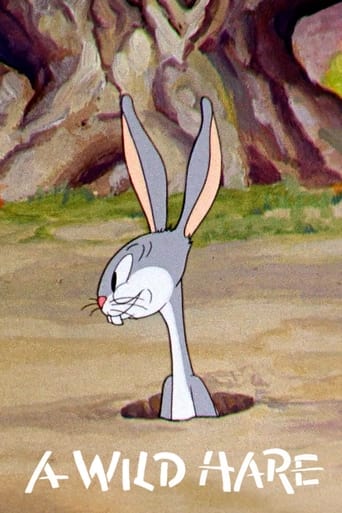

tavm

Okay, before I review the cartoon proper, I have to mention that there are two versions of this classic short. The original release version had the actual credits in the title sequence with the score of "I'm Just Wild About Harry" playing as the names of writer Rich Hogan and "supervisor" Fred Avery (a.k.a. Tex) appeared. It also had Bugs Bunny covering Elmer Fudd's eyes saying "Guess Who?" with the hunter saying-with "No" being answered each time-"Hedy Wamarr, Cawowe Wombard, Wosemawy Wane, Owivia De Haviwand?" The Blue Ribbin re-release just had the "Merrie Melodies" theme playing with just the title "The Wild Hare" printed at the end of that theme and "Bawbawa Stanwyck" replacing the late Lombard. Now while there are many familiar lines-like "Be vewy, vewy quiet. I'm hunting wabbits" and of course, "What's up, Doc?" and gags-like Bugs kissing Elmer and then Bugs pretending to die after Fudd shoots him and the hunter feeling sorry afterwards-I laughed just the same even after seeing this initial teaming of icons and their other cartoons over the years. While Arthur Q. Bryan's Elmer sounds the same here, Mel Blanc's Bugs seems a bit of a rougher Brooklyn/Bronx accent than we'd hear later on though I loved it when he shouts, "I AM A WABBIT!" in Fudd's ear! Despite being an Avery cartoon, A Wild Hare isn't as wild as many subsequent Bugs/Elmer or even Tex's later M-G-M shorts. Still, for anyone wanting to see where it all began, this film is very much worth a look.

Julia Arsenault (ja_kitty_71)

As I said, Bugs Bunny is one of my favorite Looney Tunes characters. But I do sometimes wonder what was his very first cartoon ever made? Now I have found out it is this short by Tex Avery, noted for his animated shorts at MGM, and I had watched it online at YouTube, and again at TCM's Cartoon Alley. I love the part when Bugs whispers in Elmer's ear. And I also love after his fake-death scene, Bugs gets up and kicks Elmer in the butt, and Elmer goes up like strength-tester and back down again. Then Bugs hands him a cigar which was the prize at that time. Overall, I thought it was a great "first appearance" short.

catradhtem

It is very hard to review "A Wild Hare" on its own solo merit after the sixty-plus years that followed and thus turned its central character into the biggest cartoon character ever. In comparison to the subsequent films that appeared until 1964, this very first official entry is tame but still a wonderful model for those that followed.Let's say this was 1940 and If I saw this cartoon for the first time ever with absolutely no knowledge of Bugs Bunny, I would say that "A Wild Hare" alone is a fine cartoon, in which the hunter becomes the heckled. The prey is a slick "wabbit" character that starts in on him at the very beginning, knocking on the wisping hunter's bald head to get his attention.It is no wonder that this cartoon is directed by Fred Avery, who only three years ago directed a similar cartoon called "Porky's Duck Hunt," in which Porky's prey evolved into the current Looney Tunes star Daffy Duck. Should we be keeping our eyes on this "wabbit?"

alice liddell

An early Bugs Bunny, not the most inventive - the animation is a little stilted, the usual flights of fantasy are rejected in favour of one hermetic setting, the Bugs persona is not quite as subversively developed as it would be. But there is much to enjoy. Elmer Fudd, shotgun ready, sets a trap for a rabbit by a gaping burrow. In a scene with wonderful Surrealist overtones, a hand emerges, and gropes for the carrot while the cocked rifle butt eyes eagerly.This is followed by a conventional scene of Bugs identity games, that would be used by Ionesco in over a decade for 'The Bald Prima Donna'. Taking mock-pity on an exasperated Fudd, Bugs allows him one shot at him, falls down and dies. Fudd's genuine grief is startling - surely it's natural in a rural environment for a hunter to shoot a rabbit - that it's a relief to see Bugs jump up and mock him, and not just to see him alive.Bugs continues here his very perceptive critique of Hollywood cliche and ideology, here satirising, among other things, the overextended costume-drama death scene (respectable cinema, remember!), and his histrionics are a lot more convincing than those of CAMILLE. The pastoral, vernal setting also mocks Emersonian Romantic rhetoric; the (literally) earthy Bugs, with his protean deconstruction, is joyfully at odds with long-winded transcendences of the self.