jzappa

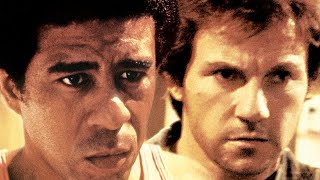

The world is represented to us through stories from parents, books, friends, conversations, groups at school, around the playground. Not all of our stories explain the world, but provide us with an easy, unconscious, involving way of making sense of it, sharing that with others. Its universality underlines its intrinsic place in human communication. This is why stories should be personal, tell the truth, and few narrative films have ever been as penetrating about how the working classes are manipulated by the system, or as affecting, especially in the grim results of each man being pitted against the other by corporate and governmental pressures, as Paul Schrader's Blue Collar, a pure rush of aggressive humor, relentless dramatic turns and real-world atmosphere.Schrader's known best for his work collaborating as screenwriter on many of Scorsese's most poignant films. If you watch Blue Collar expecting a Scorsese-style film, depending on your reading of Scorsese's work---and a wide array of certain men respond deeply to it---you'll be charmed in somewhat the same way. Schrader at the wheel, however, holds shots much longer, his compositions much wider, which could be attributed to his influence by Ozu. His editing style is less restless, but more direct: The coming shift shows up. Soundtrack music of hammering insistence, steering the force of the machines stamping out car doors. And somewhat like a Scorsese film, but in a more straightforward, cut-and-dried way, the images are cut to the music. The camera brings us into the innards of an automobile factory, close enough to virtually smell the perspiration, squint our eyes against the sparks from welding torches. Blue Collar's about life on the Detroit production conveyors, about how it makes men weary, confines them to a permanent deferred credit arrangement. It's a bitter, firebrand-progressive movie about the Venus flytrap ensnaring workers between the big industry and big labor that digest them. Three workers, pals on and off the job, are each no better or worse off than the other. They work, drink afterward in the neighboring bar, go home to mortgages, bills, kids who need braces. One day they get sick and tired enough to decide to rob the office safe of their own union. What they find there's merely a few hundred bucks, and a ledger that looks to include the details of illegal loans.They're played by Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel and the under-appreciated Yaphet Kotto. They're all three in top form. Apparently according to Schrader, none of the them got along during production. Fistfights between takes were not uncommon. Nevertheless, Pryor, especially, is a wake-up call: He's been engaging in a lot of movies, though pretty much invariably as himself, his smooth tongue doggedly in cheek, running comic variations on the gist of his dialogue. This time, harnessed by Schrader, he unleashes a taut, persuasive performance as a family man, his dressing-down of a union rep and an exchange with an IRS agent definite masterstrokes. Kotto plays his opposite, an ex-con who throws all-night parties comprised of sex, booze and weed. Keitel is their white friend, constantly behind on his loan payments, who comes home one day to see that his daughter's attempted to curve paper clips over her teeth to make her friends at school think she's got the braces she should have.Schrader goes for a comfortably crude humor in their scenes: The movie's at ease with itself; we get the exact nature, characteristics of their community. We get their friendship, too, which confronts what the movie tempestuously and very very directly indicts: That trade federations and corporate management both implicitly work to set the wealthy against the underprivileged, black against white, old against young, to divide and conquer.The heist originates naively enough when Pryor orders that his locker be fixed. The union reps (one played by fine character actor Lane Smith) are apathetic towards Pryor and virtually everybody else. So Pryor barges into the office of the grizzled Santa Claus-looking union head who was a rebellious progressive himself, once, decades ago. And as the refined politician's handing him all sorts of subterfuge, Pryor sees the office safe, becomes inspired. The larceny itself strikes the right pitch between potboiler and in some sense a silent farce. Then, the movie's rage starts to broil. When the threesome find that the ledger may be worth more than the money, they're divided between using it for blackmail, or revealing the skimming of their own union. Schrader slowly unravels his complete picture in the second half: A hearty, flourishing camaraderie abruptly embitters. The system deepens divides between them, as Pryor's furnished with a union job proposal, Keitel becomes an FBI rat, Kotto evinced to have little to no use for the capitalist machine in a scene of shocking, agonizing voltage.It took a lot of balls to make Blue Collar, particularly to track its turning points through to their inexorable outcome. It could've backpedaled in its last half hour, given us an easy, tried-and-true Hollywood finish. This isn't a liberal film but a radical one, one I'd bet a slew of assembly-line workers might see with a jolt of acknowledgement. It also took a particular cinematic penchant to make it flourish with equal banter, compassion, and tension. It's both pleasure and prosecution, functioning equally well in its humanistic layers as with its concepts. After penning Pollack's The Yakuza, Scorsese's Taxi Driver, De Palma's Obsession, Schrader was able to summon that he helm his own material, and Blue Collar is an impressive, surprising launch, taking risks and succeeding with them.

ametaphysicalshark

"Blue Collar" opens with a masterful title sequence which introduces us, quickly and effectively, to the harsh world our characters reside in and to the nature of the conditions in the factory they work in. The opening sequence is set to Jack Nitzsche's "Hard Workin' Man", introducing blues music to us right off the bat, music that not only makes up basically all of the music in this film but can be seen as a motif or even a character in the film. It's amazing how confident and mature Paul Schrader is as a director at this point. Of course, Schrader had already written the massively acclaimed "Taxi Driver" by 1978, but contrary to what one might expect it's his confident and sure handling of the pace and mood in "Blue Collar" that is truly the highlight of the film, not the screenplay penned by Paul and Leonard Schrader, granted the screenplay is in itself quite terrific. Schrader is already a mature director who understands the rhythm of a film.Going back to the use of music in this film, it isn't so much the score itself by Jack Nitzsche (which is, don't get me wrong, solid blues) that's impressive, it's Schrader's handling of the music and sound in general in this film that makes it work so well. First off, the choice to go with a blues score is inspired in itself, as the nature of the music so perfectly captures what these characters are going through. In addition, the score is most noticeable during scenes where the film appears to be commenting on the futility of the characters' struggle and the misery of what they're going through. Where many films would use music to 'enhance' big, dramatic scenes, Schrader's "Blue Collar" makes the wise decision to use it during low-key scenes. There are several scenes that don't feature any music at all, these being some of the more important scenes. Note the scene where Smokey gets trapped in the paint room, absolutely no music, just the cold sound of the machinery (expertly mixed, might I add), which is far creepier and more effective than any score could be at that point. Similar use of sound occurs a few minutes before the end when Harvey Keitel's character Jerry is being chased.The acting here is uniformly superb with Keitel possibly giving his best performance (or at least one of them), and Richard Pryor offering what must be recognized as one of the finest performances of the 70's by anyone. Really, who knew Pryor had this sort of skill when it comes to dramatic acting? Yapphet Koto, a beloved character actor, does a fine job in rounding out the cast for the main three characters. Again, Schrader must be credited for directing his actors so well. It's well-known, of course, that the three leads hated each other and actually broke out in fistfights between takes on occasion. Perhaps that created a sort of demented chemistry between them.The screenplay by Schrader and Schrader (Paul and Leonard) is a fine, fine piece of writing, sort of the daytime factory-worker version of the crude-yet-poetic "Taxi Driver" screenplay. Oddly enough, it's also the source of the few major flaws in this film, as it can come across as fairly heavy-handed in certain scenes. If there's one thing I'd definitely do differently with this film, it's the final shot, which would have been terrific had this been a comedy.All in all, a great film in its own right and especially impressive as a directorial debut from Schrader. Very memorable.9/10

sputnik17

Ever worked in a sh***y car factory?Ever been on strike?Ever been f***ed over by your boss AND your union?No?Well,writing as someone who has experienced all the former,let me tell you that BLUE COLLAR is the truest story of car making,sweat drippin',metal bashing,production line workin' anger your gonna see.I'm writing this 28 years after its making,and I can honestly say that at no time before have I ever seen the frustration of working class men so accurately and painfully displayed.I find it hard to comment on this film objectively,because,as I have said,I've witnessed it for 11 years.From coffee machines stealing money and ball breaking foremen,to friendships destroyed over ambition and men pushed to breaking point,this film is a true reflection of life on "the Track". For most it will be gritty drama,for others it will be all too familiar...