purrlgurrl

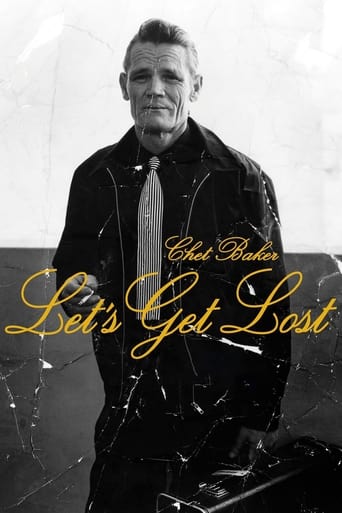

Beautifully filmed by a fashion photographer, Bruce Weber, nevertheless the ugliness of Chet Baker's life overtakes the beautiful images on screen. In Western culture, we equate physical beauty and/or exceptional talent with a depth of soul and substance that are often lacking if we look closely with cool objectivity at those we idolize for those traits. Great beauty or great talent aren't always bestowed on the good or the worthy, and Baker is evidence of that. He was a manipulative drug addict who likely would have wound up a petty criminal if he didn't incidentally have much more than a passing musical talent. It didn't hurt that when he was very young he also had the chiseled good looks of a movie star, looks later ravaged by decades of heroin use. Interviews with the women in his life reveal a strung out moocher who knew how to use their obsessions with him to support his drug habit, taking advantage of their romantic projections of a tortured soul onto a loser with some musical talent. One of them, jazz singer Ruth Young, states flatly that for Baker music was just a way to get drugs. In an interview with Baker at the end of the film, Weber asks about his current state of constant pain due to being cut off from drugs until he gets to Amsterdam. Baker refuses to rise to the bait and open up about the destruction addiction has wrought in his life. Ironically, Baker subsequently jumped, fell or was pushed to his death from his hotel window in Amsterdam. The film appears to have been meant as an homage to Baker, but instead reveals the ugly little drug addict he was. There is another myth in Western culture, the myth that in order to create the mind must be unfettered through use of drugs. After watching this, one can't help but wonder how much of Baker's creativity and talent were stunted rather than enhanced by heroin.

Michael Neumann

Fashion photographer Bruce Weber's lush, patchwork portrait of Jazz artist Chet Baker is more than just another show-biz biography of a self-destructive junkie. The romantic myth of Jazz itself is the true subject of the film, which unfolds in a fascinating, leapfrog structure at times even more elusive than Baker's own melancholy music. The musician himself is just out of reach, a vague outline of a man dimly revealed in candid interviews with friends, family, and other ardent admirers. Despite some often transparent idolization the film in no way whitewashes Baker's character, suggesting that he could be his own worst enemy, in particular around the many women in his life. Weber ignores the disparity between the singer's haunting good looks when young and the sad physical decline of his later years (his gentle, melodic voice would remain the same, even after losing all his teeth), choosing instead to capture some of the quiet energy of Jazz by allowing the music and imagery (beautifully photographed in black and white) to speak for themselves.

Robert J. Maxwell

Pretty sad stuff here. Chet Baker, a kid from Oklahoma, learned to play the trumpet and became famous in the early 1950s, partly because of his talent and partly because of his looks. He came to wide public notice as the complement to Gerry Mulligan's baritone saxophone in the piano-less quartet of 1952-1953. The sound was contrapuntal, uncanny, and unique. There had never been anything like it, and nothing since. But the two didn't get along that well, and Baker established his own groups and began doing the vocals as well in a voice about as good as yours or mine.By the end of the 50s Baker was on a downhill slide. A lot of his work, said to be fine, from the 1960s isn't readily available. Unfortunately what is available is Chet Baker crooning love songs and playing mood music at the slow tempos he seemed able to keep up with.By the time of this documentary, 1988, Baker no longer looked like James Dean. His face was that of a pinched, wrinkled, Oklahoma farmer out of a Walker Evans photograph from the Great Depression.I can't give director/photographer Bruce Weber credit for much in the way of generosity. There are too many stark, black-and-white closeups of that ruined face and stringy hair. The semi-stoned intonations of Baker's voice I attribute to increased age or current drunkenness. But the high-contrast photography is hard to forgive. Weber made his name in commercial photography. Most people probably remember his photos of half-nude young men. One of them, an ad for Calvin Klein, has a male model posed naked except for white briefs lighted in such a way that his genitalia were prominent. I don't find the picture offensive, only the motive behind it, which I take to be a desire to shock and to have one's name remembered. (Richard Avedon, a cynic if there ever was one, pulled the same trick with celebrity portraits that made the subjects seem ancient, debauched, or insane.) The same motive seems to lie behind the photography in this film, some arty shots of dogs prancing around in Santa Monica aside.Weber let's some of the people interviewed describe Baker's charm and his innate skills on the trumpet. Jack Sheldon, a trumpeter himself and one-time sidekick on a late-night talk show, is hilarious. Baker seemed to have second sight, says Sheldon. He didn't have to think about what note he was playing, he just put his fingers on the valves. "It was easy for him to know where he was. Not like me. I forget what bar I'm in. In fact -- where are we now?" We also get an assessment from one of Baker's embittered ex girl friends who puts him down scathingly, though she evidently had reason to. Nobody ever says, "Chet Baker -- what a nice guy he was." There's quite a lot of interview footage, as a matter of fact. Weber put a lot of effort into the film. And considerable footage from the 50s as well, including an appearance by Baker on TV with Steve Allen, a host and a fellow musician. Mostly, though, what we hear on the sound track is Baker mooning along slowly and feebly through love songs and mood pieces.See it, really, but be warned. It's gripping but it's painful too.

stuhh2001

We have to be grateful to Bruce Weber for giving us this film. Monetary gain could not have figured in on it, as jazz, in spite of the great artists it produces, could never attract the amount of people to make a venture like this profitable. The big bands of the thirties and forties had jazz musicians as members, and did incorporate some jazz solos in their arrangements, but could not be considered a jazz venue. They generated millions of dollars, because the dancing public was so vast, there was no TV, and the leaders were groomed to be lionised like movie stars. (See "The Trouble With Cinderella", Artie Shaw's autobiography on his disenchatment with stardom. Jazz was played in small clubs seating at the most two hundred people, while dance halls could accommodate as much as fifteen hundred dancers. Any footage of an important icon like Chet is welcome, but some scenes are not what they seem. The recording session is a staged event to simulate a record date. The opening scene on the beach sans Chet is gatutitous. Maybe Weber wanted to show the local Southern California beach scene that Chet loved. The scene in an amusement park with a stoned Chet on the "Dodgem" cars is puzzling. "Chet's women" add a great deal of interest to the film. His mother describes how the toddler Chet was transfixed by the sound of the big bands on the radio. Ruth Young daughter of a wealthy Hollywood producer, smitten with Chet and jazz, describes with an unusual lack of bitterness, the insane life of loving a junky, who was really in love with her inheritance and heroin, and made short shrift of her money to finance his drug taking. She sings briefly in the film and I thought showed great promise, but she failed to seek a career in music. Diane Vavra had no money for Chet to squander, but she filled in as someone knowledgable about music to help Chet. Carol Baker, "the long suffering wife" (and how she suffered) gave Chet three beautiful children, who Chet barely noticed, or provided for in his chaotic race to the grave. With all that said, what about the music? Well I can tell you that in an era of great heroic trumpet superstars, like Dizzy Gillespie, Roy Eldridge, Maynard Ferguson, and many others, who could dazzle you with notes in the highest register of the trumpet, and improvise incredible melodies in the upper register, and "scream" above a roaring fifteen piece band, Chet was not in that mode at all. He rarely practiced, had no high register, but wove a soft filagree of delightful improvisations on standard popular songs. In my opinion he reinvented trumpet playing in the fifties. His playing said, "Dizzy's great, but I do it this way." His movie star looks did not hurt his appeal one bit, and his singing which has many detracters, I think will prove to be more appreciated in years to come. I loved every note he played and sang when I first heard him in the fifties, and my appreciation and love for this man, grows every year.