movedout

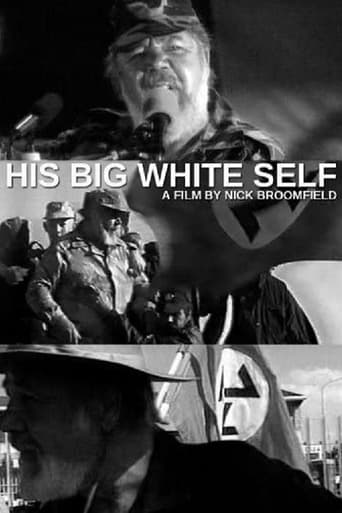

Nick Broomfield has an uncanny ability to unlock his subject's thoughts with key sequences of visual observations that without context might seem unremarkable. The maverick director follows up "The Leader, His Driver and the Driver's Wife" with "His Big White Self", a sequel of sorts that catches up with the titular trio of his career defining 1991 documentary that started off as an exploration of apartheid reign in South Africa that developed into a ghastly portrayal of a Nazi propaganda progeny (The Leader, Eugene Terre'Blanche) who rose swiftly and bloodily to power, and the lives of two close followers in JP (his driver) and Anita (his driver's wife). 15 years later and the portraits change somewhat, with the trio now broken up. But the creepiness of the country's still prevalent white power ideology and the willingness to martyr one's self for that belief remains. The only closure Broomfield gets from his rollicking by the intimidating Terre'Blanche all those years ago, is by tearing a page from Michael Moore's "Bowling for Columbine" playbook and conniving his way back into the Leader's household. And the only closure that we get to the hauntingly glazed over Anita of yesteryear is her transformed credo of believing integration is now the way forward, all subtly hitting home in the final scenes.

bob the moo

In 1991 Nick Broomfield's documentary "The Leader, the Driver & the Driver's Wife" sought to interview South Africa's AWB leader Eugene Terreblanche. Terreblanche's difficult manner make this a near impossible task and forced Broomfield to make a film about this challenge as much as about getting access to the man himself. However the film was a success and in some ways contributed to bringing down Terreblanche by exposing him as a buffoon and a figure of ridicule rather than a strong political leader for the future. Fifteen years later, Terreblanche has been released from jail after a short sentence and Broomfield decides to try and interview him now in the light of all the changes in South Africa since the first film.Some viewers have commented that it would have been a much more effective use of a film to pick up the story of South Africa since 1991 rather than recommencing the bun fight between two egotistical men (Terreblanche and Broomfield). Although this comment is valid, it should be noted that for the majority of the film, he actually does do the former pretty well and it is only in the final third that the film becomes more about the men than the country. The story of Terreblanche from the last film onwards is well told mainly because it focuses less on him and more on the wider political changes within South Africa and how he was merely one of many characters within that story. It is interesting stuff that is worth watching for.However the final third is annoyingly indulgent as Broomfield finally gets to his target, tricking his way into the man's house as part of a film crew professing to be shooting a piece about Terreblanche's poetry. Wearing a hat and big sunglasses, it is hard not to pick up the air of smugness as Broomfield tricks him and you can feel the urge he must have had to pull his hat off and reveal who he is. If he genuinely wanted to make a film that found out about the man as he is know it would have been a simple matter to send a crew to do the shoot and simply stay away. The fact that he didn't just exposes that what he wanted was conflict – not a story. His delivery of the rest of the film is good although I personally struggled with his dull narration and lack of personality.Overall then this is an OK film for the most part because it does providing an interesting look at the last 15 years in South Africa. However the presence of Broomfield and his quest to have a second go at Terreblanche is a distraction that eventually bubbles over into a pointless final thirty minutes. It must rankle Broomfield that Terreblanche didn't recognise him and, once he supposedly did, that he didn't make a big deal out of it! Interesting but hardly a worthwhile endeavour to try and pick over old conflicts.

paul2001sw-1

As South Africa's racist government came under increasing pressure in the late 1980s, there were many who defended it, rarely by directly agreeing with its ideology, but instead by spreading the idea that the country could not survive democracy: they painted a picture of deep tribal hatred among those of African descent, and pointed also to the inevitability of resistance to change from the privileged European minority. Eugene Terreblanche's AWB, a neo-Nazi militia army, was deplored by such commentators: but also used by them (and consequently talked up) to justify the continued existence of the apartheid state. In 1991, then unknown documentary film maker Nick Broomfield travelled to South Africa to met Terreblance. He discovered the man was a bully but also a buffoon, and when Terreblance refused to co-operate with him, Broomfield did something then rare: he put himself in front of the camera, filmed his own difficulties in making the film, and also his own (almost accidental) ability to wind up his subject. This is now arguably an over-used device (not least by Broomfield himself), but in this film, it really worked. In part this was because the appalling Terreblance was so instinctively unlikable that it was great fun to see Broomfield getting up his nose; but also because of the supporting cast Broomfield discovered, notably the affable (but fervently racist) J.P., Terreblanche's driver, and J.P.'s wife, a Sancho Pancha like figure, combining limited intelligence and basic common sense in equal parts. The resulting film ('The Leader, the Driver, and the Driver's Wife') made Broomfield's reputation, and arguably was the beginning of the end for Terreblanche's: he began a slow (and violent) descent to ridicule and ultimately prison.There's far less journalistic justification for this sequel, shot on Terreblance's release from prison (especially as Terreblanche, out on parole, was legally prohibited from giving political interviews during the period when Broomfield was trying to film him). But there's still some mileage in the soap opera of the three characters, and in the background, an interesting insight into how South Africa has changed (in spite of the efforts of the AWB). Even so, one wonders whether there might not be more pertinent stories to be told in that county than the contrived rematch between an egotistical journalist, and an even more egotistical maniac. Yet one watches with riveted horror at the peculiar sub-species of humanity we see on display here, thankfully further removed from power than when last caught on film.