ashvinkurian

Watching this movie was quite an emotional experience for me. It made me realise what a truly brilliant man Gandhi was and the undeniable truth in his ideas. It also helped me appreciate how revolutionary these ideas were when they were first suggested, and how influential and relevant they are even today.The film is about three non-violent 'revolutions' that occurred this century - in India in the 30s, Black America in the late 50s and South Africa in the 80s. The makers of this film have done a good job of choosing to reduce the temporal scope of the documentaries, resulting in a detailed study of the actual logistics of civil disobedience. They have managed to obtain some amazing footage, in each of the three cases, that i had not seen before - such as the reactions of white store-owners in tennessee, and the riots in the townships of south africa.I had the pleasure of watching it on film, rather than on tv. If you are interested in watching it, it will be shown on PBS in (the summer? of) 2000. For exact dates, contact your local PBS affiliate.

perew

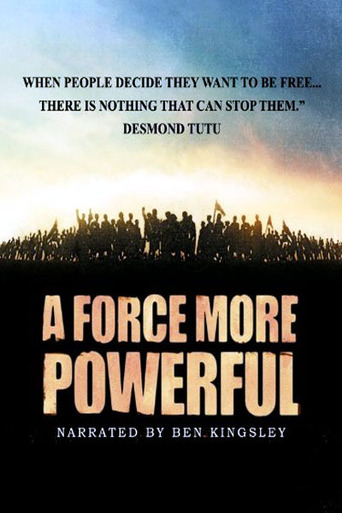

Waging moral combat against an immoral war is examined in a new documentary by York-Zimmerman Films. This long needed film explores not the wars of one nation against another, not even of a nation against itself, but the warfare of the ruling elite against those who make up the vital backbone and even rightful center of a society. In A Force More Powerful: A Century of Non-violent Combat, the methods successfully used to fight back are examined and shown to be carefully crafted and excellently executed.The film examines three conflicts where non-violent tactics achieved profound results. Serving as prologue to this tale is Mohandas K. Gandhi's struggle in South Africa. In the early 20th century, even before the repugnant apartheid laws, Indian citizens were treated no better than the native black population. It was during this struggle that Gandhi developed his philosophy of satyagraha, Sanskrit for "holding to truth". Based on the belief that both persecution and violence are wrong, Gandhi showed that by forcing the evil and harm to become visible in its most vile form, the oppressors would be compelled to concede to their opponents. This reductio ad absurdum approach proved to be the key to success in Gandhi's South Africa and elsewhere around the globe.Narrated by Ben Kingsley, who won both the Academy Award and Golden Globe for his 1982 performance as the title character in Gandhi, the film is told through news and documentary footage of the struggles described, plus short, tightly focused comments from those who were direct witnesses to or actual participants in the events. Only Kingsley's narrative provides any third party editorial on the history which is presented. Even then, it serves mostly to focus and frame; seldom to pontificate.The choice of Ben Kingsley as narrator is ironic. The son of an English mother and an Indian father, Kingsley's birthname was Krishna Bhanji. At the age of 19 Kingsley saw the Royal Shakespeare Company perform at Stratford-upon-Avon and decided to become an actor. His father suggested that if the young Krishna were to have a successful English stage career that he should take on an English name. Being good was not good enough. He had to be both good and fully, not half, English.For Gandhi, though, the choice was the opposite.Following the brief prologue, the movie moves into the first major section: Gandhi's struggle for Indian independence from British colonialism. The prologue's pictures of Gandhi show the Oxford educated barrister sporting a full head of hair and dressed in a morning coat. With the shift to Gandhi's native India all vestiges of Western appearance, save a pair of eyeglasses, are lost. Now with a shaven head, wearing a cotton shawl over a simple dhoti or breechclout and shod in plain sandals, Gandhi assumes the ascetic Eastern identity for which he is known. It is here that he becomes the Mahatma or "great soul".The methods used by Gandhi, and learned by others, are shown to be both simple and complex. A period of study revealed the oppressor's weaknesses. Points where economic and political pressure could be applied were identified. Absurd laws were found which could be flaunted to force the opponent to respond disproportionately. And, communication channels were opened so that the court of public opinion would rule in favor of the disenfranchised and so that media could show the kindness and gentleness of the oppressed and the violence of the oppressors.Once these points had been identified, then the troops needed to wage the non-violent conflict were trained. In the case of Nashville, many hours were spent in mock confrontations. Codes of dress and conduct were drilled into the participants. The non-combative combatants were required to have discipline and order and follow strict rules. They became an army waging a most unconventional form of warfare.The significance of openness in saytagraha is also carefully demonstrated. The confronted were given every chance to know where and when the skirmish would occur. There were no sneak attacks. The battle would take place in the open where all could see that truth, honor and justice belonged to one and only one side.James Lawson, a black Methodist minister in Nashville, Tennessee had studied satyagraha under Gandhi. The second section of A Force More Powerful, maps how he used this method to lead to the end of the segregation in that city in 1959. The racially segregated downtown lunch counters as the focal point of the protest. After the successes in Nashville, the leaders were able to take their skills elsewhere in the country and use them to great effect in the Civil Right movement.For the third and final section, the movie returns to South Africa to show the efforts of Mkhuseli Jack, a leader of the United Democratic Front(UDF), to end apartheid in his homeland. It is here that the failure of violent overthrow is most clearly seen against the successes of non-violent combat. This is especially striking in view of the extremely violent, militaristic and deadly response by the white minority Afrikaaner government and the "eye for eye" retribution and escalation of combat performed by the African National Congress (ANC).It is of no little importance that the film briefly, but clearly, puts South African President Nelson Mandela, then being held in prison for terrorism, in his place. While using Nelson Mandela's great visibility to their advantage, the UDF did not see Mandela's refusal to renounce violent overthrow of the Afrikaaner government and his continued support for the ANC as praiseworthy. The film shows that there is no mistake made. Mandela's imprisonment was his own fault and had he been willing to join the non-violent fight for freedom he would have been released years earlier.The events described by this film are historical fact. What is, apparently, new and well covered is the way in which the non-violent struggle shaped the overall confrontation, and in the end was the more powerful force.