pat_batman

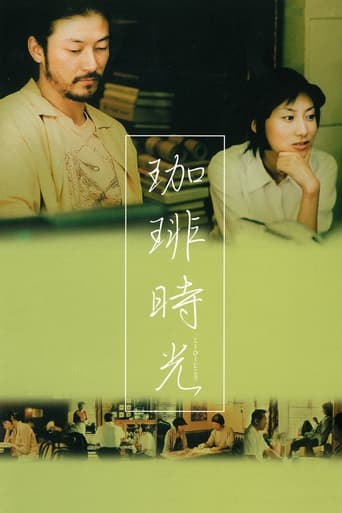

Textures. The Layering of scenes. Density with purpose. Filling a shot to the brim with material, lines, shapes, forms, movement. Hou Hsiao-Hsien's Café Lumière is a triumphant lense into the cramped spaces of contemporary Japanese life, albeit through the dispassionate, voyeuristic lens of a Taiwanese man. Scenes evoke the visually dense interiors of Yasujirō Ozu films such as Tokyo Story (1957) or his "Seasons" series; who Hsiao-Hsien acknowledged he was paying homage to.Japanese cinema stalwart Tadanobu Asano as Hajime offsets Yo Hitoto as Yoko, a youthful writer, pregnant amidst concerns from her parents about her professional and marital life; or the expectations of adulthood juxtaposed by the groaning of an older generation, an oft used theme in Ozu's work. Meanwhile her quest to learn more of Jiang Wen-Ye, a Taiwanese Composer, for a new book she's researching takes her through the intricate landscape of modern Japan. Asano provides interludes of stunning earnest, as the shop owner-cum-audiophile who records the numerous metro trains with his portable boom mic. His sporadic appearances and interactions with Yoko have a realistic rhythm to them, a sort of awkward warmness that permeates throughout the film, as they search for information on Wen-Ye.Familiarity with Ozu helps contextualise the film for its broader themes, but the focus and poise of Hsiao-Hsien is distinct and his foreign eye catches much of the unsaid, unheralded beauty of the moment. As the final images of trains intersect and Hajime is slowly recording the whirring cacophony of passing engines, we realise that life is to be lived; by recognising the moment and enjoying the visceral, audible, vibrations of the myriad means of existence around us.--Rave Silo

dromasca

One needs to watch carefully and attentively this film which is not easy, but reserves a lot of interesting and beautiful things, despite a lack of story or actually despite the story not being in the focus of the director. It is a reverence by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-Hsien to the Japanese master director Ozu on the 100th anniversary of it's birthday. However, it is not a film of quotes, but rather a travel to research what is left of Ozu's world in the Japan of today, and the connection between Taiwan and Japan in the world that was once Ozu's.There are a lot of trains in this film. This passion for railways may be taken from Ozu, but in 'Cafe Lumiere' about third of the film happens in trains or railway stations. A memorable sequence describes the universe of metropolis with trains entering and exiting tunnels, another shows in a computer generated drawing an universe of trains, squeezing a minuscule uterus and a child - maybe the expected child of Yoko, the principal character of the film, or maybe symbol of fragility of our existence in the modern world.Another fantastic scene of cinema presents the house of Yoko's parents at her arrival. We can see just Yoko's mother in the last plane preparing food in a lit kitchen, then the kitchen is framed by the house guest room, which is at its turn framed by the doors and external walls of the house. Then the sound of a car is heard, and we more guess than see the arrival of Yoko and her father reflected in a glass door. Four planes in the same frame, with no move of the camera.The story is minimalistic, and whoever looks for action risks to be deeply bored. The actors perform so well that the word 'perform' is not not adequate here, they live the characters. They seldom interact, they never stare in each others eyes, but rather look in different planes, same as the trains movements never intersect. They do however care for each other, and the story is a delicate one of familial solidarity and deep friendship in a world that may look frightening. These characters could have been part of a film by Ozu.

perfect_circle21

I've given 'Kôhî jikô' a low score not because it was a bad movie, but because it doesn't do anything worth praising.I've not seen any of Hsiao-hsien Hou's work before, but for the uninitiated (me included) 'Kôhî jikô' is advertised as a homage to Yasujiro Ozu. (A Japanese director whose last film was way, way in 1962) The film is an extremely sparse work...containing very little dialogue, story, music or emotion.Yo Hitoto plays 'Yoko' a jobless, wandering character who spends her time in her local coffee shop or loosely investigating a Taiwanese composer she likes. Tadanobu Asano plays her friend, who works in a cd shop and occasionally indulges his otaku interest in trains. And that's about all it.We watch as Yoko drinks coffee alone...walks around...waits for a train...catches a train...falls asleep on the train. The kind of mundane reality anybody in Japan can see on a daily basis. Hou captures these ordinary moments of these characters life, but without any meaning to these vignettes it's an entirely pointless film to make or watch.

Chris Knipp

A girl who is pregnant is visited by her parents and may not know who the father is. Her main friend works in a bookstore and records train sounds as a hobby. For this viewer, "Café Lumière," which had been long anticipated, was disappointing when finally seen. It didn't leave very strong impression and a week later it had almost faded from the mind. It seems to me that the resemblance to Ozu, whom this was commissioned by the producer as a sort of homage to, is superficial indeed. Ozu can make you cry. This, despite its Ozu-like structure, leaves you feeling rather blank. Perhaps this is because it's essentially about people avoiding real contact with each other. That's not the same as being reserved. In fact it's extremely different. People who are shy and reserved, as Ozu's characters tend to be, may very often care very intensely. The impression is that these people devised for Hou's version of Japan just don't ultimately seem to feel very much. If this is how things are now in Japan, too bad; but would Hou really know? He's Chinese. He has even admitted in interviews that culturally he was a bit out of his depth in coming to Japana to make a film. Despite very assured style, the deadpan story has no pulse. This is more a perversion of than homage to the great Ozu. Another commentator has said Café Lumière "may be the film that Ozu would have made if he lived in the modern age." It may be; but I don't think so. And if it were, then it is as well that Ozu did not live in the modern age, because he would have ceased to be Ozu.As I have said recently in another context, Hou doesn't always hit it, but when he does he flies to the moon. Hou can't make a movie without stylistic and visual elegance, and "Café Lumière," with its cool tranquility and measured pace and its delicate light, has those qualities. But he didn't make it to heaven this time. In the second part of his recent "Three Times," he did: all the way to the moon. So he can still fly, but this conscientious, measured effort plods.