politic1983

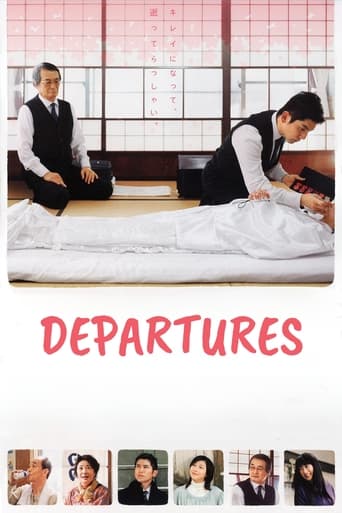

To paraphrase Nobu-san, our guide around the Okunoin cemetery at Koya-san: "In Japan, when we are born, we have Shinto rituals. When we die, we have Buddhist rituals. My mum got married in a church: New Caledonia." Buddhism in Japan is often associated with death. When one dies, the ceremonies that take place will often be Buddhist, but as Donald Richie explores, these could be as much for functional purpose as religious belief. But, obviously of course, no one knows what actually happens when you die. Or do we? It depends whether one is thinking about it from the perspective of the body or the soul. Yojiro Takita's Oscar-winning 2008 "Departures" see cellist Daigo's (popular hair model Masahiro Motoki) orchestra disband in Tokyo, leaving him doubtful of his talent and so his future. On a whim, he convinces his wife - with little coercion - into moving back to his small hometown in Yamagata, moving into the cafe his mother left him. Needing work, he responds to an ad with few details, but nice pay packets, and is immediately hired. It soon turns out that his job will be as an "encoffinfer", performing the Japanese noukan ritual of preparing the body before it is placed into the coffin (and then burnt, of course). Not an easy job, he struggles to cope at first and soon feels society's evil eyes once his new job is learnt: perceived as a dirty man for his handling of dead bodies. As the film progresses, so does his skill, winning over his doubters, including his wife, and finding what would appear to be a true calling: sending the bodies of the recently deceased on their final journey, coming to terms with some of the opportunities missed in life. Ten years earlier, Kore-eda Hirokazu released his second feature film: 1998's "After Life" (or perhaps its more appropriate Japanese title "Wandafuru Raifu"). Here, there after life probably isn't quite what you expected. Upon dying, you enter a somewhat New England-esque academic building, taking a ticket as if a doctor's waiting room. On this "Monday morning", you are assigned a counsellor who will pose you the situation: You have a week to choose the one memory of your life which you will take with you for eternity. This memory is recreated by a somewhat haphazard film crew, starring your good self, and the film is then shown to you in a cinema. Once viewed, you disappear for eternity, locked in that memory. Somewhat fanciful, the counsellors are all people that were either unable, or refused, to make the choice, and thus stay in a purgatory of administration and archiving, forever reliving Monday morning. A series of interviews are conducted with the various recently deceased, with now long-experienced - but still youthful in look - Takashi (Arata) given the task of counselling the man who married his fiancée after he died. Opening up some old wounds, Takashi spends the week contemplating his own favourite memories and finally makes his choice.The outlooks of the two films are quite different in their thoughts on death. "After Life" plays little on the sadness of having died. Those that enter are quite chipper, one must say, on learning that they've just kicked the bucket. As the Japanese title suggests, it's very much about celebrating the most precious, and wonderful, memories that we have of our lives. This could perhaps be down to Kore-eda's combination of actors and real-life ordinary folk discussing their favourite memories. Using his documentary skills, this is as much an exploration of memory than a mourning of death. "Departures", however, is very much aware of the sadness of death. Very reminiscent of Shunji Iwai's "Love Letter" in numerous ways, there are moments of sentimentality, tugging at the heartstrings, as well as plucking on the cello strings. Tears and emotion run throughout; the sadness of the families a key theme. A shot of a young child's body being prepared for their coffin accompanied by their smiling photo, hitting home the sadness in the simplest of ways. Though family tears and timely music perhaps dominate, going for more conventional crowd-(dis)pleasing. This is absent from "After Life", laying people's memories out before them to celebrate and chew on; more philosophical than sentimental. If death hurts those left behind, "After Life" is the memories of life for the deceased; whereas "Departures" is the final memory for the mourners. If we're looking at religion in Japanese death, however, "After Life" perhaps lacks any religion. Death is a bureaucratic process than a passing over. As seen in other films, such as Tim Burton's "Beetlejuice", death is likened to the administrative Hell on Earth of waiting rooms, form-filling and box-ticking. It's also a strange film in that it's very much of its time, serving as a time capsule, with the provision of lo-fi VHS cassette tapes for "clients" to view moments from their lives to help them in their choice. Surely the after life's administrative team can come up with a less archaic system! The recreations also seem to be more "human" and of the "real world", made to a seemingly small budget and limited time frame, far from Hollywood glitz and glam that many of the dead may have wished to achieve in the film of their life. A theme running throughout Kore-eda's body of work, this is perhaps as much a comment on the modern nature of memory and how we try to recreate it in permanent form rather than live in the moment of emotion. A comment as relevant now as ever. "Departures" features the religious ceremony of the noukan, placing the body in ritual dress, with accompanying make-up. But with even this dying out with the elderly, it perhaps reflects Richie's doubts as to the true religious nature of these "performances". Making the dead look their best is perhaps purely for aesthetic purposes, giving mourners one last perfect memory. Daigo's skill is very much in-line with Japanese aesthetics: The almost perfect folding with due care and attention of the deceased clothes, creating an intimate one-on-one with the body. "After Life", with its counsellors getting deep into their clients personal lives and directing them towards their perfect choice: Ones who struggle are probed to search deeper; those who go obvious, are challenged to look more inwards, creating an intimate one-on-one with the soul. Mono no aware, the Japanese sense of the fleeting nature of beauty and the impermanence of all things is alive in both films. Daigo's hard work and skill is - for want of a better word - in vain; the bodies made beautiful, only to be burnt at cremation soon after. "After Life" forces the choice of the single moment that defines a whole existence (and they only give you a week!). The last memory for the living versus the eternal memory for the dead; and perhaps a more Japanese sense of religion than any organised belief system.politic1983.blogspot.co.uk

beallen-49754

Departures is an international film from South Korea. The film is about a Korean man who works in the orchestra as a cello player, but when the orchestra goes out of business, the man, Daigo, is forced to move home. He ends up getting a job where he does the burial proceedings. He is hesitant at first, but ends up realizing that this job is his calling. Overall, this movie was quite good and very entertaining. I would rate this film a 4.5 out of 5. Although, this film is quite different compared to American films. For example it is very slow in comparison, so if you are looking for an action packed movie this is not the one for you. However, this is a very entertaining film and a must watch. It provides laughs, drama, and feel-good moments.

X Boy

A well written movie, which touches many themes most importantly dealing with death and watching others grief upon it. One side of it is very soft and touches our heart but on the other hand it is not as astonishing as we expect it to be. Story and even scenes are very predictable. Ending also could be seen from minutes away from it. Director has worked hard on the interior of Coffining but failed to bring deeper sentiments onto screen. Tsutomu Yamazaki's portrayal of a Boss who teaches the protagonist is the most fabulous quality of the movie. Actor actually work the role around and inside. Masahiro Motoki and Ryōko Hirosue are very convincing although camera sometime focused on Ryōko more then it needed. Her character as a devoted wife is well however it is not explored much. Ritual of coffining are filmed very good. The sub plot of protagonist's relation with his father was good but there could have been more about it. Over all a light hearted sentimental film.

Comptable

An American client, knowledgeable about Eastern ways, highly recommended Departures to me. It was nominated for an academy award for best foreign film, he told me. I read about the plot on IMDb, saw that it was about a Japanese man named Daigo who prepares dead people for funerals, and was immediately turned off by the idea seeing it. I told this to the client, and he said "The East doesn't think of death that way. No preconceptions allowed! It is not a death movie, it is a life movie".Having been gently but firmly rebuked, I returned to IMDb and read several positive reviews of the film. This time my impression was much different. I came to view this film with respect. It no longer appeared to be simply a "morbid" film, but a thoughtfully-made one, and representative of Japanese filmmakers' reputation for sensitive storytelling. With renewed interest in seeing the film, I told my client that I'd see it when I have time. I started watching it three weeks later.Not only did I watch it, but I managed to persuade my wife to watch it with me. Initially, she was repulsed by the sight of dead people being prepared for burial or cremation, and refused to continue watching the film. However, she overcame her disgust when I starting watching the film myself from where we had left off, a week later, and when she heard the beautiful music of the film's soundtrack. We saw the rest of the film together, and we both liked it. My wife was charmed by the sight of Daigo playing the cello, especially when he played on the hilltop. He was an orchestra of one. Daigo had a job playing the cello in an orchestra, but was forced to give that up when the orchestra was disbanded. He answered a help wanted ad, thinking he was applying for a job as a travel agent. Instead, he was hired to be a ritual mortician, a job which he at first detested and which made him sick. The pay was very good, though.The artistry of this film must be seen to be believed. Here are a few examples: there's a scene in which Daigo applies lipstick to the lips of a deceased wife and mother during the "en-coffining" ceremony: her husband and daughter express their heartfelt thanks to him after the ceremony for making their beloved wife and mother, respectively, appear more beautiful even in death. Another example: an old man prepares to cremate a deceased bathhouse owner, an important member of the community, while explaining his role as a gatekeeper to the next world to Daigo's former orchestral comrade. The comrade had reproached Daigo in front of the comrade's wife and child for doing such undignified work, and can now see the value of Daigo's work. The final scene is the final example and the ultimate climax. It was in that last scene that I most saw the resemblance to one of the best Ozu films a Dutch reviewer on IMDb mentioned in his review, even though I haven't seen an Ozu film. The scene is poignant; it is beyond astonishing, it is beyond extraordinary. It is magical.Throughout the film, the music is as moving as it is beautiful. It serves to reinforce the film's message that en-coffining is an honorable profession, one that helps the loved ones of those left behind find solace, even joy, despite the loss of their dearly departed family members and friends. The acting is superb in the film. I could feel the sincerity of the characters as I watched them go about their lives. Daigo, Mika, and Sasaki, especially, conveyed genuine feeling with their expressions and actions. As the actor who plays Daigo, Masahiro Motoki, had an enormous interest in the subject of the film – in fact he wrote a book on the relationship between life and death – this added considerably to the credibility of the film and his role in it.What is most significant to me about this film is the way it shows how one's choice of profession affects one's life in important ways. This film is about death, but it's even more about life and the effect that death has upon the lives of those who make it a profession, as well as those they care about. Moreover, there is beauty, even in death.Japanese culture is depicted in a realistic way. As an example, when my stepdaughter, who spent time in Japan, came to visit us, I told her about Departures, and she told us about the bathhouses in Japan. The bathhouse in Departures matched her description. The Japanese values of respect for one's elders, tradition and nature are much in evidence in this movie. The film accurately portrays the stigma involving death in Japan: that death in Japanese culture is thought to be a source of impurity and that those who work closely with the deceased, such as morticians, are considered unclean. It is this stigma which Daigo strives to overcome in his new career. I urge you to see Departures. Although it doesn't explore the religious side of the Japanese funeral ritual, it is nevertheless an artistic and reasonably authentic portrayal of its place in Japanese society. It's very likely that you will enjoy Departures, or at least some aspect of it, and that you'll find much meaning in it. The care with which this film was made will be become apparent to you as you watch it. It is truly an antidote for the crassness of the modern Hollywood film tradition, with its puffery and special effects mania. It is an antidote, for that matter, for the materialistic culture that we cling to so desperately in the United States.