roland-104

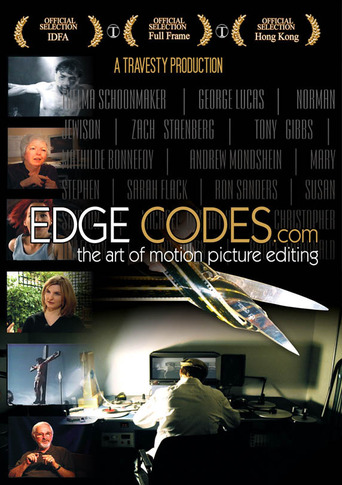

A singular and thoroughly edifying made-for-TV documentary about the craft of film editing. This movie is full to the brim with important information on its subject, organized more-or-less as a history of film editing. Here are some things we learn watching this movie. Editing is in fact the only entirely new artistic dimension devised specifically to make movies (i.e., writing, acting, costume, makeup, sets, music and photography were all established arts prior to the advent of cinema). Orson Welles said that, from his point of view, editing was not one aspect of film-making, it was THE aspect that mattered most.The use of edited cuts came as early as 1900 in France, and D.W. Griffith and Buster Keaton were among the first to elaborate the process of juxtaposing "visible" (jump) cuts for dramatic or comic effect, an approach that deeply influenced pioneer Soviet filmmakers like Vertov and Eisenstein. Their Soviet contemporary, V. I. Pudovkin, said that a film is not shot, it is built. Some later directors, like Hitchcock, Peckinpah, Scorsese and Oliver Stone, were in turn influenced by Eisenstein.Disjunctive editing came to be used for purposes besides dramatic effect, e.g., to create a sense of immediacy, like cinema verité (Godard's films, "Bonnie and Clyde," Tarantino's films), or for poetic effect (films of Alain Resnais). Rapidly sequenced, brief cuts – that began with MTV-style music videos and the early Beatles film, "Hard Day's Night" - became utilized commonly in feature films to enhance a sense of speed and urgency ("The French Connection," "Run, Lola, Run").Hollywood traditionally preferred seamless or "invisible" cuts in its effort to create an illusion of realism in movies The advent of sound was a huge stumbling block to the highly developed art of editing in the silent era. It would take until well into the 1930s for editing to be worked out in successful synchrony with dialogue, sound effects and music. Emotional and thematic continuity, as opposed to chronological continuity, have become increasingly important emphases in editing (Godard said that every film has a beginning, middle and end, though not necessarily in that order).Computers have reduced the complexity and time required for editing. And CGI has revolutionized film-making by making time itself much more plastic: speeding it up, slowing it down, even doing both simultaneously. The latest techie advance might be called interactive cinema, in which viewers themselves are in charge of their own editing (e.g., in sophisticated video games). Some see this development as a natural consequence of the editing we all now do in everyday life to cope with the constant bombardment of our senses.Throughout "Edge Codes," these and other developments are discussed by a host of talking heads and illustrated by numerous film clips. A number of gifted film editors take part, including Mathilde Bonnefoy ("Run, Lola, Run"), Dody Dorn ("Memento"), Sarah Flack ("Schizopolis," "The Limey"), Tony Gibbs ("Performance," "Walkabout"), Andrew Mondshein ("The Sixth Sense"), Ronald Sanders ("Naked Lunch," "eXistenZ"), Thelma Schoonmaker ("Raging Bull"), Susan Shipton ("Exotica," "The Sweet Hereafter"), Zach Staenberg (the "Matrix" trilogy) and Christopher Tellefsen ("Capote," "Barcelona").I have only one negative criticism of this fascinating film. It moves way too fast. There is enough material here for a two hour film, and I doubt that it would bore if the pace were slowed: e.g., longer clips shown, talking heads explaining things a little more, quotes in stills from famous filmmakers held longer on screen. As it is, I was only able to absorb most of the story by attending two screenings, and in fact I would have liked to return a third time to better understand some points that still zinged past me. My grades: 8/10 (high B+) (Seen at the Idaho International Film Festival, 09/29/06)