Jean Loduca

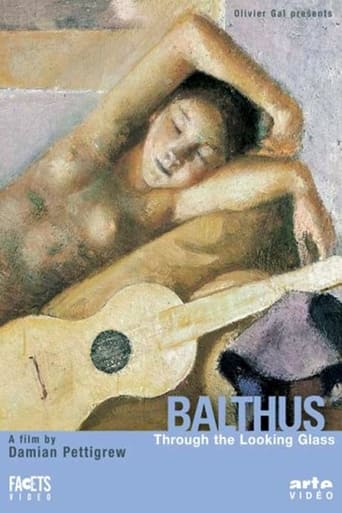

This rare portrait of Balthus offers genuine insight into a controversial artist's life and creative process. To begin with, the pedagogical interviews with distinguished art critics Jean Leymarie and Jean Clair are intercut with gorgeous images that guide you through the artist's perverse yet oddly magical world. Interviews with members of Balthus's family, in particular, his sons Stanislaus and Taddei, and his first wife Antoinette de Watteville, are beautifully subtle, highly revealing psychological studies in sadomasochism. Antoinette, for example, appears as an old woman with still vivid memories of her ex-husband's terrible temper, how she posed for him as a 16 year old beauty, and how they fled Paris when the Nazis invaded France during WW2. Stanislaus evokes the threat his father made of cutting off his thumbs if he ever took up painting while Taddei recalls never having been invited into his famous father's atelier. An intriguing visit to the Louvre finds Balthus quietly insulting his friends while studying a leopard by Pisanello, a new source of inspiration for his latest painting.François Rouan, French painter and Balthus disciple, describes in no uncertain terms the painter's obsession with adolescent girls that, while thoroughly hands off (Balthus is not a pedophile), remains invariably linked to time and the passing of physical beauty into decay and death. The essence of Balthus's art, Rouan argues, is sexual and driven by the need to capture the fleeting moment and preserve it on canvas in an activity properly doomed from the start.A convincing case is made for Balthus's flight from the madness that destroyed his close friend Antonin Artaud, and how the experience shaped his mature, more spiritually focused, work. In a haunting passage of genuine emotion, we catch a glimpse of the love between Balthus and his wife, Setsuko, as they contemplate one of the master's works in progress in his studio and later, at the Grand Chalet, when the artist reads a quotation from Horace as his wife traverses a narrow hallway into sunlight. The remarkable thing is that none of this comes off as faked or saccharine in director Pettigrew's hands and serves to underscore a controversial painter's simple humanity.Shot in Super 16 over 12 months in the Swiss Alps, we get to visit Balthus's studio where he explains his typical working day and watch in fascination as he goes through the gestures of monitoring the work in progress with the help of a hand mirror and long spells of nicotine-fueled meditations. His patient Japanese wife assists him in his work by grinding down and mixing the pigments with oil to create the artist's unique acrylic-free palette.What remains lingering in the mind, however, is the beauty of the film itself, the spellbinding, almost transcendent, moments of seasonal change from green summer mountains to wind-swept English moors to jaw-dropping Italian frescoes bathed in autumnal light to fog-heavy winter meadows that make up Balthus's intimate world.This rare cinematic quality allied to a subtle psychological intelligence and well-measured doses of art commentary is what makes 'Balthus Through the Looking Glass' a deeply satisfying film to watch and a world away from the flat-footed informational art doc.