tfmorris

One thing is for sure. When Edgar is walking along the train tracks, he pretends to be too involved with what he is reading (a blank book) to acknowledge the train's greeting. But he is involved with the outside world. Even though his face is in the book he carefully steps over the obstacle in his path. He is a poser.The girl's situation begins to make sense to her only when she considers her history. American media does not give us a history. That's why Godard sometimes talks about "She Wore A Yellow Ribbon", a movie in which the John Wayne character is so concerned about the Indians. So, of course, things are not going to make sense to us. We are going to see things as they are presented to us. Cool cars and hot chicks! But the naked girl in Friedman's "Steambath" says "I did well, didn't I." While we're thinking she's great (as a sex object), she's looking to be related to as a human being.Edgar wants to be an adult. He wants to see himself in connection with his childhood and old age. He doesn't want to be someone who lives as though they would never die--and thus go with the way things are presented to him. He gets on the train of the city with "future" in its name, but then steps out. Who can imagine a future in such a place? And then she tells him: The man comes home and tells his little girl that he did good work that day. He could have had it. She takes off her jacket and whispers to him, and he stays objective. No, no, it is perfectly fine for me to stand out here on the outside of the window looking in--no problem. This is why the film ends in a train station: it is where he didn't get on.And what a girl! The reason why she is poor now is that she refused to read the American-type lines in the soap opera she was performing in: a truly virtuous person. In "Forever Mozart" the captives nod to each other before he takes issue with their captor's mistaken remark about Danton and the Directory. They know they are going to be in for a hard time, but they don't think of what they shall eat or what they shall drink; they just pursue righteousness.On the old man in the shower. The young man holds her hand. She is not relating to him as an old man who can hardly walk down the steps, she is relating to him in continuity with the very agile young man that he once was. The young man is present.If you don't relate to the present or to the future what do you have? It's like a poor man's dream, I'm going to get material stuff, and then more material stuff. We go from flower to flower thinking that summer will never end. What a joke, being proud of how much your car costs in a world in which 4 million children a year die from the effects of malnutrition. History has been replace by technology. We are conditioned to look for the boobs, or whatever by TV. It trains our eyes. That's why Godard characters walk along the side of the road. They don't want to be separated from reality by technology. Contrast the World War II boat going over the waves with the helicopter. The sports car just zooms off. It's occupants merely relate to its interior, not to the world about them. Relating to the world around one would mean respecting people's humanity. Rather than needing a pep talk to be tough with them (hand hitting palm), they would not be cheating them with a tricky contract. Indeed, isn't that what the hand hitting the palm means: be tough; don't start relating to them as fellow human beings. Edgar stops visiting the old art dealer as well. The pen drawing up ink represents how the old man draws life from Edgar. But after Edgar stops coming by whatever ink is there is dried up.The sunlight reveals the Vietnamese maid's body through her dress as she looks into the distance, just as you can see the black bra of the girl was in love with as she looks into the distance. But the old man just relates to her as a servant. An old man couldn't very well love the maid. Though he could arrange for another old man to have a prostitute. The maid says that the Americans are everywhere. "Who remembers the Vietnamese resistance?" She has got the same insight as Edgar. He could draw life from her as well. He's like Edgar this way. Just do what is expected. Give the girl a tip. Hell, he doesn't even say anything to her. She's just a maid. He doesn't even give her an acknowledgment of what her people went through. He does better than Edgar though. At least he commits to Edgar, even though he is counseled against it. He is responding to his own need. When the film asks whether humanity will survive, it is talking about non-Americanized humanity. It seems to be implied that humanity will survive if it deserves to survive. If we strive for real life we will receive. But hey, I'm tired now. I wonder what's on TV?

MisterWhiplash

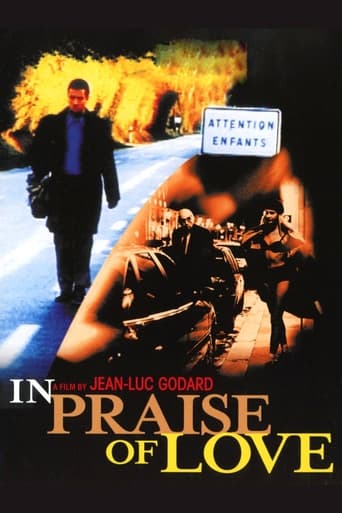

I heard many good things about In Praise of Love- and a few very bad things- so I proceeded with the same caution with most of director Jean-Luc Godard's later films. I thought that, at best, it could call as the grand 21st century precursor to Notre Musique, his latest film, which is one of his best in many years. But watching In Praise of Love is, in some ways, even more frustrating than his bad films because it's one of his better films as a director of scenery and compositions, of attaining that "Paris" mood with his lens. He also has some points here and there that are worth listening too. Unfortunately, a lot of them are also full of hot air, and practically border on being the senile rantings of a man past his prime- ironically a film that is meant to be all about memory, what it means to remember one's country, one's personal history, one's culture, and, if luck should have it, one's possible love. There's also an underlying bitterness to the proceedings too, and even when I heard and saw the sparks of poetry that made me remember seeing the films of his prime in the 1960s, there's also a good deal here that had me raising eyebrows.Maybe that was bound to be my reaction to it, anyway. After all, I'm not just another person walking this Earth, I'm a stupid American without a history who watched Hollywood movies that are, in reality, controlled by the government. At least, that's what Godard would say. And, as well, that because we're the United States of America, we don't really have a country anyway, unlike Mexico or Brazil or whatever. Why doesn't he just use his mouth-piece actors and call me "fatty fatty fat-fat" and get it over with? Ironically as well, this is a filmmaker who once said "there's no use having sharp images when you have fuzzy ideas." Well, a good deal of the ideas are fuzzy here. Though on the reverse side there are a few that are pretty sharp. Like when the character Edgar, the main link in the story who's in part one (the black and white filmed section) an auditioning filmmaker for his project and in part two (digital) doing research two years before, talks to a woman about thinking of something, but thinking of something else. It's much simpler an idea than a lot of the other semantics Godard floats around, and it's actually a good little speech. I also thought the old men (wait, is 'old' right according to Godard, or child, can't say) discussing their own pasts, and what it means for them, or what it doesn't mean. That it's still there for them, their own horrors and occasional joys, are enough.But what becomes all the more frustrating are the ideas that don't hold any water, or seem a little patched together from scraps of notes from Godard's ramblings out on the streets of Paris and, of course, by his long-loved beach scenery. What am I to make of the whole concept of there being no adults, or there being adults? Or the blank pages in the books (nothingness I guess, that memory of what's written is no more, I had no idea really). Or the not-too-subtle attacks on Spielberg? How do we know what Godard is saying to is really true anyway, because of the veneer and sometimes appeal of the documentary form? And what confounds me more is how at times, when the usual tactic of Godard's to do the overlapping conversations- this time in different languages in spurts- didn't bother me as much, as I found that to be an interesting way for Edgar to go about hearing things and experiencing people's words and memories for his 'project'. Unlike past Godard entries, particularly King Lear and Nouvelle Vague (1990), the poetry, if it is as such, in Godard's essay-form of film-making holds some water here, and there are a few passages that come along that are striking, that do connect with the splendid street photography and other set-ups.Nevertheless, it's still hard for me to recommend the picture, unless you're already a Godard fan and will check it out either way of what I say, because of the sense deep down of a cranky deconstructivism in Godard's messages, and unlike his best satires and experimental work doesn't have the balls to call on both sides (Week End had that best). So, France has a "real" memory and American doesn't? Why, because Shakespeare wrote half his plays there? I'm not against people who want to put some criticism to Americans *thoughtfully*, but when done in such a blunt, repetitive tactic, it becomes less like philosophy and socio-political discourse than it becomes more like name-calling and shallow, chronic dissatisfaction with any system outside of his own, albeit with some reservations there too. In Praise of Love is not one of Godard's worst, but it stops and goes in how it really connects, and at the end I wondered- aside from getting the shots of Paris and the countryside with his great DP, and the small bits of inspiration- why the hell Godard is still even making films anyway.

christophaskell

Jean-Luc Godard is amazing, still. The ways in which he breaks the accepted norms of cinema are brilliant. With 'In Praise of Love' Godard combines a quietly satirical screenplay, a score reminiscent or Kieslowski's 'Blue', and beautiful cinematography to paint his vision across the screen. I'm not going to begin to try and dissect the dialogue, as there's so much happening visually and aurally in one shot of this movie, that in only one viewing I simply could not grasp it all. This man deserves so much more credit and respect than he gets. He is still revolutionary, and boundary-pushing, and films like this show why. Rating: 34/40

lizgrass

Jean-Luc Godard is a cinematic genius, there is no denying that. He was a major player in one of the most influential movements in the history of film, the French New Wave. His films Breathless, Contempt and Masculin-Féminin are among the greatest ever made. He is a legend to movie-goers and filmmakers alike.That said, this movie is a dud. In Praise of Love (Éloge de l'Amour) is confusing rather than enigmatic, and boring rather than thoughtful.I wanted to like this movie, I really did. I wanted to act intelligent and proclaim, `Ce film est excellent!' Mais, I mean, but, it isn't. Watching In Praise of Love is like reading a graduate philosophy textbook that is written in French poetry, with translation in hyroglyphics.The story, if one can call it that, centers on Edgar, a man confused about his own emotions, who is trying to make a film (or novel, or opera) about relationships. In a flashback that comprises nearly the entire second half of the movie, we come to find out that one of the women Edgar was hoping to cast is in fact a woman he met years earlier when speaking to a couple persecuted during World War II who are in the process of selling their story to Steven Speilberg. (Don't worry, I've seen the movie, and I'm not quite sure myself.)Several mentions are made of `stupid Americans', and this movie made me feel like the stupidest of all. But Godard is Godard, so rest assured, his strange vignettes are just as haunting and aesthetically beautiful as they are perplexing.