Danusha_Goska Save Send Delete

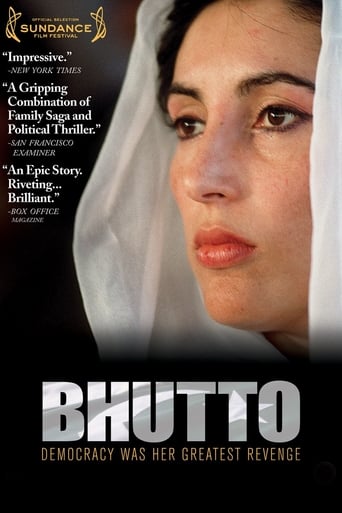

I've always been fascinated by Benazir Bhutto. It's hard not to be. She was certainly stunningly beautiful. But it's more than that with Bhutto. She was a woman who was elected prime minister of an officially Islamic nation. You could read her calculating intelligence and her steely determination on her exquisitely beautiful face. You can also read there the great tragedy that stalked her family, and her nation. Bhutto also gave off an air of idealism. Bhutto believed in something bigger than herself, something for which she was willing to sacrifice her life. Sacrifice she did – Bhutto endured prison, and returned to Pakistan from exile knowing the nation she loved so much would probably kill her. It did. But there's great complexity in Bhutto's life, as well. She did some things that were not at all admirable. Her own niece accuses her of murder. The talking heads in this documentary compare the Bhutto family saga to a Shakespearean plot or a Greek tragedy. It's actually more high opera. Benazir Bhutto was a great beauty who renounced a personal life so she could pursue politics. She realized she would need a man to get over in a Muslim country, so she submitted to an arranged marriage with a very handsome playboy polo player. Bhutto stated publicly that were she not a woman politician in a Muslim country, she would not have submitted to an arranged marriage. Muslim norms prevented her from meeting a man she might fall in love with on her own. As in an opera, she fell in love with the husband her mother picked out for her. Some say he betrayed her by accepting graft; others say this is a political smear. "Bhutto" the documentary certainly presents the drama of Bhutto's life. Talking heads include her personal friends, her husband, her children, her sister, and her niece. Her friends speak of Bhutto in the most glowing of terms. Exactly because this is the realm of politics, one cannot take anything that anyone on screen says at face value. One thing I wish this documentary had offered was a reliable navigator, an authoritative voice helping me to sort politically expedient comments from solid facts. The film does provide contradictory voices on the question of corruption. A New York Times reporter insists on the accuracy of the Times' charges of the Bhutto family's corruption. Bhutto's friend insists that her lifestyle was not that of someone with the alleged unlimited funds. Another friend points out that Asif Ali Zardari, Bhutto's husband, was kept in prison but never convicted. There's a lot of tragic and regrettable history up on the screen. Pakistan gets a nuclear bomb, fights wars with Bangladesh and India, supports the Taliban, hosts Osama bin Laden. The Bhutto family is depleted by one assassination after another. Benazir keeps trying to get and keep power in Pakistan. Her friends insist that this is so she can build schools, end polio, and provide clean water. Bhutto had other noble goals. She wanted to avenge her father's assassination. She stated that "Democracy is the best revenge." She wanted to serve as a liberatory example to women and girls – while maintaining a public, feminine, nurturing face. She wanted to reconcile Islam and the West, to prove that Islam and democracy are compatible. The documentary does not linger on horrific aspects of the Bhutto legacy. The Bhuttos, father and daughter, made sure Pakistan developed nuclear weapons and shared that technology with North Korea. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was president of Pakistan during the war with Bangladesh, a war that included massive human rights violations so severe some labeled them "genocide." Bhutto declared Ahmadis "non-Muslims." There was deadly persecution of Ahmadis in 1974, under Bhutto. Benazir Bhutto recognized the Taliban in Afghanistan. She didn't repeal the hudood ordinances. Pakistan has lots of problems, problems the United States didn't cause. The talking heads in "Bhutto" insist that America's eagerness to stem the spread of communism screwed up Pakistan. But the US was involved in Poland during the Cold War, and Poland did not turn into a country where any prominent person, from Benazir Bhutto to a schoolgirl who just wants to learn to read – Malala Yousafzai – risks assassination. America didn't cause the huge gap in literacy in Pakistan between women and men. It doesn't promote child marriage or hatred of Ahmadis and Christians. Benazir Bhutto tried to open schools and end polio. Pakistan's schools are now "ghosts" that take government funds and education no one. Polio workers are shot by Muslims who insist that the polio vaccine is an American plot to sterilize Muslims. Concerned observers often point out that India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh were all created at the same time from the same raw material: the former British subcontinental empire. India is doing relatively well. Pakistan is floundering. Why? One possible explanation frequently offered by geopolitical observers. Pakistan was founded as an Islamic state. Bhutto is shown taking the oath of office; she must swear that she is a Muslim in order to do so. Maybe Pakistan would be better off if it had not been founded on Islam. Maybe Pakistan would be better off if it were a secular state.Maybe Benazir Bhutto, for all her intelligence, was on a doomed mission. Maybe Pakistan as it exists today is not reformable. Maybe it would take an Ataturk, a Mao, or an Ann Coulter (invade their countries, kill their leaders, convert them) to make Pakistan a place where democratically elected leaders who improve their citizens' lives can peacefully hand over power to a succession of other democratically elected leaders, all of whom die peacefully in their sleep.

David Lewis

I attended a screening of Bhutto at Montana State University in October, 2012, and a discussion that followed with producer Mark Seigel. The first question posed by a young man after the conclusion of the film said a lot. Inspired by an underlying message in the film, he proposed a scenario in which problems in Pakistan were a result of American foreign policy. Seigel immediately affirmed that point of view in his response, and at the outset of his talk made a reference to Mitt Romney that seemed out of place. Seigel is a hard core Democrat, having served as Executive Director of the Democratic National Committee, and this may be important to a few key assertions in the documentary that stem from ideology rather than history. Bhutto is worth watching and provides plenty of biographical background on one of the most fascinating and courageous leaders of modern times. One wishes though that erroneous assertions that have little to do with her life were omitted, such as the urban legend that the U.S. backed Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan in the 1980s during the days of the Soviet invasion and occupation. That is simply false. Bin Laden was a Saudi, with Saudi money, and was probably not even physically in Afghanistan in those days, but in Pakistan, and not part of the indigenous Afghan non-Arab fighting force that the US was supporting. The film though shows Bin Laden, using much later footage, in that context, as if from Afghanistan in the 80s—a blatant deception. Simple fact checking would have dissuaded an objective filmmaker from including this bit of nonsense in the production, and I include this assessment as a former associate of the Committee for a Free Afghanistan who spent time with Zia Massoud in the mid 80s, brother of Ahmad Shah Massoud (the Afghan national hero assassinated by al-Qaeda in a suicide bombing on September 9, 2001, two days before the September 11 attacks that caused the US to intervene in Afghanistan.) His brother, Zia, became the first acting vice president of Afghanistan under Karzai. The film leads viewers to believe that the US supported the most "radical anti-western forces in Afghanistan," as Seigel himself stated in the discussion (rather than Massoud, his fighters, and the like), ridiculing Ronald Reagan for having compared freedom fighters we did support to George Washington, a reasonable comparison given Massoud's legendary status (he was called the Lion of the Panshir), his pro-Western stance, and the fact that he was assassinated immediately before 9-11 so as not be employed by the US in retaliation. Had he lived, he may have become the leader of Afghanistan after 9-11 (and so his brother become acting vice president instead, a man I briefly knew in the mid 80s). It seemed though that Seigel, while billed as an expert on Pakistan, either knows little about Afghanistan, while making it an important part of the film, or chose to simply distort in ways that suits his political leanings. The film also infers that America was to blame in the assassination of Bhutto, by selectively including the assertion of one protesting group in the aftermath of the assassination, as translated by Tariq Ali, a long time partisan against US foreign policy (the film does include comments by Condaleeza Rice, but not concerning these issues). Further, the film seems to prod viewers toward the ideological presumption that if only America would stop working with dictators, things would work out much more nicely in the world (hence the impressionable young man's question at the outset of the discussion), when, in fact, realistically, the world is full of dictators and it would be quite a trick to enlist their cooperation while insisting that they give up power (witness Mubarak in Egypt, a scenario that ended in disaster for American interests, or other dictators removed from power and then the utterly destabilized aftermath: Yugoslavia, Libya, etc). And so, I attended this film with two Muslim women (family members by marriage), hoping they would find in Benazir Bhutto a figure they could look to for inspiration, and I'm sure the film accomplished that to some degree, for it adequately chronicles her life, imprisonment, and heartbreaking trials, but it fails in other ways. Particularly telling was the producer's inclusion of his own weeping when being interviewed, as he recalled the tragic assassination. We certainly can't fault him for such feelings of grief, but to deliberately and conspicuously include such a scene in the film seems the height of self-indulgence, showing us his ability "to feel," when a more appropriate course of action, it seems, would been to have grieved in private, as opposed to having exploited that expression on film. It was really quite strange (although consistent with the "bleeding heart liberal" psychology) to see a producer presenting a film in which he, himself is choking on his tears, knowing that he is responsible for the production of the film, and so the word "self-indulgent comes to mind. Nor was he, apparently, able to separate his own political feelings from a film that should have been an homage to a truly great woman. That was why I attended, to behold such an homage, and so that two Muslim women living in the US could as well (and that was to some degree accomplished), not so that they would be induced to believing that America is always to blame.