Condemned-Soul

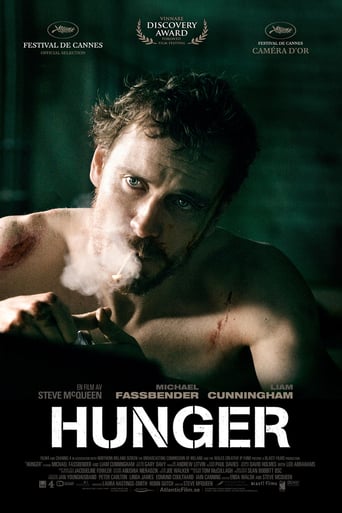

'Hunger' is a British-Irish Historical Drama about the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike. It's a film that's tough to watch, showing prison brutality and conditions at its most absolute rawest, and it visually looks the part (age and grime and all). Being fact-based certainly lends emotions to events depicted which would be absent if it were a fictional account, but the direction here is forgettable. Too many meandering scenes of banal activities waste precious time in a picture that wouldn't make it past the hour mark had liberties not been taken on scene lengths where the camera lingers on something uninteresting for too long. We even get a man sweeping liquid down a corridor for a couple of minutes, when you get the point after 10 seconds. It serves little purpose, and the static camera-work is detriment to the cause. Steve McQueen would repeat this dull filmmaking style with 12 Years a Slave many years later. One impressive scene is when Michael Fassbender and Liam Cunningham share time together, giving us a 17 minute unbroken shot of a conversation. But that's not down to direction or cinematography, but to the credit of the actors for memorising their lines. Speaking of Fassbender, he undergoes a shocking physical transformation (clue is in the title), displaying his commitment to accurately portray and tell the story of the character. That dedication to his performance in what is really an independent piece of work is commendable, showing early on his potential as a leading man.I'm not trying to undermine the story that is the heart and core of this film, I just believe it could have been filmed much better with less tedium to keep me invested. And for that I give it 6/10.

sharky_55

Consider how Steve McQueen captures a character's morning in his debut feature film Hunger. He uses extreme close-ups to gradually unveil the strict routine of getting ready to go to work. The man is silent and efficient; he tucks a napkin into the folds of his shirt like a scientist slipping into his lab coat, and observes the food as more or less one of the many requirements of the experiment. We see him silently check under his car for a bomb, and nervously glance along the empty street. A POV spies on him from behind a curtain - it's his wife, who we realise must also undergo the same agony each morning, gripping her hands tightly together as he turns the key in the ignition. He is Maze prisoner officer Raymond Lohan, who sits alone in the cafeteria and does not indulge in locker room talk. What we observe is the learned, robotic discipline of a man who cannot afford to make mistakes or become emotionally invested in his work. McQueen offers another close-up of Lohan against a mirror, a face straining in pain. And only after have we become invested into his life and curious of his struggles does the film reveal bloody knuckles, and the revelation that another person somewhere else is in much more pain than he is. By the time McQueen returns to the same sink half an hour in, our feelings and sympathies have been changed because of what we have witnessed. For years before hitting the big screen McQueen made short films, many of which were looped as exhibits in various art galleries and museums. These roots are evident in Hunger, which eschews classical narrative and storytelling and instead opts to wade into the vague and often ill-defined territory of art film, preferring enduring images over explanations. Much of the first half of the film is filled with moments that could define it: the camera swooping over the sh*t-stained walls and finally descending onto the dishevelled figure of Bobby Sands, the slow, silent burn of a hallway leaking puddles of the protester's urine, the way the world slows down as a wall separates the beatings and a lone, sobbing prison guard, singled out for his youth and naivety. It's brutal, senseless violence, as evidenced by the wall of sound and pain that the prisoners are marshalled through, or the way water droplets hit the face of the lens as they are forcibly bathed. But as much as McQueen strives for realism with his hand-held and guttural sound design, he can't help but aestheticise until it's not merely tragedy, but grandiose tragedy. Sands has had plenty of time, and turned his own faeces into a swirling piece of art. A hole in the cell window grating allows a shaft of white light to peek through, and a prisoner marvels at a fly that crawls upon his fingertips, not merely an insect but a symbolic representation of the freedom he craves. The treatment of the final days of the martyr Sands outdoes all these. The most discussed segment of the film are the two unbroken shots of the conversation between Fassbender and Cunningham, and for good reason. Like the better cinematic priests (think Brendan Gleeson in Cavalry, or any of the religious figures in Doubt), Cunningham is inserted not as a moraliser but as his own character, able to understand the complexity of the situation and offer his own perspective. Before they descend into rhetoric they engage in small talk, as Moran teases (he doesn't object to the sacrilege of the bible for a smoke either), and McQueen is able to make us understand that this is a routine they have endured before, and that through the seventeen minutes they always come to the same impasse. Moran sympathises and does not simply condone; although Catholic doctrine states that suicide is a sin, he is more interested in Sands' end goals and well-being. Forget the eternal suffering of your soul, what about your physical body and mind now? The pair are so well-versed in the exchange that they are on the verge of cutting each other off and jumping to the next line, or at least Cunningham's Moran is, sensing that his time is running out to save this man's life. Although much has been said about the symbolic meaning behind Sands' story, the visible result is that it paints him as a man of utmost conviction, able to shoulder the burden and responsibility of darker deeds for the greater good of others. But a story simply isn't enough. There is a lot more context here, and the film deliberately avoids engaging with the historical and political baggage of the situation, diminishing it to personal struggle. It depicts the increasingly fragile state of Sands' body, dissolving untouched meal trays onto each other, shoving the camera up close and asking us to cringe and avoid averting our eyes. McQueen doesn't filter Sands' last stand through the lens of a wider protest, or evoke the desperation of a group of men resorting to their remaining weapon, but reduces it to body horror, and renders the iconic visage of Sands into a withered metaphor for determination and conviction. Fassbender may be good at this, but he lacks the symbolic connection to the thirty thousand Irish residents who voted him into the Fermanagh and South Tyrone parliamentary seat during the hunger strike, so he's merely a physical body in decay. Not that this deters McQueen, however. In his close he all but denounces the stylistic precedent already established, and resorts to burying Sands in myth, superimposing flights of birds over his body, and bathing him in angelic light to transform his plight into rapturous martyrdom. No doubt Cool Hand Luke and Michelangelo's Pietà were consulted. And finally McQueen stumbles clumsily into formalism, revealing a younger Sands surveying the piety of the almost deceased older Sands, yet it almost seems to be a look of pity.

h-grotkasten

There are these moments of extreme brutality and of booming silence. The film feels like a perfect composition of nearly scientifically observation. Historical Information are gentle prepared in the story that there is no didactic moment. The film mentions to the empathy of all human beings, showing us colleagues, families, lovers and parents, this goes beyond understanding to reach pure feeling. The perfectly soundtrack and main theme is an impulsive understatement and also in perfect harmony as an piece of art itself; the soundtrack is not illustrating the pictures, it adds a rhythm, a way of interpret the Narration.

avik-basu1889

Although Hunger was Steve McQueen's debut feature film, I watched Shame which was his 2nd film before Hunger. His style looked unique and brutally explicit, but at the same time delicately artistic with the right amount of reticence to challenge the viewer. I was so glad to find the same positive attributes about his directorial work in Hunger too. He is one of the most recent directors whom I can easily call an auteur due to his signature style.Like Shame, Hunger is also at times a very tough film to watch. McQueen leaves absolutely no stone unturned to depict the brutal realism connected with the subject matter. The film on the surface is about the well known IRA member Bobby Sand's revolt and the hunger strike that he declared to force the British Government to grant the demands of the IRA. But to be honest, the film has very little to do with the politics of the matter. McQueen is more concerned with the people caught in the midst of this traumatic stalemate situation. He is concerned with the psychological and of course the physical effect this situation has on these characters. I liked the fact that McQueen effectively remains unbiased and neutral throughout the whole film. This neutrality is accentuated by the fact that he uses the perspective of different people belonging to either side of the tussle in the screenplay. So not only do we get to live these traumatic days from the point of view of Bobby Sands and his fellow prisoners, but also from the point of view of prison guards and riot officers. It is shown that the ones executing the strikes might have had to endure physical pain and torture, but the ones on the other side had to endure psychological torture too as well as the lack of security in public. One of the most admirable features of Hunger is the use of silence in the film. Almost 75% of the scenes are silent or with very little dialogue. McQueen allows the visuals and facial gestures of the actors to convey a lot in many scenes in the film. The makeup of the actors and production design are also meticulous with a lot attention to detail. The prison cells look as realistic and as dirty and grim as possible. The prisoners look equally worn out due to the harsh treatments handed out to them. The makeup is so detailed that even the teeth of the prisoners look worn out and decayed.There is a famous one take conversation scene in the film that goes on for about 15 minutes. The conversation in this scene is almost as serene as a Symphony. It starts out on a light note, then becomes heavy and heated and then ends almost poetically. When a single take scene which continues for such a long while works so well, all you can do is appreciate the acting and the writing that has gone into it. Talking about acting, Michael Fassbender sets the stage on fire with a jaw dropping performance. The film's subject matter and the content being too bold for the consideration of the Academy is the only reason I can think of which can explain why Fassbender didn't get an Oscar nomination for this role. He becomes the character of Bobby Sands through absolutely brutal method acting. He is unbelievably good.Overall I loved the film. The only sort of gripe that I have is with the ending. Although I liked the ending, but I wanted it to be a bit more effective and memorable. But having said that, it is a minor gripe. Hunger is not for everyone, it is disturbing, it is visually explicit and Mcqueen demands patience and attention from the viewer. But if you are prepared for all this, then you are surely going to have a rewarding experience.