chaos-rampant

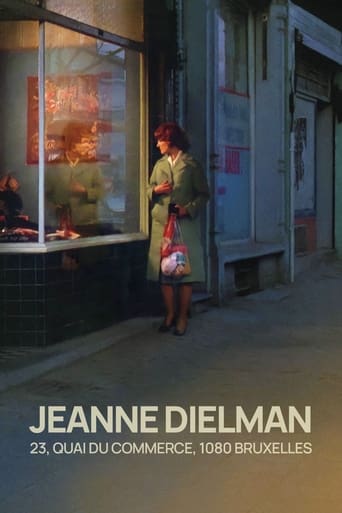

We are torn in life by emotions, desires, grievances, thoughts that surge through us and back to create self. We suffer from the pull of events outside of us; but we also suffer more acutely it seems from a life that has no pull anymore, from being every day in the same room without air.This is the essence of modern film for me, indeed what sets modern man apart, it's the baring of this self who, having sated apparent needs, finds himself no closer to fulfillment, the walls closing in, the air being sucked out from life. Neorealist characters could at least point around them to a life of squalor and ruin as explanation. But Antonioni's characters?So I'm after filmmakers who abet stillness and the wisdom that comes from it, looking for a cinema of awareness (never aesthetics). Because most movies can splash a bit of passion and noise about our predicaments. But how to achieve cessation? How to inhabit the world and our self in a way that we come finally to a measure of realization about process?Here is one of the simplest suggestions to the question, all about creating emptiness. It's my first acquaintance with this filmmaker and I'm bowled over that she made this at 24. She must have been a brilliant mind, a woman worth knowing.A woman simply goes about her daily life. She's a lonely widowed housewife, doing chores, preparing food, washing the dishes. She's also a prostitute, Akerman makes a point to reveal this at the very beginning. Her son comes back in the afternoon, she prepares dinner. She has to wake up again at dawn to make breakfast and see him off.We have no plot, no drama, and only the interminable life in between. Small rituals like trying to get her coffee right because she has nothing else to do. There's only her son in her life. Talk between them is little and the boy's habit to not pay her much mind exists on a razor-sharp edge between neglect and ease. It's heartbreaking to see how she spends her whole day tending to menial chores and he just comes in and sits to eat with barely a word. Mothers will able to relate.But this is the whole thing, how we register these moments. It's sparse, simple, minimal pundits say; better yet, it's like a modernist mantra where by repetition we come to acuity and focus about the fabric of emptiness from which sound comes. In our case, life itself, yours and mine.Is it a horrible ordeal? Can we bear it nonetheless, even if less than ideal and not what was hoped for? Is there an exit?Akerman and the regal-looking Seyrig have conspired between them; Delphine will move gracefully and with complete purpose, the film is a series of tasks carried out without complaint or hesitation, Chantal will film simply the room, allowing us emptiness to receive it. It has some of the most exhilarating atmosphere of any film I've seen.Then a pot of overcooked potatoes or a piece of cutlery that slips from her hand can ring far and wide with the vexation building up inside. When she tries to make the same small-talk she finds inane. When she picks up the baby, unsure if even out of affection anymore.The whole film is inverse Cassavetes, including the snuffing of courage at the end (he never does it). Oh it's a great ending that will brand your insides. But she had already done this for me and to leave her crushed like this, are we now more awakened or less?

evening1

A compelling portrait of emotional alienation that is reminiscent of Polanski's "Repulsion." Jeanne (Delphine Seyrig) seems a domestic goddess -- carefully planning each well-balanced meal, doting on her only child, and keeping a pin-neat apartment. But she's robotic with people -- seemingly just tolerating their invitations and chatter and never saying much more to her son than "Did you wash your hands?" before breakfast.Despite appearances, the perfectly put-together widow ekes out a living by turning tricks each afternoon in her bedroom, and then scrupulously scrubbing herself after each encounter. With each successive john, we see a little more of how Jeanne feels about her hidden occupation, till after a third encounter we are left with no illusions at all.Does Sylvain suspect how his mother earns a franc? As the 3.5-hour film inches along, seemingly in real time, one's theory on this question may evolve.In all, this film drives home the psychological truth that the more perfect a person may look, the more disorder she may be hiding below the surface.This is a devastating portrait of the high cost of keeping up appearances.(I was saddened to read on Wikipedia that Mlle. Seyrig, who played the opalesque heroine, died some 15 years after the film came out, of lung disease. This was one bravura performance.)

homerjethro

Really, really wanted a slice of meatloaf while watching this. Just a few observations from someone with a huge Criterion library who enjoys "artsy" films:(1) This film might have appeal to students who want to see the results of static scenes. Or it might impress those who need to actually see boring routines play out to get the point (the pocketbook on the table gets my vote for best actor). Or it might be an opportunity for people to yell advice at the screen ("Sit down while polishing shoes!" "You're kneading the meatloaf wrong!" "Turn on the radio while you're working!"). Otherwise...meh.(2) For those who insist that the length is appropriate, I haven't noticed anyone saying that the film would be better at six hours. If she really wanted to make a point, why not film six days? Heck, who knows what exciting things she does the rest of the week...perhaps Ackerman just chose the three days when little happens other than routine (seemingly embraced by the protagonist with little effort to perk up her existence. Maybe she's enjoying herself, or maybe she has an active imagination that allows her to entertain herself).(3) Drying paint on walls has no choice in its banal existence. Humans do have choices. Anyone who doesn't understand that or doesn't know people who don't exercise their choices & live in ruts needs to volunteer to work with the public. Then Ackerman's film won't seem so much like a "masterpiece."(4) If this film is "brave" (whatever that is supposed to mean), here's an exercise in artistic courage: Take a blank sheet of paper to your local art gallery and insist that they display it (perhaps with a huge price tag) to demonstrate your minimalist talent. If they are the pretentious sort and comply, you'll be sure to be lauded by the same sort of snobbish viewers who love to chide others for calling out pretension.

hotel-419-417395

This movie is deliberately different, all in the service of telling us something we didn't know.Movies are about movies. The borrow plot, character, lighting, sound editing and camera angles from what went before. Since "Birth of a Nation" introduced close-ups, cross cutting and cutaways in 1915 everyone has adopted that vocabulary for story telling. This movie throws all that out: The camera is fixed and stares at a scene for a very long time. Scenes had to be performed all the way through when they were filmed, because each was done in a single shot.Movies use telescoping of time to compress the happenings of a long period into two hours. This movie tries to avoid that, depicting mundane tasks in their entirety. We watch Jeanne Dielman prepare a meatloaf, step by step, wash the dishes (her back is to us!), smooth the bed, or go shopping.Movie use facial expressions to express feelings. Spoiler alert: When we get strong facial expressions from Jeanne Dielman there is a very good reason. And that only happens once in a three-hour, 21 minute film.Movies use broad strokes to carry the audience along. Spiderman supplements explosions with 3D to keep me occupied. By contrast, this film uses subtle changes. You must watch closely to see what happens.Most movies come to you. This movie requires you go to it. If there is dullness it is among those viewers who think that because they don't get something it's not there to get. There is plenty here but instead of being served to you it has to be harvested. And it is very fresh.