Scorpio_65

I am a huge Robert Altman fan and, I have to admit, I really hated this film the first time I saw it. Most of his films have fairly slow paces which can sometimes be enjoyable and can other times be challenging; however, my initial reaction to the pace of this film was incredibly tedious, boring, and *really* tried my patience to the point where it was not an enjoyable experience in any way. So, I watched the whole thing, went to bed, then watched it the next night after reading a bit of historical context into Buffalo Bill. It helped a *great* deal with the multi-tasking of following some the historical context of what was said in the film while simultaneously enjoying the individual subtleties of the cast's improvisation. The eclectic cast is really wonderful even at their most subtle as in most Altman's films. I particularly enjoyed Will Sampson, Geraldine Chaplin (my favourite role of her's here), Burt Lancaster, and, of course, Paul Newman...even Harvey Keitel was great. If anything, one should take in the cast of this film and I encourage anyone to do a Google search of some kind just to get a bit of historical context of Buffalo Bill before watching, as I did, if you don't know too much. Certainly, by no means, is this film up to par with other Altman masterpieces like 3 Women, but worth two viewings if you are interested in seeing most of his films.

Bill Slocum

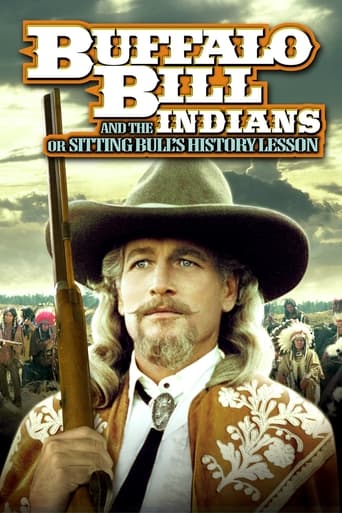

The best part of "Buffalo Bill And The Indians, Or Sitting Bull's History Lesson" is the first ten to 15 minutes. We join a Wild West show rehearsal circa 1885, and watch as its staff work at creating a show that takes itself a little too seriously. The feeling of observing a real, living thing comes across, only a bit funnier than reality."Tell Joy not to get on the horse in back," mutters the show's MC, Salisbury (Joel Grey) regarding an actress playing a white woman abducted by Indians. "It looks fake. We're in the authentic business." Later, Salisbury shoots down a band's idea of real frontier music as "too Ukrainian."All this is easy to miss when so much is going on at once, while horses nearly run down a pedestrian in the foreground. This is a Robert Altman film, after all, or "Robert Altman's Absolutely Unique and Heroic Enterprise of Inimitable Lustre!" as it bills itself.As Jeff Lebowski might say, Altman's not into that whole brevity thing here. A two-hour extravaganza, "Buffalo Bill" stars Paul Newman as Bill and makes its points about how show business and American mythmaking became one with repetitive, haymaker swings. The end result is a comedy that's not that funny and a social statement that's not that convincing, but Altman's secret sauce of a busy camera and piquant performances makes for a pleasant if shapeless affair.Newman's something of a disappointment, giving less a performance than a caricature. I get the feeling he was directed by Altman to just play a slightly older and more pompous Hud with a goatee. He fills out Bill by drinking rotgut from a schooner, loving and spurning a succession of opera singers who never stop singing in frame, and watching over his stardom with a kind of prissy defensiveness that belies his self-cultivated frontier image. He can be a joy to watch still, working his eyes and playing to his mirror, maybe winking at the audience about what they expect from him as both Bill and Paul. If only he had better material."You ain't changed, Bill.""I ain't supposed to. That's why people pay to see me."There's also the business of his dealing with the Wild West Show's newest star attraction, Sitting Bull (Frank Kaquitts), which gives the story much of its social perspective. Bill thinks of Bull as an ungrateful pet who needs cultivation in "the show business," while Bull thinks Bill sells lies in the guise of history. Hence the "history lesson," which feels shoehorned in from a more socially committed source play. Altman wants to tell that story, but most times he'd rather have fun with the show-making part, and while you are watching this, you wish he'd cut loose and do just that.The film succeeds in short bursts, though the eccentric casting choices Altman throws at you here don't work as well as they did in his other films. Geraldine Chaplin as Annie Oakley? Harvey Keitel as Bill's nerdy nephew? Some Altman vets like Robert DoQui and Allan F. Nicholls are barely in the film while stars like Newman, Keitel, and Burt Lancaster get longer spotlight time. John Considine is fun as Annie's flinchy husband, "the handsomest human target in the West," though that running joke, like so many others, is plugged more times than one of Annie's nickels. I was impressed also by Kevin McCarthy's publicist character, not only for the juiciness of his grandiloquent performance but the magnitude of his handlebar mustache."Buffalo Bill" takes a lot of time saying a good deal less than it thinks. But the spectacle of "the show business" and the minor bits of Altman kookiness and sardonic commentary around the edges keep this a diverting if underfilling entertainment.

classicsoncall

I'll have to dig into the true story of Buffalo Bill Cody, as this revisionist Western paints a decidedly one sided view of the pioneer legend, with no redeeming qualities that I can remember from the picture at all. His condescending demeanor is illustrated by the assignment of a 'colored' stand-in for Chief Sitting Bull, and the shoot 'em up contempt he has for an unfortunate canary. To his credit, Paul Newman does an exemplary job of pulling off that portrayal, but there must have been some good qualities Cody might have had, though they weren't on display here.Will Sampson has always been a personal favorite, and I was blind sided as I'm sure most viewers were when it's revealed he wasn't Sitting Bull. I'm curious now how one time actor Frank Kaquitts managed to land his only screen role as the legendary Chief of the Hunkpapa Sioux. The disappointment for me came at the end of the picture when Sampson reprised the role of Sitting Bull for the Wild West finale, surrendering any integrity he might have had as spokesman for the Chief.What I liked about the story was how Buffalo Bill kept being put in his place by circumstances beyond his control, even when surrounded by an army of yes men. You would think he'd have been a more principled individual, but it appeared that every decision was based on promoting the gate. In that regard, probably the most interesting aspect about the movie is it's take on the beginnings of 'the show business', as Bill and his partner (Joel Grey) liked to call it. Can you picture 'Entertainment Tonight' back in the late 1800's paying tribute to Pahaska Long Hair and Annie Oakley as the celebrities of their day? Who knows how big their legends might have been if Al Gore had invented the internet a hundred years sooner.

tieman64

"In so far as they cannot be assimilated by modern culture, the wild peoples will have to disappear from the surface of the earth." – Karl KautskyPaul Newman plays Buffalo Bill, a one-time soldier who now runs a successful Wild West Show. Bill hires an Indian warlord called Chief Sitting Bull to guest star in his show, but to Bill's annoyance Sitting Bull proves to be a decent and honourable old man rather than a murderous savage.Bill attempts to get Sitting Bull to re-enact various battles between cowboys and Indians, but Sitting Bull refuses to be portrayed as a caricature. Rather than act out Custer's Last Stand as a cowardly sneak attack initiated by red skins, Sitting Bull instead requests to portray the massacre of a peaceful Sioux community by marauding US Cavalry soldiers. What follows is a battle of myths. Sitting Bull wants to portray his people as the victims of genocide, whilst Bill hopes to portray himself (and by extension the history of White American settlers) as a noble hero and the natives as brutal savages in need of either expulsion or civilization. Bill's history is wrong, of course, but he is the victor as he owns the show, controls the money and knows exactly what his white audience wants. His myth gets printed.And so these various themes – politics, show-business, the commodification of history, the blurring of fact and myth – play out in typical Altman fashion. And like most of Altman's films, this is a giant ensemble piece which takes place in a self-contained environment (the ropey confines of a Wild West Show). Elsewhere Altman's camera glides through his landscape, floating from character to character, various narrative strands gently picked up and followed. It's a graceful sort of film-making, Altman less concerned about delivering spectacle, than gently exposing the conditions under which such spectacle thrives. On the most basic level Altman deconstructs Old West iconography, presenting the cowboy as a show-biz creation who is himself duped by the very myths he bolsters. Altman's Buffalo Bill wears a wig, can't shoot straight, can't ride a horse and requires all his mock battles to be rigged in his favour, and yet he's constantly proclaiming himself to be a grand hero and seasoned man of the west. The film's great joke is that we the audience are so seduced by Paul Newman's star persona, his charisma, the way he commands his on screen lackeys, that we don't quite notice how much of a bumbling idiot he is. The film's characters go out of their way to illustrate this mightily confused blurring of reality and illusion. Altman makes us aware that his film is populated by mere actors and implies that both the personal and show business personae of Buffalo Bill are equally fraudulent. As such, Bill is constantly looking at reflections or portraits of himself, his personality always distorted. Altman also exposes the symbiotic relationship between show business and politics. Upon seeing President Cleveland, Bill exclaims "There's a star!" and of Sitting Bull he says, "If he wasn't interested in show business he wouldn't be a chief!" Later it is revealed that President Cleveland consults an aid before speaking and that Bill has someone else write all his material, both men the unwilling orators of a national myth. Altman then implicates both the audience and the public in the writing of both history and show business. "Truth is that which gets the most applause," one character correctly remarks. The show that is most seen, most palatable, most digested by the masses, is the show that is embraced as historical fact. Nations are built on noble lies, Altman says, and art exists to either propagate or challenge these national myths. This is made most direct when, in the film's final scene, Bill studies a portrait of himself on a white stallion. "Is he sitting on that horse right?" Bill asks, then turns to the camera. "If he's not sitting on that horse right, how come you all took him for a king?" Altman's point is clear. The facts, the cinematic clues, that Buffalo Bill was a fraud were always there. We just chose not to look. The implication is that seeing is always a matter of choice, perception a function of the needs of a dominant ideology. Altman is challenging the audience to see the flaws, to see our history and our present as it really is. And so Altman demonstrates that history itself is increasingly becoming another commodity of capitalist economy; history then is not a Truth, but a matter of choice, able to be traded, bought and sold. The resulting alienation from its process of creation and from the interconnection of its events leads to a loss of truth which only performance can replace. Tellingly the film ends with a photograph - a staged event of a staged event - the audience asked to recall an earlier scene in which this shot was composed. Without this prior context, anyone stumbling upon the photograph would assume that a tall and muscular Indian, carefully positioned by Buffalo Bill to draw attention away from the old and timid looking Sitting Bull, is the real deal. It is this loss of context, of objectivity, that Altman is ultimately condemning. History is like a photograph, deliberately composed, and so without context values may be constantly reformulated according to the narrow requirements of the dominant ideology. Compare this to the end of Brian De Palma's "Redacted", in which a soldier's smile is recorded as truth, when in fact it is forced, a lie and masking something far darker. Altman's film amounts to the same thing, though his photograph is then sold and paraded about as political currency.8.9/10 – Masterpiece. See Hany Abu-Assad's "Paradise Now".