude to this image-within-an-image, or behind it, is the opening act of a dancing troupe; we see them dance, while on the backdrop behind them are painted figures of dancers, and when the curtain falls, it's again painted with dancers).The other powerful scene, involves the apparition of a young man thought to have died in a horrible car accident. Moments earlier we had been in the crypt with the dead body, a wind rustled the curtains, a gramophone played presumably eerie music. So, again a performance outwitting the performer, with reality - the kind of which you read from the obituaries in a newspaper, and hence the official, public reality - revealed by art as this unreliable facsimile of hearsay and conjecture.As with more famous American filmmakers - DW Griffith, Chaplin - it is this institutionalized, hypocritically objective 'humanity' that threatens to destroy the passionate, living individual who can barely make his own intentions known to himself; here it is the leader of some fund for the betterment of humanity who, having been turned away by the woman at a gala, scornfully turns against her.Purely in terms of images though, you will want to see a scene where - through the use of a 'scientific' device - we are quite literally transported on the lives of people by a singing voice. We steal upon them through a screen.This is how the filmmaker - who permits our vision to wander - was considered at the time then, as is also evident from theoretical writings of the time; a 'wizard' of science, as the intertitle informs us.And then the final reel. It is suddenly like Frankenstein's laboratory - full of mysterious futuristic machinery, whizzing with sparks of electricity - animated by bunraku play puppeteers. Figures dressed in black rushing everywhere, rapid-fire montage of faces, pistons, levers, jolts of energy, chaotic but coordinated movement in all directions. I've said it elsewhere about the advent of sound; cinema just wasn't going to be as adventurous, as audaciously freewheeling, freeform, freejazz and ahead of itself, for the next thirty years.Mostly everything takes place in some fanciful cubist sets, it's the first thing to note I guess, which you may want to see if you're interested in carpentry. But with such marvelous cinema on display, it's merely a footnote.

Igor1882

Goerge Antheil, in his autobiography "Bad Boy of Music," claims that the concert riot scene is actual footage of his own October 4, 1923 concert at the Théâtre Champs Elysées. This event helped seal his reputation as one of the leading modernists of the day. If this is true, then actual artistic history was made because of a reaction at least partially staged for the making of this movie. Among the luminaries present -- and possibly visible -- are Eric Satie (looking like a "beneficent elderly goat") and Darius Milhaud. A few days later, Antheil announced that he was looking for a motion-picture accompaniment to his Ballet Mécanique, a call answered by Fernand Leger.

david melville

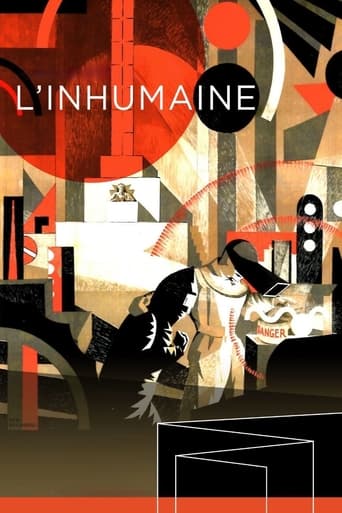

It is hard for film buffs today to see silent cinema as a modern art. What strikes us nowadays is the immense debt that DW Griffith owes to Victorian fiction, that FW Murnau owes to Romantic painting, that Fritz Lang (and this is true even in Metropolis) owes to ancient German myth. How strange and wonderful then, to see a silent film that owes no debt to anything or anybody, that sums up the notion of 'modernity' in a way no work of art had done before - and precious few have done ever since. Eighty years on from its catastrophic release, Marcel L'Herbier's 1924 masterpiece L'Inhumaine remains the first, perhaps the only, totally modern film.Most famous, of course, are the sets. A Cubist and Art Deco fantasy world designed by the artist Fernand Leger. Whether it's the salon of seductive chanteuse Claire Lescot (Georgette Leblanc) - a dining table afloat on an indoor pool, servants hidden by perpetually smiling masks -or the laboratory of visionary inventor Einar Norsen (Jacque Catelain) -vast and potentially lethal electronic gadgets, assistants in black leather fetish gear - we have entered a world where the past might never have existed, where the future can only be a continuation of now.Just as striking, though, is L'Inhumaine's 'emotional modernism'. While so much silent film acting makes us laugh at its melodramatic excess, Claire and her circle of admirers underplay their emotions as coolly as the high-fashion zombies in Last Year at Marienbad by Alain Resnais. (A fervent admirer of L'Herbier, Resnais has acknowledged the influence of L'Inhumaine on his own work, though he insists that "its ambition is more impressive than its achievement.") Leblanc and Catelain make a gorgeously impassive pair of lovers. Hieratic icons for an age whose one true god is the Image.David Melville