hughman55

This documentary is about victims and perpetrators. The victims are Helen, a Holocaust survivor, and Monika the daughter of, Amon Goeth, the camp commandant where Helen was held as a prisoner/slave. Monika never knew her father, Amon Goeth, and she has sought out a meeting with one of his victims for a closure that is not possible. Monika knows about her fathers atrocities from films, documentaries, word of mouth, and from her mother. Helen knows about his atrocities first hand because she lived them. Monika freely admits that she has hated her mother, Goeth's mistress at the concentration camp, since she was eleven. She is adrift in life. Her father was hung for war crimes when she was an infant but her problems in life go so much farther than the memory of, no knowledge (she never even knew him), of a man she never even met. Her mother Ruth was, well, she loved and lived along side a mass murderer. Draw your own conclusions about that. Monika has. Monika has reached out for a meeting with one of her father's surviving victims for some unattainable catharsis. Helen, the survivor of unspeakable cruelty at the hands of Goeth, surprisingly, agrees to meet with her at the site of concentration camp in Poland. The two women's reasons for going to Poland and meet could not be more divergent. If you were in a car and another person were in another car, and the two of you were hit head on by a third car, and the driver of the third car turned out to be your father whom you'd never met, would you turn to the other accident victim and ask for help? That's what essentially happened here. Monika came to Poland to meet Helen and receive forgiveness, absolution, sympathy, something. But there is nothing in this world that exists that Helen can offer her. Despite that, Helen does share with Monika that her mother once said to her, "If I could help you, I would. But I can't". It is generous beyond measure because she is saying this about a woman who lived with a man who shot concentration camp prisoners from the balcony of their villa for fun. Who knows what tone came with that feeble comfort. But Helen understands that although Monika never even met him, she too is one of Goeth's victims. Even after all that she's been through she tries to give Monika some peace in her anguish. Almost as disturbing as seeing Helen recount and relive the atrocities she endured, was reading one of the reviews here that says, "As several viewers have noted, Monika comes across as the more sympathetic of the two women. Helen was severely hurt by her childhood experiences, and has never fully recovered. She still views the world as hostile, even when it is not. Monika is not an enemy. One would have liked to have seen Helen express the forgiveness for which Monika so obviously hungers." First, no one noted that Monika was more sympathetic so that's a strange way to begin an observation. Second, "fully recovered"? Who recovers, fully or otherwise, from surviving being a prisoner in a German concentration camp? Seriously. And forgive Monika for what? There is no connection. Then there are some strange assertions that Helen has not moved on and forgiven. Helen is the one who suffered through the Holocaust. Her husband did too. Her husband survived the Holocaust, but couldn't survive the "surviving" and took his own life at the age of sixty-five. When exactly is one supposed to get over all of that, move on, and "forgive"? What an inexplicable comment to make. Monika is most definitely a victim of the Holocaust. But not in the same way as Helen. It is one thing to be tangentially connected to it, and another to have experienced it's atrocities first hand. Monika, desires, and deserves sympathy. Helen has no ill will whatsoever towards Monika, who is innocent of the crimes of her father. But Monika has to find her own peace. It is not Helen's give her. Astonishingly, at one point when they are going through the villa together; the place where Helen was kept as a prisoner, beaten, pushed down stairs, the place where Helen watched Goeth shoot prisoners from his balcony for fun, the place where she watched his dogs tear prisoners to shreds for amusement, Monika attempts to explain away some of the killing, to Helen, as "disease control". It is jaw dropping to watch. If it wasn't clear before then, the viewer knows at that point that this meeting should never have taken place. There is no resolution to this other than to survive. One of these women is doing that. The other is trying.

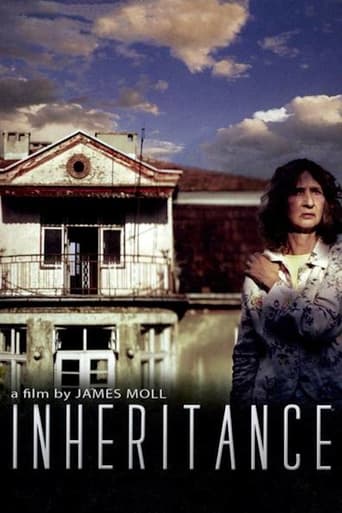

Martin Teller

An odd coincidence that I watched this after I Am Twenty, another film about people whose fathers were lost in WWII. But Monika Hertwig had a very distinctive father: Amon Goeth, the vicious Nazi concentration camp commandant immortalized in Schindler's List. Monika struggles to cope with the atrocities committed by Goeth, and reaches out to Helen Jonas... a survivor who, as a young girl, was taken into the Goeth villa as a household servant and suffered abuse directly from Goeth's hand. The meeting between these two women provides moments far more shattering and resonant than anything in Spielberg's film, especially when they return to the villa. A very moving story of women trying to find peace with their histories, even better than Moll's previous Holocaust documentary, The Last Days.

stephanlinsenhoff

A 1956 hot summer day opened the mistrusting relation between daughter Monika and her mother Ruth Kalder (her fathers mistress at Plaszóv) for a short moment the door of German denial.The trusted grandmother Agnes Kalder: "Monika, they hanged him. He killed the Jews." 1993 screen saw Monika Hertwig two dimensional Ralph Fiennes in Schindler's List: the SS commandant of the concentration camp Plaszóv, Amon Leopold Göth, her father. For the daughter it was a brutal mirror event: looking at the actor, seeing her father. Not only Germany's general German shame but her own, personal shame as German. The one possible way: en face as I myself. Next: the letter to her fathers schindlerrescued slave Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig and their visit at Plaszóv. Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig in an interview: "She wants to be my friend, but it's too difficult for me." A crime of guilt is court sentenced (it happened with her father). Then: the boy Bruno in The Boy in the Stripped Pyjama: "What have you done?", Shmuel answers: "I'm a Jew". How is it possible for a country's and a child's shame that can be handled of "an artist of evil - grandly deranged, creatively sadistic. He would set his dogs on children and watch them be devoured. The people he whipped, had to keep count of the strokes. If they lost count, the whipping started from the beginning". The solution for the night porter Aldorfer in Il Portiere di Notte: "I have a reason for working at night. It's the light. I have a sense of shame in the light." It seems that the light disturbs Monika: she hides "behind a mop of hair that often hides her eyes." But why looks the guilty Jew Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig directly at the camera, still grieving. A possible answer can be that she realized as Göth's "stupid Jew that I had to grow up. I'm no more child, I'm no more with my mother, I'm here and I have to obey." R Rorty, 1989, sees the fundamental dimension of a human being is the ability to suffer, to experience pain and humiliation. It is this Helen did and: did not loose her dignity.This precious piece of humanity the brown years took from the different-guilty and the having-seen-looking-away-shame. Helen Jonas-Rosenzweigs first husbands last words: "I'm haunted every day, I can't go on." As many others: one of them Primo Lev was told by the guards: you will never leave the camp and if, you leave behind dignity. "That was what the German did to us", says Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig. Hanna Arendt tells of the Jew Jesus and 'scandalon', actions that can not be judged or forgiven. The Readers Ilana Mathers: "People ask all the time what I have learned in the camps. They where not therapy. Do you believe it was a university? We where not there to learn something. What do you want? Forgiveness for her. To feel better yourself? Go to theater if you want catharsis, go to literature, don't go to the camps. Nothing comes out from the camp. Nothing". Evil by an evil person in an evil environment has a small other side: those who resist/ed. It is a persons choice beyond either cholera or pestilence. Helen: "… I'm no more child, I'm no more with my mother..." Helen confronted the evil 'en face' (not the evil devil her) with the suffering, the pain, humiliation. Not loosing dignity. In the villa Helens words for Monika: stop repeating from now on what others say: "start something different." Helen is for the arguering child Monika the seeing and not looking away 'stand-in-mother': "… She's a victim too. She's scared, lost, and feels guilty." Instead of the good parents they where not the good-enough-father but the 'evil-enough-father', not the brave-enough-mother but the shame-enough-mother. Is Monika prepared after Inheritance to face 'en face' the pain of shame, the suffering shame and the humiliation of shame: receiving dignity and: "where I am able to live with the truth". The Readers Rohl will be wrong: " ... If people like you don't learn from what happened to people like me, then what the hell is the point of anything?" When seeing the inside of the farm, Bruno remembers that supper waits with roast biff. Too late: "It's a shower". Both holding tightly hands.

Danusha_Goska Save Send Delete

Monika Hertwig is the reason to see "Inheritance." She comes across as a very real, lovely woman, someone you'd like to have as a friend or next door neighbor. She's a grandmother and housewife, in her sixties, very tall and slim. She's sensitive and caring. She's also the daughter of Amon Goeth, the commandant of Plaszow, the Nazi concentration camp depicted in "Schindler's List." In that film, Ralph Fiennes played Monika's father. Monika was born in 1945. Goeth was executed in 1946.Monika reports how she learned, slowly but surely, as a child, who her father was and what he did. Monika contacted Helen Jonas, who, as a child, had been one of two Jewish woman named Helen who had served as Goeth's slaves in his Plaszow home. Jonas lived in New Jersey. Monika and Helen met at the site of the Plaszow concentration camp, and James Moll filmed their meeting.As several viewers have noted, Monika comes across as the more sympathetic of the two women. Monika allows her emotions to show. She weeps profusely when meeting Helen and appears to be approaching Helen for a hug. Helen rebuffs her. It is clear that Helen was severely hurt by her childhood experiences, and has never fully recovered. She still views the world as hostile, even when it is not. Monika is not an enemy. It is her profound misfortune to be the biological child of a very evil man, but she herself is not evil. One would have liked to have seen Helen express the forgiveness for which Monika so obviously hungers.Monika never knew her father, and comes to know him from others' accounts, including Spielberg's and Fiennes' depiction of Goeth in "Schindler's List." Helen fleshes out the depiction. Goeth pushed Helen, a mere child, down the stairs in his home several times. He knew that Helen, his little slave, had a boyfriend, Adam. One day Goeth teasingly asked Helen where Adam was, and, then, within minutes, shot Adam. Goeth kept two large dogs at Plaszow. He trained them to maul and kill human victims. He robbed Jews before killing them. Monika has a cigarette case from her father. She suspected that he stole it from one of his Jewish victims.Most mysterious is Monika's mother, Ruth Kalder. No one in the documentary mentions it, but, weirdly, Ruth looks Jewish; certainly her features are those that Nazis would identify as Jewish. She had abundant, striking black hair and a prominent nose, which Monika inherited. In one photo, Ruth looks very much like Chico Marx. This is not a wisecrack, but a statement of fact. It's more than a little odd that Goeth would select a girl who looked so Jewish, even as he sent thousands of Jews to their deaths for their allegedly obvious "racial inferiority," a racial inferiority that was supposed to be obvious in their dark Semitic features, allegedly so different from blond Aryan superiority. One has to ask, why did Ruth love Goeth? The documentary does not probe this pressing question."Inheritance" includes archival film footage of the actual execution, by hanging, of Amon Goeth. It was a grotesque event. Hangmen need to know their physics. Length of rope and drop must be calculated to produce a clean death. The masked executioners in Poland tried to kill Goeth two times before getting it right on the third try. The viewer may question why it is important to view this spectacle of death.I would like to have seen some harder questions asked of each character. Monika: Point blank, did you inherit any of your father's evil? Where did that evil come from? Where did it go? Is he in hell? Can God ever forgive men like Amon Goeth? What would you do if you were God? Would you send your father to hell forever? If not, why not? Helen: Will you ever be able to forgive? Will you ever be able to move on? Will you always be stuck in victim mode? Why are you so harsh with Monika? What about Helen's children? I would have liked to have heard more about their experience of being children of survivors. I would have liked to have seen some depth given to Poland. The bulk of this film was shot in Poland. There were Germans and Jews but there were Polish victims and heroes and perpetrators as well. Poland isn't even background in this doc and that is a failing. Two suicides and one drug addiction are mentioned, but not explored. In short, I was very moved by this documentary, but I would like to have seen it go deeper into the very big questions it touches on.