Zoomorph

Long, slow, static shots. A girl does a couple random, pointless, inane things in a small room. Long fades to black. Bland narration. Nothing very interesting happening. It actually starts to get slightly interesting when we finally get a second character who provides some real talk. Then jumps into an incredibly long, exaggerated, and boring lesbian scene. The end.This is just another artsy fartsy film that is fairly pointless and meaningless and vapid. It's some kind of "reflection" on sexuality, but with nothing insightful or even interesting to provide the viewer. The photography is just average. It slightly reminded me of the vastly superior film "Un homme qui dort" from the same year.

Hitchcoc

Having been interested in avant-garde cinema for about 50 years, I could see myself with my friends back in college, parsing something like this. This was the time of an eight hour film of a man sleeping. Every hour or so he would turn over or readjust his pillow. I suppose this lays a foundation for a filmmaker to eventually break from this into something with some sense. This film about a girl who spends a week eating powdered sugar, painting her apartment, and moving her mattress around probably does something for someone. She also poses in the nude, inviting voyeurism, which, I suppose we can only guess at. The other two thirds of the film, a meeting with a blue collar worker to watch a gangster movie, and a lesbian love scene, hang on for what seems like hours. Anyway, I haven't anything to contribute other than the final love scene reminded me of a film about insects, where a wasp struggles with an insect of equal size, grasps him and stings him until he is dead. There is endless convulsing, short moments of relaxation and exhaustion, and, finally, the coup de grace.

Gloede_The_Saint

Not quite sure what this is supposed to be or mean. Don't get me wrong. I'm not one of those who strive after meaning, allegories and new dimensions or need such things to get involved in a great film. Sadly Je, tu, il, elle did not strike me as a great film.As a fan of long static shots I might not have had as big trouble as some others seems to have had. But the beauty of the imagery was minimal. And the lesbian love scene in contrast less grey felt not only dead but entirely inhuman and distant.The 30 minute opening act was though it's many attempt of humor more or less dull. Her inner dialog struck me as somewhat silly rather than funny, interesting and deep. My interest grew during the second act, which is more dialog driven than the first and the last.If anything this is a revolt against form. And I can in some sense appreciate it for this. Anything new or different will obviously create some interest and start some sparks. But Akerman did not manage to bring me in with this one.

madsagittarian

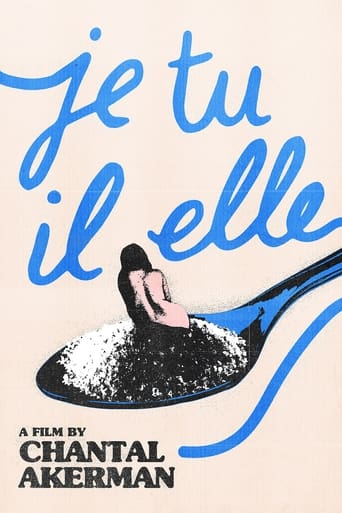

(spoilers abound, if such a thing is applicable for such a bare-bones narrative...)Chantal Akerman's first feature is also her first work to play with narrative structure (I do not include her early short, SAUTE MA VILLE, because it is loose and spontaneous). This film has three spare sequences. The first features Akerman ("je") in an empty apartment, spending days writing and re-writing a letter (which is read in the voiceover- "tu" us, the audience). The narration is diary-like, chronicling the number of days and monotonous routines that occur even in this minimal environment (writing, moving around a mattress, her sugar diet). Representative dialogue: "I wrote six pages to say the same thing."Suddenly, the scene shift to an extreme long shot of Akerman at the side of the highway during a hazy overcast. This begins the second movement, as a trucker ("il") picks her up. He is a ruddy, blue-collar man who drinks beer in one big gulp (she in little sips). There is no onscreen dialogue until he gives her instructions on how to masturbate him. After that, there is one long take where the driver talks about his wife and kids. The "il" sequence ends on an ambiguous scene with him shaving in the bathroom. Suddenly, this driver appears to be rather dashing! (on the way home to his family perhaps?)The final third begins with Akerman buzzing an apartment ("It's me"). A woman ("elle") answers the door. "I don't want you to stay," she says. They embrace. "I'm hungry", Akerman replies. Then there is a long take of her eating, and a much longer take of the two women making love. In the morning, Akerman gets up to leave. The end.In this remarkable debut feature, there are several indications of Chantal Akerman's signature. Most tellingly, the film shows her use of long single takes, in real time. Most viewers would be apprehensive about this, but actually this style is highly addicting. The use of the single take may seem rather improvisational ("Let's keep the frame wide, and see what the characters do."), but I believe this film was much more meticulously planned. Akerman's long takes force the viewers to study the relationships on the screen. The more one stares at these unbroken compositions, the more one understands their properties, and their relation to the central character. In the long scene in a restaurant (where she and the trucker are in a booth watching TV), or in the bar (where he is among some acquaintances), she seems to be pushed right to the edge of the frame. During unbroken sequences in the truck (particularly when she "stimulates" the driver), she is entirely offscreen. Once one realizes what happens (or does not happen, for that matter) in the "plot", this artistic choice begins to make sense. It is evident she is not comfortable in this situation. We realize this sequence is just a ploy for her to get to her lover. When she nonchalantly masturbates the trucker, the screen is also devoid of passion because she is offscreen.Another Akerman-esque property is when scenes are separated with overlong stretches of black leader. This is not a budget-conscious device, but a way of putting the temporal logic of the film at bay. With sequences being broken up, or for that matter, being highlighted by their black brackets, we are uncertain of the time that passes from one to another-- we are purposely frustrated in understanding their connection to each other. Again, with her ambiguity, she is forcing the viewer to analyze the characters (not too many filmmakers explicitly trust the audience this much, to know they can figure it out themselves instead of being spoon-fed everything).It has been said that Akerman wanted to be a filmmaker once she saw Godard's PIERROT LE FEU. Perhaps what she most learned from Godard is what he refers to as "the moments between the plot". In Godard, the plot is forgotten- it merely becomes a springboard for him to run with his ideas. In Akerman, the story is often quickly explained away in voiceover, so then she can spend the duration of the film studying the implicit characterizations.A trend in her characters is that they tend to operate on the basest of instincts- the spare dialogue mostly correlates to their hierarchy of needs: "I'm hungry, "I'm cold". (is it any wonder that she also made a film titled just that?) Akerman has adapted a near-Bressonian minimalist use of dialogue. The speech is condensed to the marrow- telling one very little, but everything.